On The ECONOMICS of VOLUNTEERING

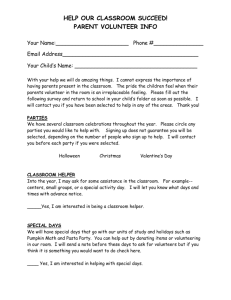

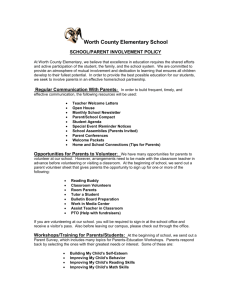

advertisement