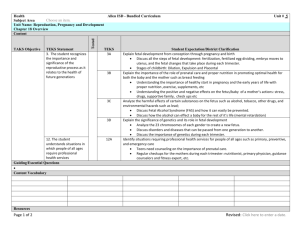

Nursing Care During Labor & Birth: Textbook Chapter

advertisement