Energy-efficient Resource Utilization in Cloud Computing

advertisement

Energy-efficient Resource Utilization

in Cloud Computing

Giorgio L. Valentini1,2 , Samee U. Khan1 , and Pascal Bouvry2

1

North Dakota State University, NDSU-CIIT Green Computing

and Communications Laboratory, Department of Electrical and

Computer Engineering, Fargo, ND 58108-6050,

samee.khan@ndsu.edu

2

University of Luxembourg, Computer Science and

Communications Research Unit, Faculty of Science, Technology

and Communication, Kirchberg L-1359, Luxembourg,

{firstname.lastname}@uni.lu

Abstract

In cloud computing systems, the energy consumption of the underutilized resources accounts for a substantial amount of the actual energy

use. Inherently, a resource allocation strategy that considers the resource

utilization would increase the energy efficiency of the system. Task consolidation is an effective technique that increase the system resource utilization. Recent studies reported that energy consumption (in servers)

scales linearly with (processor) resource utilization. The aforementioned

fact highlights the significant contribution of task consolidation to reduce

in turn the energy consumption of the system. In our study, we analyze two existing energy-conscious heuristics for task consolidation. Both

heuristics aim to maximize resource utilization, with the main difference

being whether the energy consumption to execute the given task is implicitly or explicitly considered. To improve the energy efficiency of task

consolidation, we propose a bi-objective algorithm that combines the two

heuristics, in order to take advantage of both. According to our experimental results on cloud computing systems, the proposed algorithm increases the energy efficiency of the task consolidation problem, without

any performance degradation when individually compared with the two

existing energy-conscious heuristics.

1

1

Introduction

Nowadays, data communications are an important element of our daily lives.

Most of our interactions rely on gathering the information through the clientserver paradigm [7]. Over time, user demands have rapidly increased in terms of

the number of requests. To cater to the consistent amount of requests, the computational capacities and facilities must be constantly reviewed and improved.

As a drawback, the proportional nonnegligible amount of the required energy

has been often left behind to remain competitive.

The recent advocacy of “green” or “sustainable computing” (tightly coupled

with energy consumption) has been getting considerable attention. The scope of

sustainable computing goes beyond the main computing components, expanding

into a much larger range of resources associated with computing facilities as

auxiliary equipment, such as the water used for cooling and the physical/floor

space occupied by the resources.

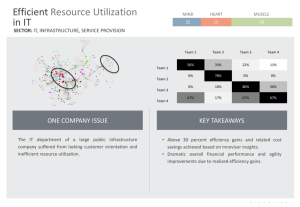

In cloud computing energy consumption and resource utilization are strongly

coupled. Specifically, resources with a low utilization rate still consume an

unacceptable amount of energy compared to the energy consumption of a fully

utilized or sufficiently loaded cloud computing. According to recent studies

([23], [28], [44], [5]), average resource utilization in most data centers can be as

low as 20%, and the average energy consumption of idle resources can be as high

as 60% (or peak power). To increase resources utilization, task consolidation

is an effective technique, greatly enabled by virtualization technologies, which

facilitate the concurrent execution of several tasks and in turn reduce the energy

consumption.

Our study uses two energy-conscious heuristics for task consolidation presented by Lee and Zomaya in [46]: MaxUtil that aims to maximize resource

utilization and ECTC (acronym for Energy-Conscious Task Consolidation —

an overview of the most common acronyms used in our study is provided in Table

1) that explicitly takes into account both active and idle energy consumption.

For a given task, ECTC computes the energy consumption based on an objective

function derived from findings reported in the literature. As stated in the findings, the energy consumption can be significantly reduced while consolidating

tasks instead of being executed stand alone. Consequently, the two heuristics reduce energy consumption without any performance degradation while assigning

a given task to a selected resource.

To take advantage of both of the methods, while always considered separately, we propose to combine the heuristics in a bi-objective model. Identifying

the resource offering the best compromise between the objectives will most likely

truly maximize the utilization rate while minimizing the energy consumption.

The main idea of the proposed model being to execute the task on the optimal

“energy-efficient” resource.

The remainder of this chapter is organized as follows. Section 2 overviews

the related work. Section 3 details the cloud computing, energy models, and

task consolidation algorithms. The bi-objective approach and the related mathematical model are described in Section 4 while the simulation results and the

2

discussions are summarized in Section 5 and Section 6, respectively. Section 7

conclude our study.

2

Related Work

Energy efficiency is an emerging research issue, recently addressed by several

researchers. For example, Khan and Ahmad in [38] were the first to use game

theoretical methodologies to simultaneously optimize system performance and

energy consumption. Since then several research works have used similar models

and approaches, which have addressed a mix of research problems related to

large scale computing systems, such as: energy proportionality, memory-aware

computations, data intensive computations, energy-efficient, grid scheduling,

and green networks ([37], [25], [10], [8], [4], [45], [19], [13], [29]).

Cloud computing and green computing paradigms are closely related and are

gaining more concerns. The energy efficiency of cloud computing became one of

the most crucial research issues. Advancements in hardware technologies [41],

such as lowpower CPUs, solid state drives, and energy-efficient computer monitors have relieved the energy issue to a certain degree. Meanwhile, a considerable

amount of software approach researches were conducted such as: scheduling and

resource allocation ([45], [22], [9], [32], [18], [20], [30]), task consolidation ([35],

[47], [21], [33]).

Virtualization technologies are a key component within task consolidation

approach. Parallel processing have been greatly eased and boosted with the

prevalence of many-core processors. That is, multiples tasks are often ran on a

single many-core processor. The parallel processing practice seems at a glance

to inherently increase performance and productivity. But the trade-off between

the aforementioned increase and the consequent energy consumption should

be carefully investigated. For example, the load imbalance (especially in the

many-core processors) is a major source of energy drainage that has motivated

multiples task consolidation studies ([35], [47], [21], [33]).

Srikantaiah et al. in [35] approached the task consolidation using the traditional bin-packing problem with two main characteristics: (a) CPU usage and

(b) disk usage. The proposed algorithm consolidates the tasks relying on the

Pareto front to balance the energy consumption and the performance. The algorithm incorporates two main steps: (1) the determination of the optimal points

from the profiling data and (2) the “energy-aware” resource allocation using the

Euclidean distance between the current selection and the optimal point within

each server.

Song et al. in [47] proposed an utility analytic model for Internet-oriented

task consolidation. The model considers task’s request for Web services such as

e-books database or e-commerce. The proposed model aims to maximize the

resource utilization and to reduce the energy consumption, offering the same

quality of services proper to the dedicated servers. The model also measure

the performance degradation of the consolidated tasks through the introduced

“impact factor” metric.

3

The task consolidation mechanisms detailed by Torres et al. in [21] and

Nathuji et al. in [33] deal with the energy reduction using unusual approaches,

especially in [21]. Unlike typical task consolidation strategies, the approach

used in [21] adopts two interesting techniques: (1) memory compression and

(2) request discrimination. The first enables the conversion of the CPU power

into extra memory capacity to allow more (memory intensive) tasks to be consolidated, whereas the second blocks useless/unfavorable requests (coming from

Web crawlers) to eliminate unnecessary resource usage. The VirtualPower approach proposed in [33] incorporates task consolidation into the power management, combining “soft scaling” and “hard scaling” methodologies. The

two methodologies (of [21] and [33]) are based on power management facilities

equipped with virtual machines and physical processors, respectively.

More recently, several noteworthy efforts on energy-aware scheduling (in

large scale distributed computing systems as grids) using game theoretic approaches have been reported ([34], [38]). Subrata et al. in [34] propose a cooperative game model and the Nash Bargaining solution to address the grid

load balancing problem. The main objective is to minimize energy consumption while maintaining a specified service quality (i.e. time and fairness). Both,

[38] and [34], deal with independent jobs through (semi-)static scheduling mode

leveraging DVFS technique to minimize the energy consumption. (For recent

literature reviews the reader is referred to [1], [11], and [12].)

3

3.1

The Energy Efficient Utilization of Resources

in Cloud Computing Systems

The Cloud Computing

The underlying system consists of a set R = {r0 , . . . , rm−1 } of m resources

(processors) that are fully interconnected in the sense that a route exists between

any two resources. It is assumed that resources are homogeneous in terms of

computing capability and capacity. The aforementioned is achieved through

the virtualization technologies [14]. Nowadays, as many-core processors and

virtualization tools are commonplace [14]. The number of concurrent tasks on

a single physical resource is loosely bounded and a cloud computing can span

across multiple geographical locations.

The cloud computing model we consider, is assumed to: (a) be confined

to a particular physical location, (b) have the inter-processor communications

performing with the same speed on all links without substantial contentions,

and (c) allow messages to be transmitted from one resource to another while a

task is being executed on the recipient resource.

3.2

Energy Model

The energy model is based on the fact that processor utilization has a linear

relationship with energy consumption. The proportional relationship means

4

Table 1: The most common acronyms used in this book chapter

Acronym

aj

BTC

d

D

dj

δ

ECTC

ej

i

Ei

ER

F

fi,j

fx

fy

m

MaxUtil

m(p)

n

normx

pi

pmax

pmin

p∆

ri

R

tj

T

ui,j

Ui

UR

τx

τ0

τ1

τ2

λ

µ

[xmin : xmax ]

[ymin : ymax ]

Description

Arrival time of a task

Bi-objective Task Consolidation (algorithm)

Distance between two points

Solution set in the two-dimension search space

Due date of a task

Normalized complement of the distance result (d)

Energy-Conscious Task Consolidation

Energy consumption of a task on a resource

Minute energy factor of a resource

Energy consumption of a resource

Energy consumption of the system

Subset (of equivalents solutions) of D

Generic cost function

Normalized result of the ECTC cost function

Result of the MaxUtil cost function

Number of resources

Maximum (rate) Utilization

Objectives vector

Number of tasks

Normalization function

Point in the two-dimensional search space

Power consumption at peak load

Power consumption in the active mode

pmax − pmin

ith resource

Set of resources

j th task

Set of tasks

Resource usage of a task

Utilization rate of a resource

Utilization rate of the system

Generic time periods of the ECTC cost function

Total processing time of a task on a resource

Time period where a task is run alone

Time period where a task is consolidated

Output / Input (ratio)

ECTC unit range

MaxUtil unit range

5

that, for a particular task, the information on the processing time and the

processor utilization is sufficient to measure the energy consumption for the

task.

At any given time, for a resource ri , the utilization Ui is defined as

Ui =

n−1

X

ui,j ,

(1)

j=0

where n is the number of tasks running at the given time and ui,j is the resource

usage of a task tj .

The energy consumption Ei of a resource ri at any given time is defined as

Ei = (pmax − pmin ) × Ui + pmin ,

(2)

where pmax is the power consumption at the peak load (or 100% utilization)

and pmin is the minimum power consumption in the active mode (or as low as

1% utilization).

Consequently, at any given time, the total utilization (UR ) as the total

energy consumption (ER ) of the system are defined as

UR =

m−1

X

Ui

and ER =

m−1

X

Ei ,

(3)

i=0

i=0

respectively, where m represents the number of resources.

The resources in the underlying system are assumed to be incorporated with

an effective power-saving mechanism for idle time slots. The mechanism results

from the significant difference in energy consumption, between active and idle

resources states. Specifically, the energy consumption of an idle resource at any

given time is set to 10% of pmin . Because the overhead to turn off and back on

a resource takes a nonnegligible amount of time, the option for idle resources

was not considered in our study or by others ([35], [47], [21], [33], [46]).

3.3

The Task Consolidation Problem

The task consolidation (also known as server/workload consolidation) problem

is the process of assigning a set T = {t0 , . . . , tn−1 } of n tasks (service requests or

simply services) to a set R = {r0 , . . . , rm−1 } of m cloud computing resources,

without violating time constraints. The main purpose remains to maximize

resource utilization and ultimately to minimize energy consumption.

Time constraints are directly related to the resource usage associated with

the tasks. More precisely, in the consolidation problem, the resources allocated

to a particular task must sufficiently provide the resource usage of that given

task. For example, a task with its resource usage requirement of 60% cannot be

assigned to a resource for which the available resource utilization at the time of

that task’s arrival is 50%.

6

3.4

3.4.1

The Task Consolidation Algorithm

Overview

Task consolidation is an effective means to manage resources, particularly in

cloud computing, both in the “short-terms” and “long-term” ([24], [31]). In

the short-term case, volume flux on incoming tasks can be “energy-efficiently”

dealt with by reducing the number of active resources and putting redundant

resources into a power-saving mode, or even turning off some idle resources

systematically. In the long-term case, cloud infrastructure providers can better

supply power and resources, alleviating the burden of excessive operational costs

due to over provisioning. Lee and Zomaya [46] focused on the short term case,

even if the results delivered by the task consolidation algorithms could be used

as an estimator in the long-term provisioning case.

Subsection 3.4.2 presents the energy conscious task consolidation heuristics

(ECTC and MaxUtil ), more commonly referred to as cost functions [46]. The

two cost functions are described side by side to highlight the main differences,

being whether the energy consumption is considered explicitly or implicitly.

More precisely, MaxUtil makes task consolidation decisions based on resource

utilization, which is a key indicator for energy efficiency.

3.4.2

The Cost Functions (ECTC and MaxUtil)

The cost function, termed ECTC, computes the actual energy consumption

of the current task by subtracting the minimum energy consumption (pmin )

required to run a task, if other tasks would be running in parallel with that

task. That is, the energy consumption of the overlapping time period among

the running tasks and the current task (tj ) is explicitly taken into account. The

cost function tends to discriminate the task being executed in a stand alone

mode.

The value fi,j of a task tj on a resource ri obtained using the ECTC cost

function is defined as

fi,j = [(p∆ × uj + pmin ) × τ0 ] − [(p∆ × uj + pmin ) × τ1 + (p∆ × uj × τ2 )], (4)

where p∆ is the difference between pmax and pmin , uj is the utilization rate of

tj , and τ0 , τ1 , and τ2 are the total processing time of tj . That is, the time period

tj is running stand alone and that tj is running in parallel with one or more

tasks, respectively. For example, consider two tasks (t0 and t1 ) that are running

in parallel on the same resource (r0 ), with t0 arriving first on the resource (see

Figure 1). While computing the result for f0,1

τ0

=

the total execution time of t1 ,

τ1

= τ0 − τ2 ,

τ2

= τ0 − τ1 ,

where τ1 is the time period where t1 will be running stand alone on r0 , and

τ2 the time period where t1 will be consolidated with t0 in r0 (the overlapping

time).

7

Figure 1: Time periods of the task t1

The rationale behind the ECTC cost function is that the energy consumption

at the lowest resource utilization is far greater than that in idle state, and the

additional energy consumption imposed by overlapping tasks contributes to a

relatively low increase.

Alternatively, the MaxUtil cost function is derived with the average utilization during the processing time of the current task, as core component. The

cost function aims to increase consolidation density and has a double benefit.

That is, (a) the implicit reduction of the energy consumption is directly related

to (b) the decreased number of active resources. In others words, MaxUtil tends

to intensify the utilization of a small number of resources.

Consequently, the value fi,j of a task tj on a resource ri using the MaxUtil

cost function is defined as

P τ0

Ui

fi,j = τ =1 ,

(5)

τ0

which is the utilization of a resource ri , as defined in Equation (1), divided by

the total execution time (τ0 ) of task tj .

3.4.3

The Task Consolidation Algorithm

In essence, for a given task, the algorithm checks every resource and identifies the

most energy-efficient resource for that task. The evaluation of the most energyefficient resource is dependent on the used heuristic (ECTC or MaxUtil ). More

specifically, on the employed cost function (referred to as fi,j ). Algorithm 1

describes the main steps of the task consolidation procedure.

3.5

Application of the Model — A Working Example

As incorporated into the energy model, energy consumption is directly proportional to the resource utilization. At a skimmed glimpse, for any two taskresource matches, the one with a higher utilization may be selected. However,

because the determination of the right match is not entirely dependent on the

8

input : tj ∈ T = {t0 , . . . , tn−1 }, R = {r0 , . . . , rm−1 }

output: r∗ ∈ R

begin

r∗ ←− ∅

forall the ri ∈ R do

Compute the cost function value fi,j of tj on ri

if fi,j > f∗,j then

r∗ ←− ri

f∗,j ←− fi,j

Assign tj to r∗

Algorithm 1: Task consolidation algorithm

current task, ECTC makes its decisions based rather on the (sole) energy consumption of that task.

Table 2 details four tasks properties specifically selected (as the working

example) to point out the divergent behavior of ECTC and MaxUtil. For each

task (tj ) we specified the arrival time (aj ), processing time (τ0 ), and utilization

or resource usage requirement (uj ). For the working example it is assumed that

pmin is set to 20 and pmax to 30. These values can be seen as rough estimates in

actual resources and can be referenced as 200 watt and 300 watt, respectively.

Conforming to the respective properties presented in Table 2, each task (tj ) will

be assigned to the more “energy-efficient” resource (ri ) selected through the

cost functions.

Figure 2 depicts the allocation of the first three tasks, where task t3 illustrates the divergence from the results obtained from the respective cost functions. Based on the (sole) energy consumption of the task, ECTC assigns t3

to the resource r1 (see Figure 2(a)), while based on the available utilization

rate of the resources, MaxUtil assigns t3 to the resource r0 (see Figure 2(b)).

The difference between the two functions becomes more prominent when task

t4 must be assigned to a resource. As illustrated in Figure 3, ECTC can only

assign t4 to the empty resource r2 (see Figure 3(a)), while MaxUtil assigns t4

to r1 (see Figure 3(b)). On our specific working example MaxUtil seems to be

more “energy-efficient” than ECTC.

Ref.[46] claimed that the performances of the algorithms can be slightly

ameliorated incorporating task migration. At each computational time, the

Table 2: Task properties

Task (tj )

0

1

2

3

4

Arrival Time (aj )

00 (sec.)

03 (sec.)

07 (sec.)

14 (sec.)

20 (sec.)

Processing Time (τ0 )

20 (sec.)

08 (sec.)

23 (sec.)

10 (sec.)

15 (sec.)

9

Utilization (uj )

40%

50%

20%

40%

70%

(a) ECTC

(b) MaxUtil

Figure 2: Depiction of the first three tasks

(a) ECTC

(b) MaxUtil

Figure 3: Final depiction for all the tasks

scheduler checks if some of the running tasks would be more “energy-efficient”,

when allocated to a different resource. If suitable, then the scheduler proceeds

with the migration. Interestingly, the benefit of using migration is not apparent.

Migrated tasks tend to be with short remaining processing times and these tasks

are most likely to hinder the consolidation of new arriving tasks. Consequently,

the incorporation of task migration increased the energy consumption.

4

4.1

Bi-Objective Approach

The Main Idea

The algorithm described in Section 3.4 uses only one of the two cost functions

at a time. In advance, it must be decided whether to use ECTC or MaxUtil.

10

According to the working example described in Section 3.5, for a given task,

the result of the two cost functions can converge as diverge. The divergence

comes from the two different considered aspects (energy consumption or resource

utilization).

The idea behind the bi-objective model is to combine the two cost functions

to only benefit from their advantages. The algorithm will then provide, as a

result, the more “energy-efficient” resource based on both of the considered

aspects. That is, the (sole) energy consumption as the resource utilization.

4.2

The Motivation

We must note that ECTC computes the energy consumption of a given task on a

selected resource, while MaxUtil looks after the more energy-efficient resource in

terms of resource utilization. The ECTC cost function is designed to encourage

resource sharing. As stated in Subsection 3.4.2, for a given resource, the energy

consumption of two tasks running in parallel is slightly superior than the energy

consumption of a task ran alone ([17], [15], [16]).

To be accurate on the computation of the energy consumption, ECTC uses

τ1 and τ2 ( see Subsection 3.4.2). Based on the time periods (τx ), the cost function gives priority to resources where concurrent tasks can be fully consolidated

and tends to discard the resources offering only a partial consolidation. The

aforementioned scenario is illustrated in Figure 2. Task t0 do not fully overlap

task t3 on resource r0 , then ECTC assigns t3 on r1 because t3 can be fully

consolidated with the task t2 .

The working example presented in Section 3.5 pointed out the main drawback of ECTC. Intuitively, the resulting divergence from the behavior of MaxUtil

can be seen as a “domino effect” that will temporarily affect the system. Being

energy efficiency (see Figure 3) the main concern of the presented heuristics, the

eventuality of a “domino effect” should not be neglected while considering the

ECTC cost function for the task consolidation problem as defined in Section

3.3. Alternatively, MaxUtil always minimizes the total number of used resources

without individually considering the energy consumption of the given task.

Because the objective of our study is to minimize the energy consumption as

the total number of used resources, our proposal combines the two cost functions

to select the resource that will most likely maximize the utilization rate and

minimize the energy consumption.

4.3

The Approach

The approach uses the two cost functions described in Equation (4) and Equation (5). The respective results are combined to build a “point” in a twodimensional search space where ECTC gives the x coordinate and MaxUtil the

y coordinate.

Originally, Equation (4) returns a value greater than zero only when applied

on a resource allowing task consolidation. Among the collected results, the

highest value identify the most “energy-efficient” resource (if τ1 6= τ0 ), while

11

the null value identifies empty (non “energy-efficient”) resources (if τ1 = τ0 ).

Figure 4 illustrates the rationale behind the ECTC cost function.

To properly construct the point in the search space, the two cost functions

have to be slightly modified. Defining the energy consumption ej of a task (tj )

on a given resource (ri ) as

ej = (p∆ × uj + pmin ),

(6)

the value fi,j of tj on ri obtained using the ECTC cost function is now defined

as

(ej × τ0 )

; if τ1 = τ0

fi,j =

(7)

((ej × τ1 ) + (p∆ × uj × τ2 )) ; otherwise.

The value of fi,j obtained using the MaxUtil cost function as

fi,j =

dj

X

Ui ,

(8)

aj

where aj is the arrival (or ready) time and dj the due date (given by aj + τ0 )

of the current task tj .

4.4

The Metric Normalization

To find the optimum point in a two-dimensional search space, the results of the

two cost functions must be normalized to a homogeneous unit scale. Because

the range of MaxUtil is defined in a continuous unit scale from 1 to 100, the

result of ECTC will be normalized to the unit scale of MaxUtil, from now on

formally referred as [ymin : ymax ].

For a given task (tj ) the utilization on a selected resource (ri ) is directly dependent on the speed (operations per seconds) of the CPU on that resource. The

amount of time needed for the resource to accomplish the task is derived from

the speed of that CPU. Based on the above information (speed and time) of a

Figure 4: Structure of the ECTC cost function

12

selected resource, the maximum value (xmax ) returned by the ECTC cost function can be then estimated and the ECTC unit range defined by the bounded

interval going from 0 to xmax .

Defining xmin as the lower bound and xmax as the upper bound of the

ECTC unit range, the normalization of the (ECTC ) metric on the unit scale

[ymin : ymax ] is given as

normx

:

normx

=

[xmin : xmax ] −→ [ymin : ymax ],

(fi,j − xmin ) × (ymax − ymin )

.

xmax − xmin

(9)

As mentioned in the Section 4.3, for a set of resources (R = {r0 , . . . , rm−1 })

the highest value (fi,j ) returned by the cost functions identify the most “energyefficient” resource (see Algorithm 1). Because we modified the original ECTC

cost function (see Equation (7)), the complement of normx , denoted as fx , must

be considered

fx

:

[ymin : ymax ] −→ [ymin : ymax ],

fx

=

ymax − normx ,

(10)

to coherently build the normalized two-dimensional point in the evaluation

space.

4.5

The Evaluation Space

Renaming the respective returned value from the cost functions as fx for (the

normalized) ECTC and fy for MaxUtil, the coordinates of the point pi for a

selected resource ri is defined as

pi = (fx ; fy ),

and among all the points, the optimum will be the higher point giving the best

compromise between the results of the two cost functions (fx and fy ). The ideal

optimum points must then belong to the domain space of the function

f (x) = y.

(11)

Therefore, the closer the pi is to the line (given by Equation (11)), the more

probable it is for that point to be the local optimum. For every pi , the respective

distance to the corresponding ideal optimum point will be computed and referred

to as

d = |fx − fy |.

(12)

The smaller the value of d, the closer the pi is to the respective ideal optimum

point belonging to the domain space (of Equation (11)). This also will be the

best compromise offered by the given point. The value of d will finally be

the main estimator of the selection of the best candidate among the equivalent

optimum solutions.

13

4.6

4.6.1

Selection of The Best Candidate

The Mathematical Model

There exist many methodologies to find the optimum solution among the solution set ([36], [2], [6]). The main idea would be to avoid having to compare all

points within the solution space at every decision point.

The first step of our approach consists of constructing the solution search

space based on the results of the two cost functions. The optimum solution will

be identified and updated at the same time the solution set is constructed. By

the time the solution set is built the optimum solution will be identified. The

search operation will rely on the Pareto dominance criteria ([40], [42], [43]). The

first point of the solution space will be set as the “current” optimum solution.

The “current” solution will then be compared to the next (new) created point

and updated, if needed.

Formally, let D be a finite set. For a fixed natural k, a mapping

m

:

D −→ Rk ,

m(p)

=

(m1 (p), . . . , mk (p)),

can be defined, whose components mi : D −→ R, ∀i : 1 ≤ i ≤ k, are denoted as

objectives and Rk is the evaluation (or measurement) space of the elements of

D. As already mentioned, our approach maximizes the considered objectives.

Accordingly, given p and q, the two elements of D, p dominates q, and it is

represented as p q, if and only if,

∀i : 1 ≤ i ≤ k : (mi (p) ≥ mi (q)) ∧ ∃j : 1 ≤ j ≤ k : mj (p) 6= mj (q) . (13)

From our analysis and discussion of Section 4.5 it follows that

m(p) = (fx , fy ),

where m(p) belongs to the homogeneous unit scale [ymin : ymax ].

4.6.2

The Algorithm

For each resource, the algorithm constructs the corresponding point in the evaluation space (D) and verify if the new created solution dominates the current

optimum solution. If the aforementioned case is verified, then the algorithm updates the optimum solution. Algorithm 2 details the main steps of the procedure

used to identify the optimal solution from the solution set D.

4.7

Processing of Equivalent Solutions

The design of Algorithm 2 does not identify equivalent solutions. A double

dominance check must be introduced and the equivalent solutions added to a

subset F (F ⊆ D). Because the optimum solution may change by the time

the domain space (D) is constructed, F must “reset” each time a new optimum

14

input : tj ∈ T = {t0 , . . . , tn−1 }, R = {r0 , . . . , rm−1 }

output: r∗ ∈ R

begin

r∗ , optimum ←− ∅

forall the r ∈ R do

x ←− fx

y ←− fy

result ←− (x, y)

if result optimum then

optimum ←− result

r∗ ←− r

Algorithm 2: Bi-Objective procedure

point is identified. This will ensure that the subset only contains the equivalent

solutions to the latest optimum point.

By the time the solution space is constructed, the equivalent optimum points

will be identified. The selection among the equivalent solutions belonging to F,

if any, will rely on d. Because our approach maximizes the considered objectives,

the complement of d, denoted as δ, will be considered according the formula

[ymin : ymax ] −→ [ymin : ymax ],

δ

:

δ

= ymax − d.

(14)

The aforementioned selection process will sequentially compare each f ∈ F

with the actual optimum point. The actual optimum will then be updated

based on the δ parameter, or on the sum of the two coordinates ((fx , fy ) ∈ pi ),

if the pair share the same value for the x (energy consumption) or y (utilization)

coordinate.

4.8

The Bi-objective Task Consolidation Algorithm

The algorithm constructs, for each resource, the corresponding point in the

evaluation space (D) and verifies if the: (a) new created solution dominates the

current optimum solution or (b) two solutions are equivalent, otherwise. If the

fist aforementioned case is verified, then the algorithm updates the optimum

solution and “reset” the equivalent solutions subset (F). Otherwise the algorithm update F with the new created solution if suitable. Among the equivalent

solutions of F, the algorithm identifies the optimum solution through: (c) the

δ parameter or (d) the sum of the two objectives. Algorithm 3 describes the

entire procedure that identifies the optimal solution from the solution set D and

the related subset F.

15

input : tj ∈ T = {t0 , . . . , tn−1 }, R = {r0 , . . . , rm−1 }

output: r∗ ∈ R

begin

r∗ , optimum, F ←− ∅

forall the r ∈ R do

x ←− fx

y ←− fy

δ ←− (ymax − |x − y|)

result ←− (x, y)

if (result optimum) then

optimum ←− result

r∗ ←− r, F ←− ∅

F ←− F ∪ (result, r, δ)

if ((result 6 optimum) ∧ (optimum 6 result)) then

F ←− F ∪ (result, r, δ)

forall the (f, r, δ) ∈ F do

if ((fx 6= optimumx ) ∧ (fy 6= optimumy )) then

if (δ > δoptimum ) then

optimum ←− f

δoptimum ←− δ

r∗ ←− r

else

if ((fx + fy ) > (optimumx + optimumy )) then

optimum ←− f

δoptimum ←− δ

r∗ ←− r

Algorithm 3: BTC Algorithm

16

4.9

An Intuitive Example

Conforming to the data provided in Table 2, the problem will be now solved using the BTC algorithm, where for the normalization procedure into the MaxUtil

unit scale, ymin have been set to 1 and ymax to 100. Table 3 summarizes the

numerical results of Equation (7), Equation (8), Equation (10), and Equation

(14) presented in Section 4. For each task (tj ) a maximum number of three

resources (ri ) are identified. ECTC and MaxUtil represent the values of the

respective cost functions (see Equation (7) and Equation (8)) for a given task

(tj ) on the selected resource (ri ). The coordinates of the constructed point in

the two-dimensional search space are denoted by pi (see Equation (10)), and δi

(see Equation (14)), which shows the normalized complement of the distance (d)

from the point (pi ) and the corresponding ideal optimum point for the selected

resource (ri ). If at the arrival time of a task (tj ) the selected ri had not enough

available resource utilization rate for the given tj , then that resource will not be

shown in the table. The double right arrow (⇒) identifies the optimum result

selected by the algorithm.

For example, task t0 requires: (a) 40% of available resource utilization, (b)

20 seconds to be executed by a selected resource, and (c) arrives at time t equal

to zero. In line with the aforementioned task’s properties, when evaluating the

resource r0 , (d) ECTC returns a (normalized) value equal to 48 and (e) MaxUtil

a value equal to 40 (because ran in stand alone mode). The coordinates of the

corresponding point p0 are given based on the result obtained in: (d) and (e).

The x coordinate is computed substracting 48 (result obtained in (d)) from 100

(value set as ymax ), equal to 52 (fx ). The y coordinate is equal to 40 (fy ),

as computed in (e). From the coordinates (fx and fy ) of p0 we compute (f)

the distance (d = |fx − fy |), equal to 12. The value of δ is then computed

substracting the result obtained in (f) to ymax (δ = 100 − 12) and is equal to

88.

Table 3: Results of the BTC’s computations

Task (tj )

t0

t1

t2

t3

t4

Resource (ri )

⇒ r0

r1

r2

⇒ r0

r1

r2

⇒ r1

r2

⇒ r0

r1

r2

⇒ r1

r2

ETCT

48

48

48

18

20

20

51

51

12

20

24

20

41

17

MaxUtil

40

40

40

90

50

50

20

20

80

60

40

90

70

pi (fx ; fy )

(52; 40)

(52; 40)

(52; 40)

(82; 90)

(80; 50)

(80; 50)

(49; 20)

(49; 20)

(88; 80)

(80; 60)

(76; 40)

(80; 90)

(59; 70)

δi

88

88

88

92

70

70

71

71

92

80

64

90

89

The resulting two-dimensional search space for the evaluation of task t0 on

the three considered resources is illustrated in Figure 5(a). For a given task

(tj ), if at least two resources (ri ) share the same coordinates (e.g. task t0 in

Table 3), then that point is only represented once. In the aforementioned table

and figure, the point p0 identifies r0 as the optimum (most “energy-efficient”)

resource evaluated through the BTC algorithm. Consequently, the algorithm

assigns t0 to r0 as depicted in Figure 6.

Figure 5 illustrates the two-dimensional search spaces for each task, in agreement with the informations contained in Table 3. Among the points within the

evaluation space, the (black) full dot (within the subset F) identifies the optimum point (resource) for the given task, while the line given by Equation (11)

represents the ideal optimum points.

Throughout the numerical results summarized in the aforementioned table

(visually reflected in Figure 5), the BTC algorithm evaluates and identifies

the optimum solution simultaneously considering two aspects: (a) the resource

utilization rate and (b) the energy consumption implied by a given task. As a

result, the solution selected by the algorithm is the “energy-efficient” optimum

in terms of both (a) and (b).

Figure 6 depicts an additional representation of the optimum scenario provided by the algorithm after completing the evaluation of our intuitive example.

The four tasks have been assigned only on two resources. As expected the algorithm maximized the resource utilization rate simultaneously minimizing the

system’s energy consumption. For each given task of our particular example,

BTC selected the same solutions than MaxUtil (see Figure 3(b)). The main difference being that BTC always guarantee Pareto optimality in terms of energy

efficiency.

5

5.1

Simulation Results

Simulation Setup

The simulations were carried out using the MPICH2 framework [27]. A highperformance and widely portable implementation of the Message Passing Interface (MPI) standard [26]. MPICH2 has two main goals. First, to provide an

MPI implementation that efficiently supports different computation and communication platforms (including commodity clusters, high-speed networks, and

proprietary high-end computing systems). Second, to enable cutting-edge research in MPI through an easy-to-extend modular framework for other derived

implementations.

Throughout the simulations, the resource usage of the generated tasks was

random and uniformly distributed between 4% and 95% (or 0.04 and 0.95). The

minimum utilization rate of 4% avoids generating processing times lower than

1 millisecond (τ0 < 1 ms).

The architecture used to simulate the environment followed the Master-Slave

scheme. One selected resource (the Master) was in charge of : (a) dynamically

18

(a) t0

(b) t1

(c) t2

(d) t3

(e) t4

Figure 5: The two-dimensional search space of the BTC algorithm

19

Figure 6: The Final result identified by the BTC algorithm

generating the next task and (b) selecting the “optimum” resource (the Slave)

to execute that task, according to the selected energy efficiency policy.

Because cloud computing systems are always ready to perform the next

incoming request, our problem becomes time and space dependent. That is,

every future decision will be directly dependent on the previous decision.

To properly emulate the system, the simulation was divided into three steps:

(a) the “seeding”, (b) the “training” (or warm-up) period, and (c) the (window)

“run”. First, the resources are filled with “concurrent” tasks (seeding operation) generated on a nonlinear “time dependent” distribution, aiming to simulate some ongoing previous requests. Secondly, the new tasks were randomly

generated and assigned to the “optimum” resource (training period) based on

the current work-flow of the system. Finally, the run evaluates the heuristics

based on a predefined interval of tasks. More precisely, the seeding operation

creates the environment, the training period stabilizes the simulation, and the

run evaluates the algorithm over a window consisting of one hundred thousand

(105 ) tasks dynamically generated and assigned among the system. Figure 7

illustrates the aforementioned steps.

The length of the warm up (“training”) period needs to be evaluated, if the

state of the model at starting time does not represent the steady state of the

actual system. The point at which the model seems real for the first time could

be estimated as the warm-up time. In our experiment, the warm-up period

is the amount of (simulated) tasks that need to run before the data collection

begins [3]. The switch from the “training” to “run” occurs dynamically based on

the result given by the “output to input” ratio (λ/µ), also know as the system

utilization. At each task assignment, λ and µ represent the number of outgoing

and incoming tasks, respectively. The ratio (λ/µ) aids in the monitoring of the

system, allowing a dynamic start to the evaluation of the selected heuristic in an

environment secured from collapse. The “run” starts as soon as the simulation

reaches the steady state. In our environment, we considered the steady sate

20

Figure 7: The three steps of the simulation

from any value of the ratio (λ/µ) greater than 0.50.

The performance and behavior of the BTC algorithm were evaluated compared to the individual results obtained with Algorithm 1 presented in Section

3. Initially setting MaxUtil and successively ECTC as the cost function.

Given that the main objective of our experiment was to maximize the utilization while minimizing the energy consumption, at each task assignment two

global factors were logged: (a) the total rate of resources utilization (UR ) and

(b) the cumulated amount of the energy consumption (ER ) of the system (see

Equation (3)). Both (a) and (b) aim to observe the global behavior in terms of

energy efficiency of the selected algorithms.

To compare the scalability of the different heuristics, at each task assignment,

we observed the speed intended as the time (in microseconds (µs)) to select the

“optimum” resource. The recorded computation relied on the MPICH2 time

function (MPI Wtime).

The simulation environment was developed based on four different topologies: (a) 10 and 20 resources of 4 cores and (b) 5 and 10 resources of 8 cores.

The number of cores available on a resource bound the maximum number of

tasks that can be concurrently executed on a selected resource. The experiment follows the specifications of the task consolidation problem as explained

in Section 3.3.

For each resource a central processing unit (CPU) of 2, 048 GHz was assumed

and equally shared between the predefined numbers of cores. The process to

randomly generate the tasks is as follow. Initially, a bounded number is generated corresponding to the number of operations (per second) needed to perform

that given task. Being bounded, the aforementioned prevents the resulting generated task to overflow the computational capabilities of the available resources

(i.e. uj > 100% for a given task tj ). The bounded interval that generates the

number of operations (per second) is directly dependent on: (a) the predefined

21

CPU speed and (b) the number of cores. From (a) and (b) we compute the sole

core speed. Successively, dividing the number of operations (per second) by the

sole core speed we obtain the processing time (in milliseconds (ms)) needed for

the given task to be executed on a selected resource. Finally, the utilization

rate of that task is derived by dividing the processing time by the predefined

CPU speed. Table 4 summarizes the parameters used to set our experiment.

Table 4: Parameters of the simulation environment

Type

General

4 cores

8 cores

5.2

5.2.1

Parameter

CPU speed

Window of tasks

Resource usage

[xmin : xmax ]

[ymin : ymax ]

pmin

pmax

λ

µ

Value

2,048 GHz

100 000

[0.04 : 0.95]

[1 : 20 000]

[1 : 99]

20

30

0.50

Single core speed

Number of resources

Number of operations per second

Single core speed

Number of resources

Number of operations per second

512 MHz

10, 20

[1 : 9 400]

256 MHz

5, 10

[1 : 4 700]

Results

Energy Efficiency

The results presented in the following graphs aim to evaluate the energy efficiency of the three heuristics: (a) MaxUtil, (b) ECTC, and (c) the Bio-objective

Task Consolidation (BTC ) algorithm.

For each of the heuristic we depicted four graphs (see Figure 8, Figure 9,

and Figure 10) that showed the behavior, in terms of energy efficiency and task

consolidation, among the four selected topologies: (a) 10 and 20 resources of 4

cores and (b) 5 and 10 resources of 8 cores. Within the aforementioned figures,

the solid (blue) line represents the total utilization rate of the system while the

dashed (red) line the energy consumption. The sampling rate for the collection

of the system’s status was performed at each task assignment. The y axis shows

the utilization as the (normalized) energy consumption unit scale, while the task

index was reported following a logarithmic scale in the x axis.

Figure 8 and Figure 9 corresponds to MaxUtil and ECTC, respectively, while

Figure 10 to the BTC algorithm. From our results, no significant differences

can be pointed out among the three heuristics conforming to the task consolidation problem. Consequently, MaxUtil, ECTC, and the BTC algorithm can

be considered “energy efficiently” equal.

22

23

(d) 8 cores - 10 resources

(b) 4 cores - 20 resources

Figure 8: Results using the MaxUtil cost function

(c) 8 cores - 5 resources

(a) 4 cores - 10 resources

24

(d) 8 cores - 10 resources

(b) 4 cores - 20 resources

Figure 9: Results using the ECTC cost function

(c) 8 cores - 5 resources

(a) 4 cores - 10 resources

25

(c) 8 cores - 5 resources

(d) 8 cores - 10 resources

(b) 4 cores - 20 resources

Figure 10: Results using the BTC algorithm

(a) 4 cores - 10 resources

5.2.2

Speed Analysis

Figure 11 depicts the behavior of the heuristics in term of speed. The time

needed to select the “optimum energy-efficient” resource among the system at

each task assignment. The solid (blue) line represents the BTC algorithm, while

the dashed (red) and the dotted (cyan) lines represent MaxUtil and ECTC, respectively. The data are represented following a logarithmic scale on both of the

axis, where the task number is provided on the x and the time (in microseconds

(µs)) on the y axis.

Among the considered aspects (utilization rate and energy consumption),

MaxUtil only considers the available utilization rate, because developed to

maximize task consolidation. ECTC considers the available utilization rate

(as MaxUtil ) combined with the time periods (τx ) to predict the energy consumption of the given task on a selected resource, designed to consolidate task

energy-efficiently. When compared, MaxUtil proved to be faster than ECTC.

The BTC algorithm uses the solutions generated by MaxUtil and ECTC to

construct the (bi-objective) evaluation space, conferring to the algorithm the

more complex election of the optimum solution. Consequently, our proposed

algorithm was the slowest when compared, but resulted being the heuristic that

provided the best “energy-efficient” solutions.

6

Discussion of Results

Recalling Section 3, our study described two existing heuristics: (a) MaxUtil

and (b) ECTC. The main difference between (a) and (b) being whether the

energy consumption is implicitly or explicitly considered. MaxUtil proved to

maximize task consolidation reducing in turns the number of used resources.

Consequently, the decreased number of used resources directly reduces the energy consumption of the system. According to the aforementioned MaxUtil was

defined as implicitly energy-efficient. Alternatively, ECTC was developed to

consolidate tasks that can be fully overlapped, tending to discard the consolidation option for partial-overlapping tasks. The main concern of ECTC remain

the energy consumption of the given task on the selected resource, that must

be minimal. Consequently, the aforementioned property defined ECTC as explicitly energy-efficient.

The rationale behind the ECTC cost function relies on the energy consumption during the time periods (τx ) and pmin , the minimum power consumption

in the active mode. Designed to consolidate only full overlapping tasks, ECTC

allows the minimum power consumption pmin to be ignored for that given task,

independently from the number of consolidated tasks. The estimation of the energy consumption of the given task will be fully dependent on the time period

given by τ2 , the time period τ1 being respectively null (see Figure 4).

When the consolidated task can only be partially overlapped, for that task,

ECTC considers the energy consumption as follows. The time period τ1 with

the implied power consumption in the active mode (pmin ) is added to the energy

26

27

(d) 8 cores - 10 resources

(b) 4 cores - 20 resources

Figure 11: Computational speed of the heuristics

(c) 8 cores - 5 resources

(a) 4 cores - 10 resources

consumption during the time period τ2 (see Figure 1). For example, if n tasks

are consolidated based on partial overlap, pmin must be considered n times on

n different (time periods) τ1 . Formally, let the time period (τ1 ) corresponding

to the task (tj ) on a selected resource (ri ) defined as τ1j , the total power consumption of that resource must then be increased by the minute energy factor

n

X

i = pmin ×

τ1j ,

(15)

j=0

which is what ECTC tries to avoid.

Because the time periods constraints are strongly related to the minimum

power consumption in the active mode, ECTC can “diverge” by taking decisions

that generate the “domino effect” as mentioned in Section 4.2. From the energy

efficiency point of view, MaxUtil saves energy minimizing (when possible) the

number of used resources of the system, while ECTC prioritizes the consolidation of full overlapping tasks. More precisely, ECTC runs as much as possible

concurrent tasks under the same pmin to save that energy consumption.

The proposed bi-objective algorithm named BTC was built from the two

heuristics (MaxUtil and ECTC ). The BTC algorithm identifies the resource

offering the best compromise between the results of the two cost functions, consolidating tasks energy-efficiently. The closer the normalized results (see Section

4), the more the offered solutions will be energy-efficiently converging. Consequently, divergent solutions will be dismissed by the BTC algorithm discarding

the possibility of generating the domino effect as mentioned above.

7

Conclusion

Task consolidation, especially in cloud computing systems, became an important

approach to streamline resource usage that in turn improves energy efficiency.

Two existing energy-conscious heuristics for task consolidation, offering different energy-saving possibilities, were analyzed in our study. For both heuristics

we identified the corresponding drawback and proposed, as a (single) solution,

the Bi-objective Task Consolidation (BTC ) algorithm. The aforementioned algorithm combines the two heuristics to construct the corresponding bi-objective

search space. Within the domain space, the optimum solution set and the corresponding optimum solution are selected through the Pareto dominance criteria

and the Euclidean distance, respectively. The efficiency of the proposed algorithm was proved thought the evaluation study, consisting of different simulations carried out using the MPICH2 framework. Concerned about the energy

efficiency of the system and the scalability of the proposed algorithm, at each

task assignment we observed three main aspects: the total energy consumption,

the total resource utilization, and the time needed to select the optimum solution. To evaluate the performance of the BTC algorithm according to the

aforementioned criteria, the two heuristics were individually implemented and

used as key indicator for the energy efficiency and the scalability. Despite the

28

more elaborate selection of the optimum solution, our study reported that the

proposed BTC algorithm was the slowest when compared, but resulted being

the heuristic that provided the best “energy-efficient” solution. The result of

our study should not only contribute on the reduction of electricity bills of

cloud computing infrastructure providers, but also promote the combinations

of existing techniques toward optimized models for energy efficient use, without

performance degradation.

29

References

[1] A. Beloglazov, R. Buyya, Y. C. Lee, and A. Y. Zomaya, “A Taxonomy

and Survey of Energy-Efficient Data Centers and Cloud Computing Systems,”, Advances in Computers, 82, 2011, pp. 47-111.

[2] A. Ghosh and S. Dehuri, “Evolutionary Algorithms for Multi-Criterion

Optimization: A Survey”, International Journal of Computing & Information Sciences, 2(1), April 2004.

[3] A. Mehta, “Smart Modeling - Basic Methodology and Advanced Tools”,

In Proc 32nd Conference on Winter Simulation (WSC ’00), Orlando, FL,

USA, 1, 2000, pp. 241-245.

[4] A. Y. Zomaya, “Energy-Aware Scheduling and Resource Allocation for

Large-Scale Distributed Systems”, in 11th IEEE International Conference on High Performance Computing and Communications (HPCC),

Seoul, Korea, 2009.

[5] C. Lefurgy, X. Wang, and M. Ware, “Server-level power control”, in Proc

4th IEEE International Conference on Autonomic Computing (ICAC

’07), Jacksonville, FL, USA, June 2007, pp. 4.

[6] C. A. Coello Coello, “A Comprehensive Survey of Evolutionary Based

Multiobjective Optimization Techniques”, Knowledge and Information

Systems, 1(3), Citeseer, 1999, pp. 129-156.

[7] D. Grigoras, “Advanced Environments, Tools, and Applications for Cluster Computing”, NATO Advanced Research Workshop, IWCC 2001,

Mangalia, Romania, September 2001, Lecture Notes in Computer Science, 2326, Springer, 2002.

[8] D. Kliazovich, P. Bouvry, and S. U. Khan, “DENS: Data Center

Energy-Efficient Network-Aware Scheduling”, in ACM/IEEE International Conference on Green Computing and Communications (GreenCom), Hangzhou, China, December 2010, pp. 69-75.

[9] D. Zhu, R. Melhem, and B. R. Childers, “Scheduling with dynamic voltage/speed adjustment using slack reclamation in multiprocessor realtime systems”, IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems,

14(7), pp. 686-700.

[10] F. Pinel, J. Pecero, P. Bouvry, and S. U. Khan, “Memory-aware Green

Scheduling on Multi-core Processors”, in 39th IEEE International Conference on Parallel Processing (ICPP), San Diego, CA, USA, September

2010, pp. 485-488.

30

[11] F. Pinel, J. E. Pecero, S. U. Khan, and P. Bouvry, “A Review on Task

Performance Prediction in Multi-core Based Systems”, in 11th IEEE

International Conference on Scalable Computing and Communications

(ScalCom), Pafos, Cyprus, September 2011.

[12] G. L. Valentini, W. Lassonde, S. U. Khan, N. Min-Allah, S. A. Madani,

J. Li, L. Zhang, L. Wang, N. Ghani, J. Kolodziej, H. Li, A. Y. Zomaya,

C.-Z. Xu, P. Balaji, A. Vishnu, F. Pinel, J. E. Pecero, D. Kliazovich,

and P. Bouvry, “An Overview of Energy Efficiency Techniques in Cluster

Computing Systems”, Cluster Computing. (Forthcoming)

[13] G. Valentini, C. J. Barenco Abbas, L. J. Garcia Villalba, L. Astorga,

“Dynamic multi-objective routing algorithm: a multi-objective routing

algorithm for the simple hybrid routing protocol on wireless sensor networks”, IET Communications, 4(14), 2010, pp. 1732-1741.

[14] I. Menken and G. Blokdijk, “Virtualization - The Complete Cornerstone

Guide to Virtualization Best Practices: Concepts, Terms, and Techniques for Successfully Planning, Implementing and Managing Enterprise IT Virtualization Technology”, Emereo Publishing, October 2008.

[15] J. Choi, S. Govindan, B. Urgaonkar, and A. Sivasubramaniam,“Profiling,

Prediction, and Capping of Power Consumption in Consolidated Environments ”, in 16th International Symposium on Modeling, Analysis,

and Simulation of Computer and Telecommunication Systems (MASCOTS 2008), Baltimore, MD, USA, September 2008, pp. 3-12.

[16] J. Choi, S Govindan, J. Jeong, B Urgaonkar, and A. Sivasubramaniam,

“Power Consumption Prediction and Power-Aware Packing in Consolidated Environments”, in IEEE Transactions on Computers, 59(12),

2010, pp. 1640-1654.

[17] J. G. Koomey, “Estimating total power consumption by servers in the

U.S. and the world”, Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory, Stanford

University, 2007.

[18] J. J. Chen and T. W. Kuo , “Multiprocessor energy-efficient scheduling

for real-time tasks with different power characteristics”, in Proc International Conference on Parallel Processing (ICPP ’05), 2005, pp. 13-20.

[19] J. Kolodziej, S. U. Khan, and F. Xhafa, “Genetic Algorithms for Energyaware Scheduling in Computational Grids”, in 6th IEEE International

Conference on P2P, Parallel, Grid, Cloud, and Internet Computing

(3PGCIC), Barcelona, Spain, October 2011.

[20] J. Moore, J. Chase, P. Ranganathan, and R. Sharma, “Making scheduling cool: temperature-aware workload placement in data centers”, in

Proc USENIX annual technical conference, 2005.

31

[21] J. Torres, D. Carrera, K. Hogan, R. Gavalda, V. Beltran, and N. Poggi,

“Reducing wasted resources to help achieve green data centers”, in Proc

4th workshop on High-Performance, Power-Aware Computing (HPPAC

’08), 2008.

[22] K. H. Kim, R. Buyya, and J. Kim, “Power aware scheduling of bag-oftasks applications with deadline constraints on DVS-enabled clusters”,

in Proc 7th IEEE international symposium on Cluster Computing and

the Grid (CCGrid ’07), 2007, pp. 541-548.

[23] L. Barroso and U. Holzle, “The case for energy-proportional computing”,

IEEE Computer, 40(12), 2007, pp. 33-37.

[24] M. G. Jaatun, G. Zhao, and C. Rong ,“Cloud Computing: First International Conference, CloudCom 2009”, China, December 2009, Lecture

Notes in Computer Science, 5931, Springer.

[25] M. Guzek, J. E. Pecero, B. Dorrosoro, P. Bouvry, and S. U. Khan,

“A Cellular Genetic Algorithm for Scheduling Applications and Energyaware Communication Optimization”, in ACM/IEEE/IFIP International Conference on High Performance Computing and Simulation

(HPCS), Caen, France, June 2010, pp. 241-248.

[26] Message Passing Interface (MPI), http://www.mpi-forum.org/, accessed

April 2011.

[27] MPICH2, http://www.mcs.anl.gov/research/projects/mpich2/, release

1.3.2p1, accessed April 2011.

[28] P. Bohrer, E. Elnozahy, T. Keller, M. Kistler, C. Lefurgy, and R. Rajamony, “The case for power management in web servers”, Power Aware

Computing, Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2002, pp. 261-289.

[29] P. Ruiz, B. Dorronsoro, G. Valentini, F. Pinel, P. Bouvry, “Optimization

of the Enhanced Distance Based Broadcasting Protocol for MANETs”,

Journal of Supercomputing, Springer, 55, 2011, pp. 1-28.

[30] Q. Tang, S. K. Gupta, and G. Varsamopoulos, “Energy-efficient thermalaware task scheduling for homogeneous high-performance computing

data centers: a cyber-physical approach”, IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed Systems, 19(11), 2008, pp. 1458-1472.

[31] R. Buyya, J. Broberg, and A. M. Goscinski, “Cloud Computing: Principles and Paradigms”, Wiley, 1st edition, March 2011.

[32] R. Ge, X. Feng and K. W. Cameron, “Performance-constrained distributed DVS scheduling for scientific applications on power-aware clusters”, in Proc the ACM/IEEE conference on SuperComputing (SC ’05),

2005, pp. 34-44.

32

[33] R. Nathuji and K. Schwan K, “VirtualPower: coordinated power management in virtualized enterprise systems”, in Proc 21st ACMSIGOPS

Symposium on Operating Systems Principles (SOSP ’07), 2007, pp. 265278.

[34] R. Subrata, A. Y. Zomaya, and B. Landfeldt, “Cooperative power-aware

scheduling in grid computing environments”, Journal of Parallel and

Distributed Computing, 70(2), pp. 84-91.

[35] S. Srikantaiah, A. Kansal, and F. Zhao, “Energy aware consolidation for

cloud computing”, in Proc USENIX HotPower’08: Workshop on Power

Aware Computing and Systems in Conjunction with OSDI, San Diego,

CA, USA, December 2008.

[36] R.T. Marler and J.S. Arora, “Survey of multi-objective optimization

methods for engineering”, Published online: 23 March 2004, Springer.

[37] S. U. Khan, “A Self-adaptive Weighted Sum Technique for the Joint Optimization of Performance and Power Consumption in Data Centers”, in

22nd International Conference on Parallel and Distributed Computing

and Communication Systems (PDCCS), Louisville, KY, USA, September 2009, pp. 13-18.

[38] S. U. Khan and I. Ahmad, “A Cooperative Game Theoretical Technique

for Joint Optimization of Energy Consumption and Response Time in

Computational Grids”, IEEE Transactions on Parallel and Distributed

Systems, 20(3), 2009, pp. 346-360.

[39] T. Kuroda, K. Suzuki, S. Mita, T. Fujita, F. Yamane, F. Sano, A. Chiba,

Y. Watanabe, K. Matsuda, T. Maeda, T. Sakurai, and T. Furuyama,

“Variable supplyvoltage scheme for lowpower highspeed CMOS digital

design”, IEEE Journal of Solid-State Circuits, 33(3), 1998, pp. 454-462.

[40] V. Pareto, “Manuale di Economia Politica”, Societa Editrice Libraria,

Milano, Italy, 1906. Translated into English by A. S. Schwier, “Manual

of Political Economy”, New York: Macmillan, 1971.

[41] V. Venkatachalam and M Franz, “Power reduction techniques for microprocessor systems”, ACM Computing Surveys, 37(3), 2005, pp. 195-237.

[42] W. Stadler, “A survey of multicriteria optimization or the vector maximum problem, part I: 1776-1960”. Journal of Optimization Theory and

Applications, 29(1), 1979, pp. 1-52.

[43] W. Stadler, “Applications of Multicriteria Optimization in Engineering

and the Sciences (A Survey)”, in M. Zeleny (ed.) Multiple Criteria Decision Making — Past Decade and Future Trends, Greenwich, CT: JAI,

1984.

33

[44] X. Fan, X.-D. Weber, and L. A. Barroso, “Power provisioning for a

warehouse-sized computer”, in Proc 34th annual International Symposium on Computer Architecture (ISCA ’07), 2007, pp 1323.

[45] Y. C. Lee, and A. Y. Zomaya, “Minimizing Energy Consumption for

Precedence-Constrained Applications Using Dynamic Voltage Scaling,”

in 9th IEEE/ACM International Symposium on Cluster Computing and

the Grid (CCGrid), Shanghai, China, 2009, pp. 92-99.

[46] Y. C. Lee and A. Y. Zomaya, “Energy efficient utilization of resources in

cloud computing systems”, published online: 19 March 2010, Springer.

[47] Y. Song, Y. Zhang, Y. Sun, and W. Shi, “Utility analysis for internetoriented server consolidation in VM-based data centers”, in Proc IEEE

international conference on cluster computing (Cluster ’09), 2009.

34