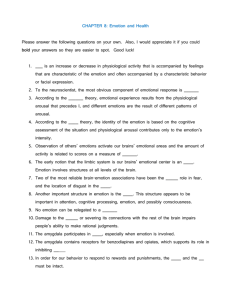

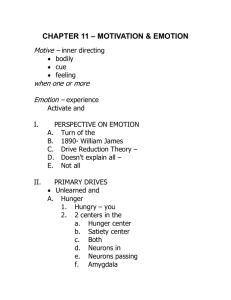

11 Motivation and Emotion

advertisement