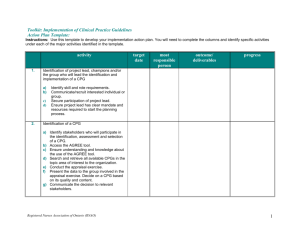

clinical practice guidelines

advertisement