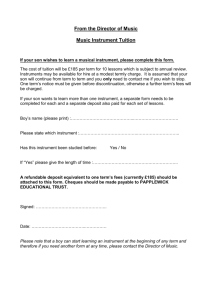

The Negotiable Instruments Act,1881

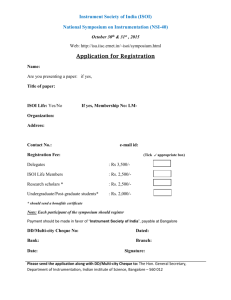

advertisement