Volunteering and Mandatory Community Service

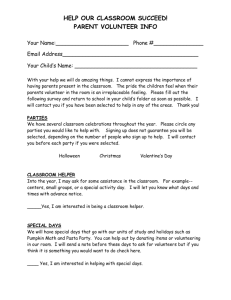

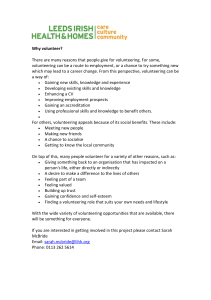

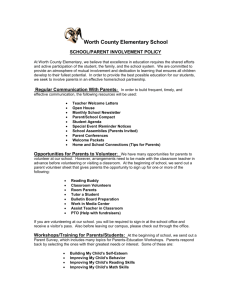

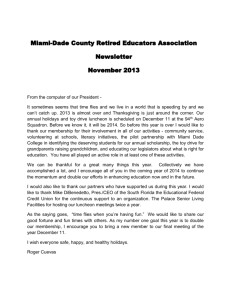

advertisement