Superstar Judges as Entrepreneurs

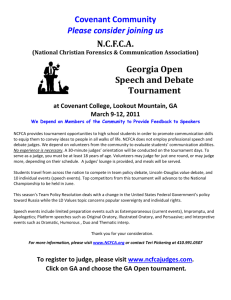

advertisement