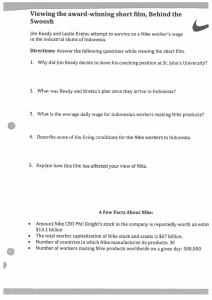

Nike in Asia – Just do it

advertisement

Nike in Asia – Just do it! This case, which is based on published sources, was prepared by John Hendry with the assistance of MBA student Toshiaki Fujikawa. It draws heavily on two earlier cases: P.M. Rosenzweig, “International sourcing in athletic footwear” (HBS 9394-1489) and T. Wheelen, M.H. Abdelsamad, S.E. Fieber and J.D.Smith, “Reebok International Ltd (1995): The Nike Challenge” from T.L.Wheelen & J.D. Hunger, Strategic Management. 6th edition. Addison Wesley, 1998. The case is intended to provide a basis for class discussion and not to illustrate either effective or ineffective handling of an administrative situation. Nike Inc. needs little introduction. With revenues of nearly $10 billion in 1998 and a dominant position in the worldwide athletic shoe and sports leisure wear industries it owns one of the world’s most famous brands and most instantly recognisable logos. In purely economic terms, the story of Oregon-based Nike since its creation by Philip Knight in the 1960s has been one of almost continuous success, but since 1991 the corporation has also attracted attention for another reason. This case reviews some of the criticisms that have been made of Nike on ethical grounds and the corporation’s responses to them, in the context of the competitive pressures of the industry in which it operates. Nike and the athletic footwear industry When Nike was founded in 1964 the athletic footwear industry was a relatively small, specialist industry with a pure sports orientation, dominated by the German companies Adidas and Puma. In the 1980s and 1990s, however, the industry has grown rapidly as, beginning in the USA and subsequently throughout the world sporting activities have become increasingly fashionable and sportswear, in particular the ubiquitous “trainer”, has come to dominate leisurewear fashions even for those not engaged in active sports. By the early 1990s, Nike had held the number one position in the American athletic footwear market for over a decade and held over 30% of that market. It was also firmly established as number one in the global market with a market share of over 20%. Both revenues and profits were growing steadily at between 20% and 30% per annum (see Exhibits 1 to 4 for financial and market share data). But while these results were very satisfactory there was no room for complacency. Nike’s lead over its main competitor, the Anglo-American company Reebok, was a very narrow one, and both Reebok and a resurgent Adidas were stronger than Nike John Hendry 2000 1 outside the USA, and especially in the economies of Western Europe that were expected to be critical for future market growth. While the public appetite for athletic footwear as leisure fashion continued to grow there was also the ever-present danger of a dramatic change in fashions back to the traditional leisure shoe, a change that could also be expected to hit Nike’s non-footwear products such as baseball caps and sweatshirts. The primary focus of competition in the modern athletic footwear industry is marketing, with the leading players spending around 10% of their revues to promote their brands through advertising and endorsements. Nike, Reebok and Adidas all follow classic differentiation strategies, seeking to sell their products on quality and image at a premium price rather than to compete with each other or with their smaller competitors on the basis of low prices. Their production costs are still significant, however, and minimising these costs has always been very important. (Exhibit 5 gives a typical cost breakdown.) Nike’s production strategy Neither Nike nor its main competitor Reebok manufacture their own shoes, both corporations relying on Far Eastern subcontractors. In the 1980s, most of the shoes were sourced from companies in Taiwan and South Korea, but as wages in both these countries rose sharply in the second half of the decade, rising two and a half times between 1986 and 1990, these companies came under strong pressure from Nike and Reebok to shift production to lower wage countries. By tying future, guaranteed orders to significant cost improvements they encouraged the companies to invest heavily in new plant in China and Indonesia. By 1990, Nike was already sourcing from six factories in Indonesia, four of which were owned by its established South Korean suppliers while the other two were locally owned. Together they employed 24,000 workers and accounted for 8% of Nike’s global volume. Over the next three years, the number of people employed overall in the South Korean and Taiwanese shoe industries fell dramatically (from nearly 500,000 to just 120,000 in South Korea). By 1992 the majority of Nike’s shoes (and the majority of Reebok’s too) were being sourced from South Korean owned factories in Indonesia and Taiwanese owned factories in China. Thailand, the Philippines and, later in the decade, Vietnam, were the other main sources of production. The main attraction of countries like Indonesia and China was their low labour costs, which were less than 10% of those in Taiwan and South Korea and around 4% of those in the USA (see Exhibit 6). Indonesia, which was to be the main focus of Nike’s critics, had a population of 180 million, a rapidly growing workforce and very high unemployment. Employment legislation was weak and the government, which was desperately keen to encourage foreign manufacturers, did not appear too worried about enforcing what laws there were. From an economic point of view, for a company such as Nike, it was heaven. Criticisms and responses It was not, however, heaven for the Indonesian people, and from 1991 onwards Nike came under repeated attack for what, it was claimed, were seriously unethical aspects of its John Hendry 2000 2 sourcing policy. The first criticisms came in two 1991 reports, one from the Indonesian Institut Teknology Bandung and the other from the Asian-American Free Labor Institute, which accused Nike’s subcontractors of violating child labour laws, failing to respect special work rules for women, forcing people to work overtime and paying less than the minimum wage, which at the equivalent of US$1 a day was itself not enough even to feed an individual. (Even after the minimum wage was raised to the equivalent of US$1.20 in 1992 it was reported that, at prevailing food prices, this could purchase only 70% of an individual’s minimum calorific needs.) The AAFLI report claimed that young women employees complained of an atmosphere of fear, with South Korean managers shouting at and threatening them. Nike responded to these criticisms in two ways. Externally, the corporation argued that the problems lay with its subcontractors, for whom it should not be held responsible. As the Nike general manager in Jakarta responded: “They are subcontractors: it’s not within our scope to investigate.” The Nike vice-president for Asia was similarly reported as saying that “we don’t know the first thing about manufacturing. We are marketers and designers”. Anyway, he added, regardless of the criticisms Nike was bringing great benefits to Indonesia: “We’ve come in here and given jobs to thousands of people who wouldn’t be working otherwise.” Internally, however, Nike drew up a Memorandum of Understanding (Exhibit 7) to act as the basis for its subcontractor and supplier relationships and protect it from future criticisms. This required subcontractors not only to comply with local legislation but also to maintain on file evidence of such compliance. It also required them to adhere to Nike’s own environmental and equal opportunities practices. The Memorandum of Understanding was drawn up in 1992 and adopted formally in 1993, but it did not protect the corporation from further criticism. A CBS report on a Nike subcontractor’s Indonesian factory in the summer of 1993 drew attention to continuing low wages and to a system in which women employees lived in on-site company barracks which they were only allowed to leave on Sundays, and then only with written management permission. This report sparked off a constant stream of criticism, which had barely subsided when, three years later in October 1996, another CBS program, this time on a Nike subcontractor’s factory in Vietnam, reported the use of physical violence on employees. “You have to meet the quota before you can go home”, said one woman, “[The supervisor] hit all 15 team leaders in turn from the first to the fifteenth.” Another added: “The physical pain didn’t last long, but the pain I feel in my heart will never disappear.” The 1996 CBS program led to a barrage of criticisms from the media and human rights groups, followed by boycott campaigns on college campuses and by consumer activist groups. The criticisms were applied generally, to all of Nike’s Asian subcontracted operations, and focused on six points. Low wages. Although Nike claimed that the median wage paid to employees in Indonesian factories was over double the legal minimum wage, human rights groups found that the majority of workers were paid at the minimum wage. Because of very high unemployment and the absence of a welfare system, people were prepared, even eager to work at this rate, but the fact John Hendry 2000 3 remained that it was insufficient to feed someone adequately, let alone to support a family or allow for any non-food purchases. Forced overtime. Researches into working conditions in factories repeatedly found that employees were forced to work exceptionally long hours (indeed this appears to have been the main explanation for the discrepancy between the wage level and the median take-home pay). Nike insisted that overtime was voluntary, but most employees could not survive without it and reports also suggested that people refusing to work overtime were punished. Working conditions. There were numerous reports of accidents and injuries, including respiratory and skin diseases resulting from the handling of chemicals, and machine accidents – mainly lost fingers – resulting from overtiredness. Abuse. One report said that when an inspector from Nike arrived at a factory to inspect the product he discovered that an incorrect colour was being used on the outsoles. He reprimanded the South Korean manager, who in turn lined up six workers, blamed them for the mistake, and hit each one on the head with an outsole. Harassment. Media reports suggested that when workers demonstrated against their wages or conditions they were threatened not only by their company but by government forces as well. Child labour. Reports drew attention to the fact that the minimum working age in Indonesia was only 14, and in some other countries children as young as 12 were employed in the manufacture of Nike apparel and accessories. Nike’s reputation was not helped by the leak, in November 1997, of an internal audit report of a subcontractor’s factory in Vietnam, commissioned by Nike from Ernst & Young. This disclosed that the factory lacked adequate safety equipment and training; exposed employees to hazardous chemicals and dangerous levels of noise, heat and dust; and encouraged excess overtime, with some employees working 700 hours of overtime a year as compared to the official Vietnamese national limit of 200 hours. As before, Nike responded to its critics in two ways. At first, it tried to defend its position. “Why … are we the sole target of all this interest?” asked a company representative in 1993. “In Portland (Oregon) alone there are no less than four companies subcontracting for athletic shoes and apparel in Indonesia, China and Korea.” “We don’t pay anybody at the factories”, complained another representative in 1994, “and we don’t set policy within the factories; it is their business to run.” A company document from the same year stressed the positive side: As a player in Indonesia’s economy, Nike is part of a plan that has succeeded in increasing per capita income ten-fold since 1970 while decreasing those John Hendry 2000 4 living in poverty from 60 percent to 15 percent. In 1994 athletic footwear manufacturing will generate more than US$1,500 million in export sales for Indonesia, 375 times the sales of 1998. In 1995 a company representative made the same point in more human terms: The overwhelming share of workers in our subcontract factories [in Indonesia] have had a positive experience. … It is clear to them that manufacturing jobs pay a steady wage, and offer the kinds of benefits that are prized in a country where half the work force is still earning a subsistence income on a farm, often with neither running water nor electricity. … In a country where the population is increasing 2.5 million a year, with 40 percent unemployment, it is better to work in a shoe factory than not to have a job. Unfortunately for Nike, not everyone agreed with these assessments. Poverty statistics depend on how you measure poverty, and when a country is aggressively industrialising and destroying its natural resources they can be misleading. Is it better to be a subsistence farmer, with zero recorded economic income (and so officially in poverty) but enough food and shelter for a family to get by, or to be employed in a city at a wage that comes above the official poverty level but is still not enough to feed or house a family? Nike, in common with the rest of corporate America, took one view, but its critics took another, and far from reassuring them the company’s statements seemed to some to cast increasing doubts on its honesty and integrity. The criticisms refused to die down and by 1997-98 the company was being presented (in a Doonesbury cartoon strip, for example) as intentionally misrepresenting the position and viewpoints of the workers in its subcontractors’ factories. In May 1998, after almost a decade of constant criticism, Nike finally tried a different response and announced a six-point plan (Exhibit 8) to significantly improve working conditions in its suppliers’ Asian factories, together by a new Code of Conduct formulated the previous year (Exhibit 9). It pledged among other things to raise the minimum age requirements in the factories to 18 for footwear factories and 16 for other light manufacturing (the critical difference being that shoe factories use noxious chemicals), and to enforce this strictly; to significantly improve environmental and health and safety standards and training requirements; to require subcontractors to offer free after-hours education to employees; and to work with NGOs towards a system of independent monitoring and certification of labour practices. A corporate or industry problem? One of Nike’s constant complaints was that it was being unfairly singled out for criticism, and in this context it is worth looking very briefly at the fate of its main competitor Reebok. As already noted, Reebok’s production strategy was very similar to Nike’s, and as both corporations’ subcontractors moved into Indonesia at the beginning of the decade Reebok was exposed to very much the same kinds of criticism as Nike. As the decade wore on, however, the criticism and consumer boycott attempts focused increasingly on Nike. Reebok, while not altogether immune from criticism, escaped relatively lightly. In part, this seems to John Hendry 2000 5 have reflected different corporate cultures. Whereas the Nike approach was always aggressively commercial and success-oriented, the Reebok culture was much more relaxed – in the mid-1990s, indeed, it was too relaxed for its institutional shareholders, who were demanding that it take a much harder, less tolerant, more Nike-like approach. For Reebok, economic performance was important but it was not everything, and the company had, in particular, a longstanding concern with and commitment to human rights. It already had, by 1990, a formal human rights policy, and in response to the criticisms of the following year it developed this into a set of human rights production standards (Exhibit 10). These were announced in May 1993, just a couple of months before the damning CBS report on Nike and they called not only for high standards of employment conditions in its subcontractor factories but also for the routine auditing of those conditions. John Hendry 2000 6 Exhibit 1: Nike Inc financial data (in US$millions) (Source: 1998 Annual Report) 1998 $ 1997 $ 1996 $ 1995 $ 1994 $ 1993 $ 1992 $ 1991 $ 1990 $ 9,553.1 3,487.6 36.5% 129.9 399.6 1.38 1.35 288.7 295.0 0.46 517.5 9,186.5 3,688.5 40.1% 795.8 2.76 1.88 288.4 297.0 0.38 323.1 6,470.6 2,563.9 39.6% 553.2 1.93 1.36 386.6 293.6 0.29 339.7 4,760.8 1,895.6 39.8% 399.7 1.38 0.99 289.6 294.0 0.24 254.9 3,789.7 1,488.2 39.3% 298.8 1.00 1.18 298.6 301.8 0.20 576.5 3,931.0 1,544.0 39.3% 365.0 1.20 1.07 302.9 308.3 0.19 265.3 3,405.2 1,316.1 38.7% 329.2 1.09 1.07 301.7 306.4 0.15 435.8 3.003.6 1,153.1 38.4% 287.0 0.96 0.94 300.4 304.3 0.13 11.1 2,235.2 851.1 38.1% 243.0 0.81 0.80 299.1 302.7 0.10 127.1 108.6 1,396.6 1,828.8 5,397.4 379.4 0.3 3261.6 46.0 13,201.1 445.4 1,338.6 1,964.0 5,361.2 296.0 0.3 3155.9 57.5 16,633.0 262.1 931.2 1,259.9 3,951.6 9.6 0.3 2431.4 50.2 14,416.8 216.1 629.7 938.4 3,142.7 10.6 0.3 1964.7 19.7 5,635.2 518.8 470.0 1,208.4 2,373.8 12.4 0.3 1740.9 14.8 4,318.8 291.3 593.0 1,165.2 2,186.3 15.0 0.3 1642.8 18.1 5,499.3 260.1 471.2 964.3 1,871.7 69.5 0.3 1328.5 14.5 4,379.6 119.8 586.6 662.6 1,707.2 30.0 0.3 1029.6 9.9 13,201.1 90.4 309.5 561.6 1,093.4 25.9 0.3 781.0 9.8 13,201.1 12.5% 7.4% 4.4 2.1 34.1 28.5% 17.1% 4.8 2.1 21.5 25.2% 15.6% 5.0 1.9 26.6 21.6% 14.5% 5.2 1.8 14.5 17.7% 13.1% 4.3 3.2 14.9 24.5% 18.0% 4.5 3.6 15.3 27.9% 18.4% 3.9 3.3 13.5 31.7% 20.5% 4.1 2.1 10.5 36.3% 25.3% 5.2 3.1 12.2 GEOGRAPHIC REVENUES United States 5,452.5 5,529.1 3,964.7 2,997.9 2,432.7 2,528.8 2,270.9 2,141.5 1,755.5 Europe Asia/Pacific Canada, Latin America and other Total Revenues 2,143.7 1,255.7 701.2 9,553.1 1,833.7 1,245.2 578.5 9,186.5 1,334.3 735.1 436.5 6,470.6 980.4 515.6 266.9 4,760.8 927.3 283.4 146.3 3,789.7 1,085.7 178.2 138.3 3,931.0 919.8 75.7 138.8 3,405.2 664.7 56.2 141.2 3,003.6 334.3 29.3 116.1 2,235.2 YEAR ENDED MAY 31 Revenue Gross margin Gross margin % Restructuring charge Net income Basic earnings per common share Diluted earnings per common share Average common shares outstanding Diluted avg. common shares outstanding Declared dividends per common share Cash flow from operations AT MAY 31 Cash and equivalents Inventories Working capital Total assets Long-term debt Redeemable Preferred Stock Common shareholders’ equity Year-end stock price Market capitalization FINANCIAL RATIOS Return on equity Return on assets Inventory turns Current ratio at May 31 Price/earnings ratio at May 31 (Diluted) John Hendry 2000 7 Exhibit 2: Comparative data on US-based competitors in the athletic shoe industry (Source: Value Line, May 26, 1995, as presented in T. Wheelen, M.H. Abdelsamad, S.E. Fieber and J.D.Smith, “Reebok International Ltd (1995): The Nike Challenge” from T.L.Wheelen & J.D. Hunger, Strategic Management. 6th edition. Addison Wesley, 1998.) A. REVENUES (Millions of dollars) Estimated Company 1996 1995 Nike $ 5,000 $4,525 Reebok 3,750 3,500 Stride Rite 600 500 L.A. Gear 460 440 1994 $3,789.7 3,280.4 523.9 416.0 1993 $3,931.0 2,893.9 582.9 398.4 Actual 1992 $3,405.2 3,022.6 585.9 430.2 1991 $3,003.6 2,734.5 574.4 618.1 1990 $2,235.2 2,159.2 516.0 902.2 B. NET PROFITS (Millions of dollars) Estimated Company 1996 1995 Nike $ 420 $ 375 Reebok 255 245 Stride Rite 40 30 L.A. Gear (0.5) (5.0) 1994 $ 298.80 254.50 19.80 (22.2) 1993 $ 365.0 230.5 60.3 (32.5) Actual 1992 $ 329.2 232.3 72.9 (71.9) 1991 $ 287.1 234.7 66.0 (45.0) 1990 $ 243.0 176.6 55.5 31.3 1994 15.3% 13.9 7.7 Loss 1993 17.4% 14.8 17.1 Loss Actual 1992 17.7% 14.4 20.8 Loss 1991 17.4% 16.3 19.1 Loss 1990 18.5% 15.5 18.1 31.3 1994 1993 Actual 1992 1991 1990 C. OPERATING PROFIT MARGIN (%) Estimated Company Nike Reebok Stride Rite L.A. Gear D. 1996 16.0% 13.0 12.0 3.0 1995 16.0% 13.0 11.0 2.0 NET PROFIT MARGINS (%) Estimated Company Nike Reebok Stride Rite L.A. Gear 1996 8.4% 6.9 6.5 Loss John Hendry 2000 1995 8.3% 7.0 5.4 Loss 7.9% 7.8 3.8 Loss 9.3% 8.0 10.3 Loss 8 9.7% 7.7 12.4 Loss 9.6% 8.6 11.5 Loss 10.9% 8.2 10.8 3.5 Exhibit 3: US and global market shares in the athletic footwear industry, 1993/94 (Source: K.Labich, “Nike vs. Reebok”, Fortune, September 18, 1995, p.98, reprinted in T. Wheelen, M.H. Abdelsamad, S.E. Fieber and J.D.Smith, “Reebok International Ltd (1995): The Nike Challenge” from T.L.Wheelen & J.D. Hunger, Strategic Management. 6th edition. Addison Wesley, 1998.) Nike Reebok Adidas L.A.Gear Fila Keds Converse Asics Puma Other John Hendry 2000 U.S Market Share 1994 Global market Share 1993 29.7% 21.3% 5.1% 4.8% 4.7% 4.6% 4.6% 3.4% 24.1% 19.1% 10.0% 3.3% 2.6% 3.8% 4.0% 5.1% 5.0% 23.1% 21.8% 9 Exhibit 4: US and European athletic footwear market shares, 1990-94 (Source: Business Week, March 13, 1995, p.71, as presented in P.M. Rosenzweig, “International sourcing in athletic footwear” (HBS 9-394-1489) and Nike and Reebok annual reports.) 1990 USA Nike Reebok Adidas L.A.Gear Fila Keds Converse 29% 21 1991 29% 23 1992 30% 24 18 25 12 Nike Reebok Adidas Nike Reebok Adidas John Hendry 2000 11 12 16 10 1994 27 17 27 1993 14 20 14 1992 Italy 28 21 28 20 13 38 12 19 11 1994 1993 1992 Spain 1994 18 34 11 26 24 27 16 11 40 29.7% 21.3 5.1 4.8 4.7 4.6 4.6 1993 1992 Germany Nike Reebok Adidas 21 30 10 22 19 28 1994 1993 1992 France Nike Reebok Adidas 31.7% 20.6 3.1 4.7 4.0 5.8 4.3 1992 UK Nike Reebok Adidas 1993 1994 17 22 13 1993 14 15 17 1994 18 16 15 Exhibit 5: Typical cost breakdown of a pair of premium athletic shoes (Nike “Air Pegasus”) in US$ (Source: Washington Post, 1995) Labour Materials Rent, equipment Supplier’s profit 2.75 9.00 3.00 1.75 Duties and shipping 3.50 Cost to Nike John Hendry 2000 20.00 Cost to Nike R&D Promotion Sales, admin., distribution Nike Operating profit Cost to retailer 11 20.00 0.25 4.00 5.00 Cost to retailer Rent Personnel Other costs 35.50 9.00 9.50 7.00 6.25 Retailer’s profit 9.00 35.50 Cost to consumer 70.00 Exhibit 6: Hourly labour costs for production workers in textile and apparel industries, 1993 (Source: P.M. Rosenzweig, “International sourcing in athletic footwear” (HBS 9-394-1489)) Normal Equivalent Hourly Labour Days Worked – Cost – Apparel Textile (in U.S. dollars) (per operator per year) Country Hourly Labour Cost – Textile (in U.S. dollars) North America: United States Canada Mexico 11.61 13.44 2.93 8.13 9.14 1.08 241 237 286 Europe: Denmark France Germany Greece Ireland Netherlands 21.32 16.49 20.50 7.13 9.18 20.82 17.29 14.84 17.22 5.85 7.44 15.41 226 233 232 231 243 207 0.36 3.85 0.56 0.43 23.65 3.66 1.18 0.78 3.56 5.76 1.04 0.37 0.25 3.85 0.27 0.28 10.64 2.71 0.77 0.53 3.06 4.61 0.71 0.26 306 294 289 297 261 312 261 288 284 291 341 287 Asia: China (PRC) Hong Kong India Indonesia Japan South Korea Malaysia Philippines Singapore Taiwan Thailand Vietnam John Hendry 2000 12 Exhibit 7: Nike Memorandum of Understanding, 1993 (Source: Company document, reproduced in P.M. Rosenzweig, “International sourcing in athletic footwear” (HBS 9-394-1489)) 1. Government Regulation of Business (Subcontractor/supplier) certifies compliance with all applicable local labor government regulations regarding minimum wage, overtime, child labor laws, provisions for pregnancy, menstrual leave, provisions for vacations and holidays, and mandatory retirement benefits. 2. Safety and Health (Subcontractor/supplier) certifies compliance with all applicable local government regulations regarding occupational health and safety. 3. Worker Insurance (Subcontractor/supplier) certifies compliance with all applicable laws providing health insurance, life insurance, and worker’s compensation. 4. Forced Labor (Subcontractor/supplier) certifies that it and its suppliers and contractors do not use any form of forced labor – prison or otherwise. 5. Environment (Subcontractor/supplier) certifies compliance with all applicable local environmental regulations and adheres to Nike’s own broader environmental practices, including the prohibition of the use of chloro-fluoro-carbons (CFCs), the release of which could contribute to depletion of the earth’s ozone layer. 6. Equal Opportunity (Subcontractor/supplier) certifies that it does not discriminate in hiring, salary, benefits, advancement, termination, or retirement on the basis of gender, race, religion, age, sexual orientation or ethnic origin. 7. Documentation and Inspection (Subcontractor/supplier) agrees to maintain on file such documentation as may be needed to demonstrate compliance with the certifications in this Memorandum of Understanding and further agrees to make these documents available for Nike’s inspection upon request. John Hendry 2000 13 Exhibit 8: Nike action plan, 1998: Extract from Annual Report (Source: 1998 Annual Report) CORPORATE RESPONSIBILITY We thought now might be a good time to talk about corporate responsibility, here in the back of the book, last but certainly not least. Some of this information may surprise the most ardent Nike observer. A good reason to relay a few facts, some big and some small, about what we do off the field. Nike has consolidated the efforts of the Community Affairs, Environmental Action Team and Labor Practices groups into the Corporate Responsibility Division. This combined focus increases Nike’s effectiveness in the implementation of practices and investment in programs that will bring increased value to our shareholders, business partners, customers, employees and the communities where we do business. At Nike, corporate responsibility is defined by a sense of community, a regard for the environment and a commitment to integrity and diversity for our employees and the contract workers who make our product. To enhance the communities where Nike employees live and work, Nike Global Community Affairs supports programs that promote empowerment through a balance of sports, education and enterprise. All businesses depend on the earth for resources. At Nike, we are addressing the challenge of environmental sustainability through comprehensive product design, materials sourcing and manufacturing initiatives. Nike’s partnership with its employees and contract workers is critical to our business success. Two fundamental concepts guide Nike’s labor practices: best practices and continuous improvement. RESPONSIBLE LABOR PRACTICES On May 12, 1998, Phil Knight announced six new initiatives to improve factory working conditions and increase opportunities for people who manufacture Nike products. They are: Expanding Independent Monitoring: working with NGO (non-governmental organization) participation, Nike will initially focus on Vietnam, Indonesia and China. The ultimate goal is to establish a global system of independent certification of the company’s labor practices, much the same way financial information in this annual report is certified. Raising Minimum Age Requirements: Nike has increased the minimum age of footwear factory workers to 18 and the minimum age for all other light manufacturing workers (apparel, accessories, equipment) to 16. There is no tolerance for exception. Strengthening Environmental, Health and Safety Standards: Nike launched the Environmental, Health and Safety Management System (EHSMS) in June of ’98. The program, developed with two consultant groups (The Guantlett Group and Environmental Resources Management), will provide every factory where Nike footwear is made the tools and training to effectively manage and ensure continuous improvement throughout their environmental, health and safety programs. The program helps each factory develop a fully functioning EHSMS by June 2001. John Hendry 2000 14 KEY ENVIRONMENTAL, HEALTH AND SAFETY INITIATIVES: a) b) Indoor air testing of all footwear factories, and the monitoring of any necessary corrective measures to bring air quality to OSHA levels. Accelerated replacement of petroleum-based, organic solvents with safer water-based compounds. In an average month, nine of ten Nike shoes are made with water-based adhesives, with parallel substitutions underway for primers, degreasers and cleaners used in traditional footwear production. Expanded Worker Education: The Jobs + Education program offers footwear factory workers educational opportunities, such as middle school and high school equivalency courses. The classes will be free and scheduled during non-work hours. Factory participation is voluntary, but by 2002 Nike will order only from footwear factories that offer some form of after-hours education. Increasing Support of the Micro-enterprise Loan Program: The Jobs + Micro-enterprise Program will provide loans to women to create small businesses. Building on a successful program already responsible for 1000 loans in Vietnam, Nike will expand the program to reach an equal number of families in Indonesia, Thailand and Pakistan. Building understanding: Through the Rising Tides program. Nike is providing research grants and logistical support to universities and colleges to expand the academic body of knowledge on corporate responsibility, contract manufacturing and development issues involving Nike and other companies. Nike will also convene a series of open forums to foster dialogue with factory workers and partners, academics, NGOs and others interested in these issues. We are serious about these initiatives. We recognise that there is no finish line. Our goal is continuous improvement. Based on our new initiatives, we have amended and are enforcing the Nike Code of Conduct that directs our factory partners accordingly. Nike will sever its business relationship with any manufacturer refusing to meet these standards or exhibiting a pattern of violations. In the last year, Nike has terminated business with eight factories in four countries for not meeting our Code of Conduct requirements. John Hendry 2000 15 Exhibit 9: Nike Code of Conduct, 1997 (Source: Company document) NIKE Inc. was founded on a handshake. Implicit in that act was the determination that we would build our business with all of our partners based on trust, teamwork, honesty and mutual respect. We expect all of our business partners to operate on the same principles. At the core of the NIKE corporate ethic is the belief that we are a company comprised of many different kinds of people, appreciating individual diversity, and dedicated to equal opportunity for each individual. NIKE designs, manufactures and markets products for sports and fitness consumers. At every step in that process, we are driven to do not only what is required, but what is expected of a leader. We expect our business partners to do the same. Specifically, NIKE seeks partners that share our commitment to the promotion of best practices and continuous improvement in: 1. Occupational health and safety, compensation, hours of work and benefits. 2. Minimising our impact on the environment. 3. Management practices that recognise the dignity of the individual, the rights of free association and collective bargaining, and the right to a workplace free of harassment, abuse or corporal punishment. 4. The principle that decisions on hiring, salary, benefits, advancement, termination or retirement are based solely on the ability of an individual to do the job. Wherever NIKE operates around the globe, we are guided by this Code of Conduct. We bind our business partners to these principles. While these principles establish the spirit of our partnerships, we also bind these partners to specific standards of conduct. These are set forth below: 1. Forced Labour. (Contractor) certifies that it does not use any forced labour – prison, indentured, bonded or otherwise. 2. Child Labour. (Contractor) certifies it does not employ any person under the minimum age established by local law, or the age at which compulsory schooling has ended, whichever is greater, but in no case under the age of 14. 3. Compensation. (Contractor) certifies that it pays at least the minimum total compensation required by local law, including all mandated wages, allowances and benefits. 4. Benefits. (Contractor) certifies that it complies with all provisions for legally mandated benefits, including but not limited to housing; meals; transportation and other allowances; health care; child care; sick leave; emergency leave; pregnancy and menstrual leave; vacation, religious bereavement and holiday leave; and contributions for social security, life, health, worker’s compensation and other insurance. 5. Hours of Work/Overtime. (Contractor) certifies that it complies with legally mandated work hours; uses overtime only when employees are fully compensated according to local law; informs the employee at the time of hiring if mandatory overtime is a condition of employment; and, on a regularly scheduled basis, provides one day off in seven, and requires no more than 60 hours of work per week, or complies with local limits if they are lower. 6. Health and Safety. (Contractor) certifies that it has written health and safety guidelines, including those applying to employee residential facilities, where applicable; and that it has agreed in writing to comply with NIKE’s factory/vendor health and safety standards. 7. Environment. (Contractor) certifies that it complies with applicable country environmental regulations; and that it has agreed in writing to comply with NIKE’s specific vendor/factory John Hendry 2000 16 environmental policies and procedures, which are based on the concept of continuous improvement in processes and programs to reduce the impact on the environment. Documentation and Inspection (Contractor) agrees to maintain on file such documentation as may be needed to demonstrate compliance with this Code of Conduct and further agrees to make these documents available for NIKE or its designated auditor’s inspection upon request. Exhibit 10: Reebok Human Rights Production Standards, 1993 (Source: Company document, reproduced in P.M. Rosenzweig, “International sourcing in athletic footwear” (HBS 9-394-1489)) A Commitment to Human Rights Reebok’s devotion to human rights worldwide is a hallmark of our corporate culture. As a corporation in an ever-more global economy we will not be indifferent to the standards of our business partners around the world. We believe that the incorporation of internationally recognized human rights standards into our business practice improves worker morale and results in a higher quality working environment and higher quality products. In developing this policy, we have sought to use standards that are fair, that are appropriate to diverse cultures and that encourage workers to take pride in their work. Non-discrimination Reebok will seek business partners that do not discriminate in hiring and employment practices on grounds of race, colour, national origin, gender, religion, or political or other opinion. Working Hours/Overtime Reebok will seek business partners who do not require more than 60 hour work weeks on a regularly scheduled basis, except for appropriately compensated overtime in compliance with local laws, as we will favor business partners who use 48 hour work weeks as their maximum normal requirements. Forced or Compulsory Labor Reebok will not work with business partners that use forced or other compulsory labor, including labor that is required as a means of political coercion or as a punishment for holding or for peacefully expressing political views, in the manufacture of its products. Reebok will not purchase materials that were produced by forced prison or other compulsory labor and will terminate business relationships with any sources found to utilize such labor. Fair Wages Reebok will seek business partners who share our commitment to the betterment of wage and benefit levels that address the basic needs of workers and their families so far as possible and appropriate in light of national practices and conditions. Reebok will not select business partners that pay less than the minimum wage required by local law or that pay less than prevailing local industry practices (whichever is higher). Child Labor Reebok will not work with business partners that use child labor. The term “child” generally refers to a person who is less than 14 years of age, or younger than the age for completing compulsory education if that age is higher than 14. In countries where the law defines “child” to include individuals who are older than 14, Reebok will apply that definition. John Hendry 2000 17 Freedom of Association Reebok will seek business partners that share its commitment to the right of employees to establish and join organizations of their own choosing. Reebok will seek to assure that no employee is penalized because of his or her non-violent exercise of that right. Reebok recognizes and respects the right of all employees to organize and bargain collectively. Safe and Healthy Work Environment Reebok will seek business partners that strive to assure employees a safe and healthy workplace and that do not expose workers to hazardous conditions. Application of Standards Reebok will apply the Reebok Human Rights Production Standards in our selection of business partners. Reebok will seek compliance with these standards by our contractors, subcontractors, suppliers, and other business partners. To assure proper implementation of this policy, Reebok will seek business partners that allow Reebok full knowledge of the production facilities used and will undertaker affirmative measures, such as on-site inspection of production facilities, to implement and monitor these standards. Reebok takes strong objection to the use of force to suppress any of these standards and will take any such actions into account when evaluating facility compliance with these standards. John Hendry 2000 18