designing the boundaries of the firm

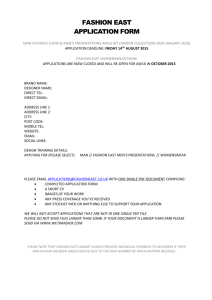

advertisement