Overview of Club Operations

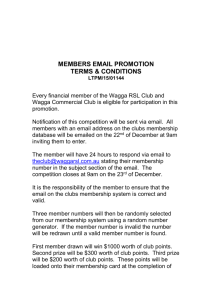

advertisement