Answers to Chapter 4 Questions

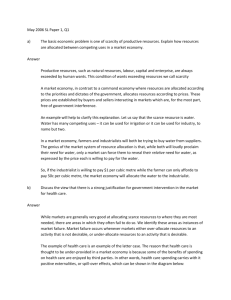

advertisement

Chapter 4 – Public Goods Chapter 4 – Public Goods 1. 3. a. Wilderness area is an impure public good – at some point, consumption becomes nonrival; it is, however, nonexcludable. b. Water from a municipal water supply is both rival in consumption and excludable. My consumption of water precludes you from consuming the same water, thus it is rival. The municipality can control who consumes water by shutting off the flow to customers, thus it is excludable. This is a useful question for showing that not all publicly owned facilities are public goods. c. Medical school education is a private good. d. Television signals are nonrival in consumption. e. An Internet site is nonrival in consumption (although it is excludable). A pure public good is nonrival in consumption, thus it is necessary to determine whether or not this is the case with the highway. That is, if the additional cost of another person “consuming” the highway is zero, then it is a public good. So, as long as the highway is not congested, then it can be considered to be a public good. However, adding another motorist to an already congested roadway can cause traffic jams that cost motorists more time to travel the highway, which would represent nonzero costs to having an additional person use the highway. Therefore, the congestion of the roadway determines whether or not we could designate it as a public good. Note that we are assuming throughout that the highway is nonexcludable. To determine whether or not the privatization of the highway is a sensible idea, it is necessary to consider the advantages and disadvantages of such an action. First, if the market structure is such that privatizing the highway would result in a monopolist in control of the highway, then this would be inefficient. Also, it would be difficult for the government to write a complete contract for maintaining the highway, which would also cause inefficiencies that would result from the privatization of the road. However, if the government owns the highway, it might not have the appropriate incentives to maintain it properly. In such a case, even ownership by a private monopolist might be a sensible solution. 6. As noted on page 65 of the textbook, the experimental results of Palfrey and Prisbrey (1997) suggest that there is some free riding, but some people do contribute. Those authors found that, on average, people contribute a portion of their resources to the provision of a public good, and there is some free riding. That was the case in Manchester, Vermont. Also, Palfrey and Prisbrey found that when the experimental game was repeated, people were more likely to free ride. This also happened in Manchester -- in the second year, participation was less. 11 Part 2 – Analysis of Public Expenditure 9. In this case, the apartment’s temperature is a public good because for the “society” of Rodolfo and Mimi, the temperature is nonrival and nonexcludable. Both get to “consume” a warmer house, and neither can exclude the other from this. The marginal benefit for society is the sum of Rodolfo’s and Mimi’s marginal benefit – e.g., $20 at 66 degrees, $17 at 67 degrees, $13 at 68 degrees, $8 at 69 degrees, and $4 at 70 degrees. The marginal benefit for society equals the marginal cost at 67 degrees; for temperatures higher than that, the marginal cost is greater than the marginal benefit for society. 10. Thelma’s marginal benefit is MBTHELMA=12-Z, and Louise’s is MBLOUISE=8-2Z. The marginal benefit for society as a whole is the sum of the two marginal benefits, or MB=20-3Z (for Z≤4), and is equal to Thelma’s marginal benefit schedule afterwards (for Z>4). The marginal cost is constant at MC=16. Setting MB=MC along the first segment gives 20-3Z=16, or Z=4/3, which is the efficient level of snowplowing. Note that if either Thelma or Louise had to pay for the entire cost herself, no snowplowing would occur since the marginal cost of $16 exceeds either of their individual marginal benefits from the first unit ($12 or $8). Thus, this is clearly a situation when the private market does not work very well. Also note, however, that if the marginal cost were somewhat lower, (e.g., MC≤8), then it is possible that Louise could credibly free ride, and Thelma would provide the efficient allocation. This occurs because if Thelma believes that Louise will free ride, Thelma provides her optimal allocation, which occurs on the second segment of society’s MB curve, which is identical to Thelma’s MB curve (note that Louise gets zero marginal benefit for Z>4). Since Louise is completely satiated with this good at Z=4, her threat to free ride is credit if Thelma provides Z>4. 12