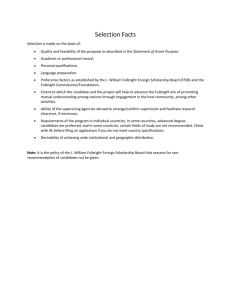

eDiscovery around the globe

advertisement