The Impact of Politics on Language: The Cold War, Vietnam

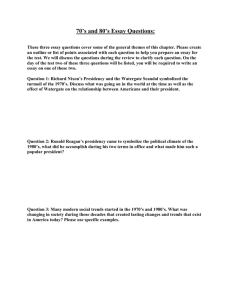

advertisement