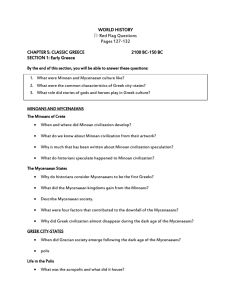

Scribes and Heroes: Divergent Poles of Early Greek Culture

advertisement