Simon W. Bowmaker PhD thesis

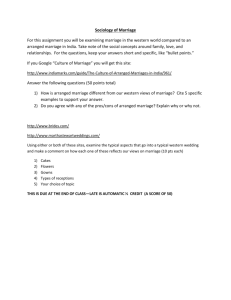

advertisement