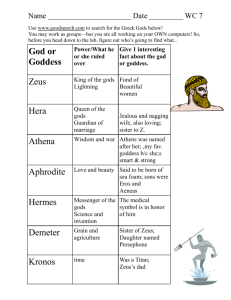

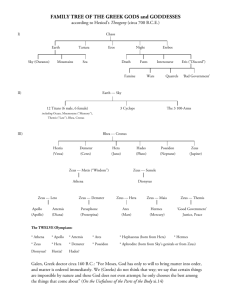

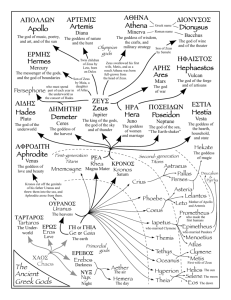

The Olympians - Clark University

advertisement