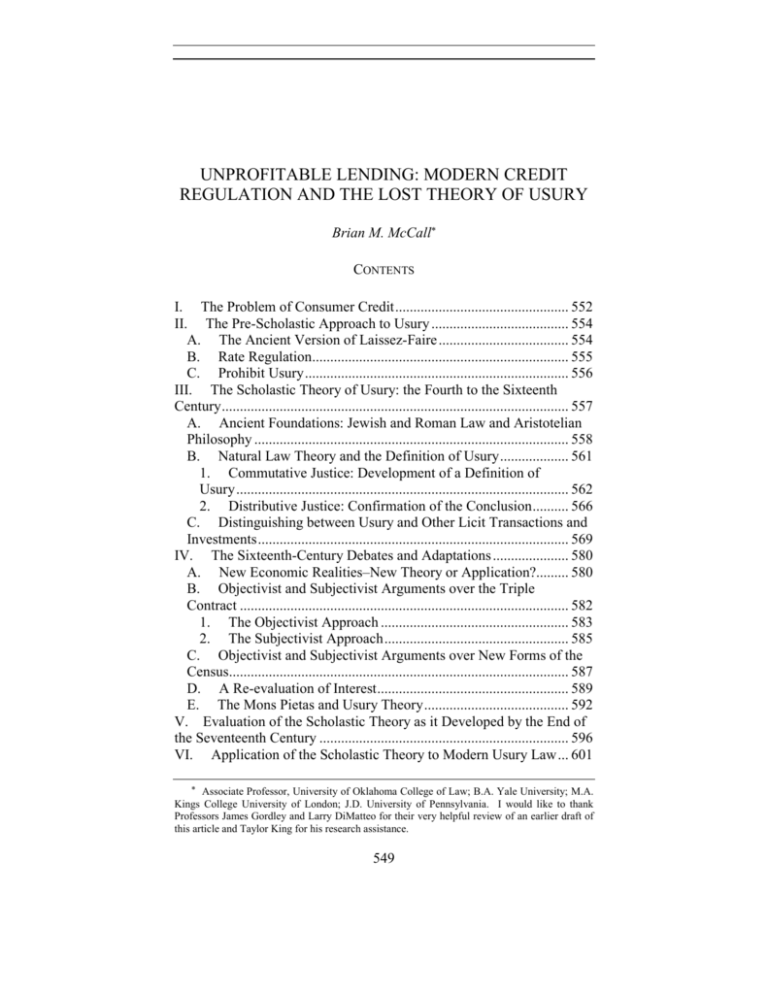

Unprofitable Lending: Modern Credit Regulation and the Lost

advertisement