Act 1 Act 2 Act 3 100 - Insight Publications

advertisement

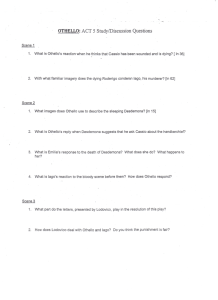

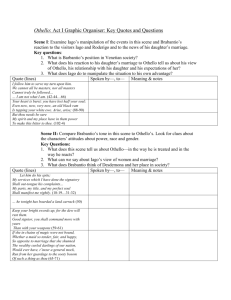

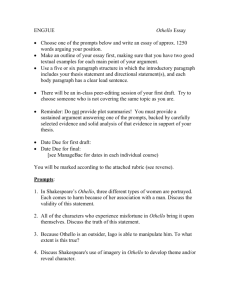

Contents About the authors vi Acknowledgements vi Introduction 1 Who was Shakespeare? 1 Jacobean England 3 A day at the theatre, London 1605 6 Dates and sources 8 Settings 8 Shakespeare’s language 10 Important vocabulary 17 The characters 18 Act summaries and activities 19 Act 1 23 Scene 1 Thieves! Thieves! Thieves! 23 Scene 2 Brabantio confronts Othello 34 Scene 3 (Part 1) Invasion 42 Scene 3 (Part 2) Iago’s monstrous birth 52 Act 2 64 Scene 1 (Part 1) Victory and arrivals 64 Scene 1 (Part 2) A jealousy so strong 75 Scene 2 Victory celebration 80 Scene 3 (Part 1) Cassio: drunk then demoted 82 Scene 3 (Part 2) A reputation lost and a plan devised 93 Act 3 100 Scene 1 Clowning around 100 Scene 2 A man of letters 104 Scene 3 (Part 1) Beware the green-eyed monster 106 Scene 3 (Part 2) Black vengeance 117 Scene 4 The handkerchief! 129 Contents Act 4 138 Scene 1 (Part 1) What Othello sees 138 Scene 1 (Part 2) Let her rot! 147 Scene 2 (Part 1) Strumpet! 154 Scene 2 (Part 2) Iago manipulates Roderigo 161 Scene 3 The Willow Song 166 Act 5 173 Scene 1 Murder in the dark 173 Scene 2 (Part 1) Put out the light 181 Scene 2 (Part 2) Iago’s darkness comes to light 192 General activities Oral presentations / performance 204 Questions for debate 205 Creative writing 205 Illustration 207 Questions for discussion 207 Essay questions 208 Appendices iv 204 209 To the teacher 209 A Shakespeare reading list 213 Vocabulary list 214 Image credits 217 Index 217 Contents Support materials History and criticism The Turkish threat 40 What did Othello look like? 63 Iago and the Devil 98 Shakespeare’s clowns 100 A soldier’s life 104 Women, marriage and society W 152 Othello as tragedy 202 Shakespeare’s themes & techniques Thinking about Othello and race 24 Introducing imagery: animal imagery 33 Thinking about conflict and antithesis 41 A word about soliloquies and asides 51 Introducing similes, metaphors and conceits 62 A word about pathetic fallacy and foreshadowing 74 Thinking about characters’ fatal flaws 79 Introducing dramatic irony 81 Annotating a soliloquy 92 A word about puns 103 A word about hyperbole 116 More about imagery 127 The deterioration of Othello’s language 146 Thinking about the conflict between illusion and reality 164 A word about repetition in Othello 171 Props as symbols in Othello 179 Performing Act 5 Scene 2 189 Othello’s final speech 191 v About the authors Shane Barnes BA Dip Ed is currently Deputy Principal at Craigmore Christian School, Adelaide. He has contributed several chapters to Great Ideas for English in the Senior Years (SAETA, 2001) and has presented at numerous SAETA and VATE workshops. Shane has been on marking and moderation panels for senior secondary level English and Tourism, and was nominated for a National Excellence in Teaching Award in 2007. Aidan Coleman BA Dip Ed teaches English at Cedar College, Adelaide. In 2004, he attended the prestigious Prince of Wales Shakespeare School at Stratford-upon-Avon, and in 2005 his poetry collection Avenues & Runways was short-listed for the New South Wales Premier’s Literary Award. Aidan has been awarded the ASG Community Merit Medal and a 2006 National Excellence In Teaching Award. Acknowledgements The authors wish to thank the following people: The South Australian English Teachers’ Association, for their ongoing and generous support. Dave McGillivray, who has appeared in many Shakespearean productions (including the State Theatre Company of South Australia), for many insights into the language and performability of Shakespeare. Abbie Thomas,Walford Anglican School for Girls, for her helpful comments and suggestions on the manuscript. Tess Coleman for proofreading. The staff at Insight Publications, especially Iris Breuer and Catherine Lewis, for their sound advice and willingness to listen to our ideas, as well as Robert Beardwood and Anni Dillon for their meticulous editing and intelligent suggestions. Our families, for their infinite patience, understanding, excitement and support. Insight Publications thanks the University of Birmingham for permission to reproduce the image of Abd el-Ouahed ben Messaoud ben Mohammed Anoun, Moorish Ambassador to Queen Elizabeth I, 1600. vi 00 ISP Othello prelims-4pp.indd 6 11/08/10 5:01 PM Dates and sources Shakespeare probably finished writing Othello in 1604. The first known registered performance was in November of that year before King James I at Whitehall. Othello was first published in 1622 as a Quarto (the Jacobean equivalent of a paperback today). One year later, it was included in a book that attempted to collect all of Shakespeare’s plays, a book we now refer to as the First Folio. In writing Othello, Shakespeare used ‘The Story of Disdemona of Venice and the Moorish Captain’ from a book of 110 short stories, published in 1565 by the Italian writer and professor of philosophy, Giovanni Battista Giraldi, commonly known as Cinthio. Shakespeare’s Othello shares many of the basic details of this story but is much more expansive and complex. In Cinthio’s story, the Moor (Othello in Shakespeare’s play) remains unnamed, as does the evil Ensign (Iago). In the original story, the Ensign is in love with Desdemona but Shakespeare makes Iago’s motivations far more ambiguous.The narratives of Cinthio and Shakespeare also differ greatly in their endings. In Cinthio’s story, the Ensign is caught after murdering Desdemona with the Moor’s consent. The story ends with the Ensign dying miserably and the Moor being sent into exile. Shakespeare’s resolution, however, sees Othello murdering Desdemona and then committing suicide. Settings Venice: Act 1 The opening act of Othello is set inVenice, a city in northern Italy consisting of a number of islands in the centre of a lagoon. Locals who were fleeing from barbarian invaders founded the city in the final years of the Roman Empire. As the Roman Empire dissolved, Italy broke up into a number of smaller states. During the Middle Ages, Venice became one of the most powerful and wealthy city-states in Italy. Because it was built in the middle of a lagoon,Venice’s streets were (and still are) canals and most Venetians moved about the city in long, narrow boats called gondolas. Not surprisingly, Venetian wealth and military power was due primarily to its large fleet of ships.Venice dominated trade between the Middle East and Europe, mainly in such luxury items as silks and spices. Through her naval power, Venice also added a number of islands, including Corfu, Crete and Cyprus, and significant areas of the Balkans to her territory in mainland Italy. The Venetians won their 8 I nsigh t Sh ake spea r e P l a ys greatest naval victory, over the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Lepanto, in 1571, shortly after the time in which Othello is set. Venice was a republic, which meant it was governed by the people rather than by a monarch. In reality, a rich aristocratic class held power and elected a Duke (called the Doge), often for life. After 1229, a Senate of 60 members assisted the Doge in running the Republic. We see the Senate in action in Act 1 Scene 3. Venetian law was considered to be fairly liberal or tolerant compared with other European nations. While the majority of Venetians were practising Roman Catholics, heretics (people who deviated from the orthodox faith) were rarely persecuted. In the minds of many Europeans, Venice was associated with luxury and decadence. It was already famous in Shakespeare’s time for its courtesans (prostitutes) and for massive spending on art and architecture. Venetians were quick to adopt the printing press and established the paperback format. By the late fifteenth century, Venice was a leader in European publishing. The signs of Venice’s decline were already apparent in Shakespeare’s day. The ongoing war with the Ottoman Empire proved very costly, and Venice’s problems were compounded by various international developments, including Christopher Columbus’ discovery of the Americas (1492) and Portugal’s discovery of a sea route to India (1498). These events, together with the rising naval power of Holland and England, broke Venice’s monopoly on trade. Venice’s decline continued and by the end of the seventeenth century, she was only a second-rate power. Cyprus: Acts 2–5 The final four acts of Othello are set in Cyprus, an island located in the Eastern Mediterranean, off the coast of Syria. The island generally experiences hot and dry summers, and productions of Othello usually emphasise this climate. Cyprus truly fits Cassio’s description as ‘this warlike isle’. Today, the mountainous landscape is still dominated by the imposing castles and forts left by the island’s various conquerors. Before the Venetians took charge in 1473, the island had been ruled by Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Greeks, Romans, Arabs, Byzantine Greeks and Crusaders. Othello is set at a time when the island was still ruled by the Venetians but was coming under increasing threat from the Ottoman Turks. The Turks conquered the island in 1570, when Shakespeare was six years old, with a force of 60 000 troops, and ruled in Cyprus until the mid-nineteenth century. The island is also associated with romantic love. In classical mythology, the goddess Aphrodite (Venus to the Romans) first came ashore on W i l l i a m S h a k e s p e a r e ’s O t h e l l o 9 Cyprus, after being born out of the sea-foam. Aphrodite was the goddess of beauty, love and sexual desire and, for this reason, Cyprus is often called the Island of Love. When Othello and Desdemona come ashore, they certainly are passionately in love, but Iago’s schemes will render the island’s title highly ironic. Shakespeare’s language Shakespeare wrote with an astonishing command of the English language. His lines are packed with puns, metaphors and ironies. He often uses words and phrases that sound strange to a modern reader, and some words have shifted in meaning since Shakespeare’s time. Sometimes he uses a different word-order from what you might be used to, and his characters often speak in poetry. Shakespeare’s language can, at times, be challenging, but the reward is in the challenge. Below are some tips on how to read the text and some of the main features to look out for. At this stage in your schooling, you should be relatively confident with terms like iambic pentameter and rhyming couplet. Even so, practise reading the text aloud and enjoy the sound of the language. Tips for reading It is vital not to pause at the end of a line if a thought or an idea continues on to the next line. The following example from Othello illustrates this point. Try reading it aloud, pausing at the end of each line. [Context: Iago plots to use Desdemona’s handkerchief as a way to poison Othello’s thoughts with jealousy.] IAGO I will in Cassio’s lodging lose this napkin, And let him find it. it.T Trifles light as air Are to the jealous confirmations strong As proofs of holy writ. writ.This This may do something. The Moor already changes with my poison; (Act 3 Scene 3) The most natural place in these lines to pause is where you see a punctuation mark such as a full stop (.), comma (,) or semi-colon (;). In this case, it is natural to pause at the full stops after ‘it’ and ‘writ’, at the comma after ‘napkin’ and at the semi-colon after ‘poison’. Read the lines again, this time pausing at punctuation marks rather than at the end of each line. You will notice that the lines flow much more smoothly now and that the meaning of the lines is clearer. Pause 10 I nsigh t Sh ake spea r e P l a ys for a little longer after ‘it’ and ‘writ’ than after ‘napkin’, as a comma does not require as long a breath as a full stop. The key point to remember is to pause in your reading only at punctuation marks, the same way you would when reading a novel. The dash In this version of Shakespeare’s Othello, the dash (–) is a specific punctuation mark. It is used to indicate interruptions to the flow of conversation in several ways. a Alternatingbetweenspeakingtoonecharacterandthen another [Context: Brabantio questions Roderigo as to the whereabouts of his daughter, Desdemona. Interrupting his questioning of Roderigo, Brabantio issues commands to his servants.] BRABANTIO … Wha Whatt said she to you? – Get more tapers; Raise all my kindred – Ar Aree they married, think you? (Act 1 Scene 1) b Becomingsidetrackedduringaconversation [Context:While Brabantio questions Roderigo as to the whereabouts of his daughter, his anxiety is indicated by the dashes in the text, showing that his thoughts are jumbled and interrupted.] BRABANTIO … Now, Roderigo, Wheree didst thou see her? – O unhappy girl! – Wher With the Moor, say’st thou? – Who would be a father! – How Ho w didst thou know ’twas she? – O she deceives me Past thought! … (Act 1 Scene 1) c Interruptinganothercharacter’sdialogue [Context: Desdemona tries to defend the reputation of Cassio before Othello, her husband. Othello’s interruptions, obsessing over Desdemona’s handkerchief, are indicated by dashes in the text.] DESDEMONA You’ll never meet a more sufficient man – OTHELLO The handkerchief! DESDEMONA I pray, talk me of Cassio – OTHELLO OTHELLO The handkerchief! (Act 3 Scene 4) The meaning of the dash (–) in the text is indicated by the context of the dialogue. In all cases in this edition of Othello, it signals an interruption of some sort. W i l l i a m S h a k e s p e a r e ’s O t h e l l o 11 Language features a Blankverseandiambicpentameter Most of Shakespeare’s plays are written in blank verse, which is unrhymed poetry written in a regular rhythm or meter known as iambic pentameter. The majority of Othello is written in blank verse, so we will start with this aspect in order to understand the rhythm of the text. For example: OTHELLO It gives me wonder great as my content To see you here before me. O my soul’s joy! (Act 2 Scene 1) Set out like a poem (verse) rather than a novel (prose), there is something else you might notice about these lines, besides the fact that they do not rhyme.Take a moment to read them aloud. Can you hear the rhythm in the words? Read the lines aloud once more. Can you hear the regular heartbeat repeating itself in each line? te-DUM, te-DUM, te-DUM, te-DUM, te-DUM ... Shakespeare generally uses ten beats per line, divided into what are called iambs. Each iamb contains one unstressed beat and one stressed beat (te-DUM). As each line has five iambs, this forms the rhythm called iambic pentameter (‘penta’ relates to a group of five, as in pentagon, which is a five-sided shape). This pattern is made clearer below, where the CAPITALISED letters are a stressed or strong beat.They should be emphasised a little more than the weaker beats: IAGO I’ll POUR this PEST-i-LENCE in-TO his EAR. (Act 2 Scene 3) Not only does Shakespeare’s iambic pentameter (five te-DUMs per line) work across words (‘his EAR’, as written above) and within words (as in ‘PEST-i-LENCE’ and ‘in-TO’ above), but also across speakers: OTHELLO DESDEMONA O my fair warrior! My My dear Othello! (Act 2 Scene 1) Shakespeare emphasises the bond between Othello and Desdemona by having Desdemona complete Othello’s line of iambic pentameter.This is shown in the text by indenting Desdemona’s lines. Whoever reads the part of Desdemona in this case should speak immediately after Othello to complete the rhythm of the line. In this way, the heart of the play does not stop beating. You will not necessarily be able to pick this rhythm straight away, but the more you read Shakespeare, the more you will develop a feel for blank verse, and especially for the all-important iambic pentameter. 12 I nsigh t Sh ake spea r e P l a ys Having said this, the rhythm is quite irregular at times in Othello, especially in comparison to Shakespeare’s earlier plays such as Romeo and Juliet and Richard III III. b Rhyme Despite the importance of blank verse (unrhymed iambic pentameter) in Shakespeare’s plays, some lines in Othello are actually written in rhyming verse. There are two different forms of rhyming verse used throughout the play. i Rhymingcouplets IAGO I have’t! It is engendered! Hell and night Must bring this monstrous birth to the world’s light. (Act 1 Scene 3) Sometimes a rhyming couplet (two consecutive lines that rhyme) helped the audience to know it was the end of the scene, and that they could fidget a little. It might also have been a cue to the actors that they were soon due on stage for the next scene. Structurally, it ties up a speech neatly and makes a point memorable, as in the example above. Note, too, that the rhyming couplet is still in iambic pentameter. At other times, Shakespeare uses rhyming couplets to signal a shift in tone in the midst of a scene; this is particularly notable in Othello. By way of illustration, when Brabantio reports Othello to the Duke for supposedly abusing Desdemona, the tension of the scene is relaxed when the Duke responds to Brabantio in rhyming couplets: DUKE BRABANTIO The robbed that smiles steals something from the thief; He robs himself that spends a bootless grief. So let the Turk of Cyprus us beguile; We lose it not, so long as we can smile. (Act 1 Scene 3) The Duke seems to trivialise Brabantio’s complaint, and Brabantio’s overly polite reply to the Duke perhaps reflects this lighter tone. Iago’s use of rhyming couplets in Act 2 Scene 1, in which he publicly invents a number of witty proverbs for Desdemona, also contributes to a trivial, more light-hearted tone, and serves as a useful contrast to his privately aired thoughts of jealousy and malice. iiSongs At key moments in Othello, Shakespeare’s characters share their thoughts by means of song (italicised in this edition), using different rhyming schemes from the previously mentioned rhyming couplets. Iago’s drinking songs (Act 2 Scene 3) seem particularly appropriate in establishing a sense of W i l l i a m S h a k e s p e a r e ’s O t h e l l o 13