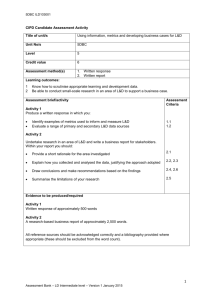

gcse examiners' reports

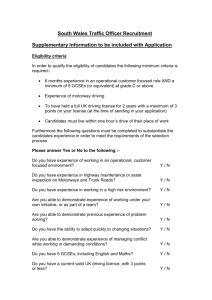

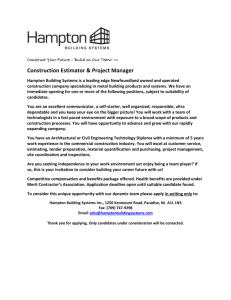

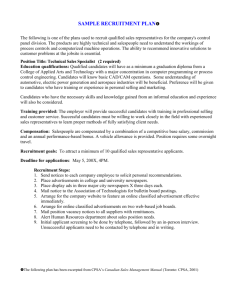

advertisement