Electronic Data Interchange, Extranets, XML, and Web Services

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-200

Tutorial

6

Electronic Data

Interchange, Extranets,

XML, and Web

Services

Content

T6.1

Electronic Data Interchange (EDI)

T6.2

Extranets

T6.3

XML

T6.4

Web Services

W-200

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-201

T6.1

Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) W-201

T6.1

Electronic Data Interchange (EDI)

We defined EDI in Chapter 10. Here we present more details.

One of the early contributions of IT to facilitate B2B e-commerce and other IOS transactions is the electronic data interchange (EDI). (see en.wikipedia.org/wiki/

Electronic_Data_Interchange)

TRADITIONAL EDI Major Components of EDI.

The following are the major components of EDI:

• EDI translators. An EDI translator converts data into a standard format before it is transmitted; then the standard form is converted to the original data.

• Business transactions messages. These include purchase orders, invoices, credit approvals, shipping notices, confirmations, and so on.

• Data formatting standards. Because EDI messages are repetitive, it makes sense to use formatting (coding) standards. In the United States and Canada, EDI data are formatted according to the ANSI X.12 standard. An international standard developed by the United Nations is called EDIFACT.

APPLICATIONS OF

TRADITIONAL EDI

LIMITATIONS OF

TRADITIONAL EDI

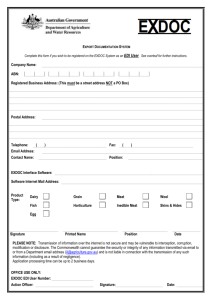

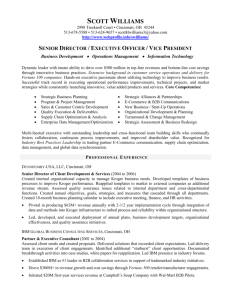

The Process of EDI.

The process of EDI (as compared with a non-EDI process) is shown in Figure T6.1. The figure shows that, in EDI, computers talk to computers. Messages are coded using the standards before they are transmitted using a converter. Then, the message travels over a value-added network (VAN) or the Internet

(secured). When received, the message is automatically translated into a business language.

Traditional EDI has changed the business landscape of many industries and large corporations. It is used extensively by large corporations, sometimes in a global network such as the one operated by General Electric Information System (which has over 100,000 corporate users). Well-known retailers such as Home Depot, ToysRUs, and Wal-Mart would operate very differently without EDI, because it is an integral and essential element of their business strategies. Thousands of global manufacturers, including Procter & Gamble, Levi Strauss, Toyota, and Unilever, have been using

EDI to redefine relationships with their customers through such practices as quickresponse retailing and just-in-time (JIT) manufacturing. These highly visible, highimpact applications of EDI by large companies have been extremely successful.

However, despite the tremendous impact of traditional EDI among industry leaders, the set of adopters represent only a small fraction of potential EDI users. In the

United States, where several million businesses participate in commerce every day, only about 100,000 companies have adopted traditional EDI. Furthermore, most of these companies have had only a small number of their business partners on EDI, mainly due to its high cost. Therefore, in reality, few businesses have benefited from traditional EDI.

Various factors held back more universal implementation of traditional EDI. For example, significant initial investment is needed, and ongoing operating costs are high

(due to use of expensive, private VANs). Another cost is the purchase of a converter, which is required to translate business transactions to EDI code. Other major issues for some companies relate to the fact that the traditional EDI system is inflexible.

For example, it is difficult to make quick changes, such as adding business partners, and a long startup period is needed. Further, business processes must sometimes be restructured to fit EDI requirements. Finally, multiple EDI standards exist, so one company may have to use several standards in order to communicate with different business partners. However, as some functions are automated into digital format, EDI is becoming simplified and easier to implement.

These factors suggest that traditional EDI—relying on formal transaction sets, translation software, and VANs—is not suitable as a long-term solution for most

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-202

W-202 Tutorial 6 Electronic Data Interchange, Extranets, XML, and Web Services

WITHOUT EDI

Start

P.O.

Deli v ery

Order Placer

Acco u nting/Finance Order Confirmation

Bill Deli v ery

Room

P u rchasing

Mail Room

Shipping

Recei v ing

Payment

Deli v ery

Prod u ct Deli v ery

Shipping

Sales

Acco u nting/Finance

Buyer

Standardized

P.O. Form

Start

Departmental

B u yer

EDI Con v erter

WITH EDI

Order F u lfillment

Seller

Comp u ter Con v erter

Generates

Standardized

P.O. Form

In v oice

Flash

Report

Instant

Data to

● Sales

● In v entory

● Man u fact u ring

● Engineering

INTERNET-BASED EDI

Recei v ing

Order F u lfillment

Prod u ct Deli v ery

Shipping

Buyer Seller

Figure T6.1

Comparing purchasing order (P.O.) fulfillment with and without EDI. ( Source:

Drawn by E. Turban.) corporations. Therefore, a better infrastructure was needed; Internet-based EDI is such an infrastructure.

Internet-based (or Web-based) EDI is becoming very popular (e.g., see Witte et al.,

2003). Let’s see why this is the case.

Why Internet-Based EDI?

When considered as a channel for EDI, the Internet appears to be a most feasible alternative to VANs for putting online B2B trading within reach of virtually any organization, large or small. There are a number of reasons for firms to create EDI ability over the Internet.

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-203

T6.1

Electronic Data Interchange (EDI) W-203

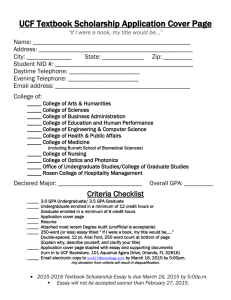

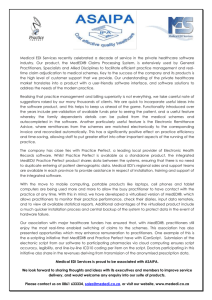

B u siness

Application

Translate

EDI

Formatting

Store and Forward

V al u e-Added

N et w ork

EDI

Formatting

Translate

B u siness

Application

TRADITIONAL ELECTRONIC DATA INTERCHANGE (EDI)

Figure T6.2

Traditional and

Web-based EDI. ( Source: Drawn by E. Turban.)

W e b Bro w ser

Internet

W e b

Ser v er

WEB-BASED EDI

EDI

Ser v er

Orders

In v entory

Legacy

Applications

• Accessibility. The Internet is a publicly accessible network with few geographical constraints. Its largest attribute, large-scale connectivity (without the need for any special company networking architecture), is a seedbed for growth of a vast range of business applications.

• Reach. The Internet’s global network connections offer the potential to reach the widest possible number of trading partners of any viable alternative currently available.

• Cost. The Internet’s communication cost can be 40 to 70 percent lower than that of VANs. Transmission of sensitive data can be made secure with a virtual private network (VPN; see Chapter 4 and Technology Guide 6).

• Use of Web technology. Using the Internet to exchange EDI transactions is consistent with the growing interest of business in delivering an ever-increasing variety of products and services via the Web. Internet-based EDI can complement or replace many current EDI applications.

• Ease of use. Internet tools such as browsers and search engines are very userfriendly, and most employees today know how to use them.

• Added functionalities. Internet-based EDI has several functionalities not provided by traditional EDI, which include collaboration, workflow, and search engine capabilities (see Boucher-Ferguson, 2002). A comparison between EDI and EDI/Internet is provided in Figure T6.2.

Types of Internet-Based EDI.

The Internet can support EDI in a variety of ways.

For example, Internet e-mail can be used to transport EDI messages in place of a

VAN. To this end, standards for encapsulating the messages within Secure Internet

Mail Extension (S/MIME) exist and need to be used. Another way to use the Internet for EDI is to create an extranet that enables a company’s trading partners to enter information into a Web form, the fields of which correspond to the fields in an EDI message or document.

Alternatively, companies can use a Web-based EDI hosting service in much the same way that companies rely on third parties to host their EC sites. Harbinger

Commerce (inovis.com) is an example of those companies that provide third-party hosting services.

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-204

W-204 Tutorial 6 Electronic Data Interchange, Extranets, XML, and Web Services

THE PROSPECTS OF

INTERNET-BASED EDI

GLOBAL

GLOBAL

OM

OM

OM

Many companies that used traditional EDI in the past have had a positive experience when they moved to Internet-based EDI. With traditional EDI, companies have to pay for network transport, translation, and routing of EDI messages into their legacy processing systems. The Internet serves as a cheaper alternative transport mechanism. The combination of the Web, XML, and Java makes EDI affordable even for small, infrequent transactions. Whereas EDI is not interactive, the Web and Java were designed specifically for interactivity as well as ease of use.

The following examples demonstrate the application range and benefits of

Internet-based EDI.

Example: Rapid Growth at CompuCom.

CompuCom Systems, a leading IT services provider, was averaging 5,000 transactions per month with traditional EDI. In just a short time after the transition to Web-based EDI, the company was able to average 35,000 transactions. The system helped the company to grow rapidly.

Example: Recruitment at Tradelink.

Tradelink of Hong Kong had a traditional

EDI that communicated with government agencies regarding export/import transactions, but was successful in recruiting only several hundred of the potential 70,000 companies to the traditional system. After switching to an Internet-based system,

Tradelink registered thousands of new companies to the system; hundreds were being added monthly, reaching about 18,000 by 2004.

Example: Better Collaboration at Atkins Carlyle.

Atkins Carlyle Corp., a wholesaler of industrial, electrical, and automotive parts, buys from 6,000 suppliers and has

12,000 customers in Australia. The large suppliers were using three different traditional EDI platforms. By moving to an Internet-based EDI, the company was able to collaborate with many more business partners, reducing the transaction cost by about $2 per message.

Note that many companies no longer refer to their IOSs as EDI. However, some

properties of EDI are embedded in new e-business initiatives such as collaborative commerce, extranets, Partner Relationship Management, and electronic exchanges.

The new generation of EDI/Internet is built around XML (see Section T6.3 and

Chapter 16).

T6.2

Extranets

Companies involved in an IOS need to be connected in a secure and effective manner and their applications must be integrated with each other. This can be done by using extranets, XML, and Web Services.

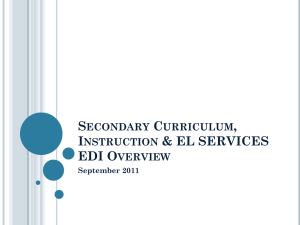

EXTRANETS In building IOSs, it is necessary to connect the internal systems of different business partners, which are usually connected to the partners’ corporate intranets. A common solution is to use an extranet. Extranets are generally understood to be networks that link business partners over the Internet by providing access to certain areas of each other’s corporate intranets. This arrangement is shown in Figure T6.3. (An exception to this definition is an extranet that offers individual customers or suppliers one-way access to a company’s intranet.) The term extranet comes from “extended intranet.”

The main goal of extranets is to foster collaboration between business partners.

An extranet is open to selected B2B suppliers, customers, and other business partners, who access it through the Internet. Extranets enable people who are located outside a company to work together with the company’s internally located employees. An extranet enables external business partners and telecommuting employees to enter the corporate intranet, via the Internet, to access data, place orders, check status, communicate, and collaborate. For an overview, see en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/Extranet/ and Wilkinson (2005).

The Components, Structure, and Benefits of Extranets.

An extranet uses the same basic infrastructure components as the Internet, including servers, TCP/IP pro-

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-205

Figure T6.3

The structure of an extranet. ( Source: Drawn by

E. Turban.)

T6.2

Extranets W-205

Intranets

Other

B u siness

Partners,

Go v ernment

Internet w ith V P N

My Company

Internet w ith V P N

Internet w ith V P N

My S u ppliers

A, B, C …

Intranets

My Field

Employees

Internet w ith V P N

Intranet

Intranet

B2B

My C u stomers

OM tocols, e-mail, and Web browsers. In addition, extranets use virtual private network

(VPN) technology to make communication over the Internet more secure. The

Internet-based extranet is far less costly than proprietary networks (VANs). It is a nonproprietary technical tool that can support the rapid evolution of electronic communication and commerce.

Why would a company allow a business partner access to its intranet? To answer this question, let’s look at Dr. Pepper in the following example.

Example: Dr. Pepper Notifies Bottlers of Price Changes.

Dr. Pepper/Seven Up, the $2 billion division of Cadbury Schweppes, uses an extranet to improve efficiency for its diverse community of 1,400 independent and franchise bottlers. The Bottler

Hub/Extranet is made available to Dr. Pepper’s entire group of registered bottlers and retailers. The extranet has helped automate the process of communicating price changes to retailers in real time.

Such automation was necessary for Dr. Pepper because the company depends on contract bottlers, who set the pricing of Dr. Pepper products in stores. Customer retailers such as Wal-Mart had complained about the bottlers’ practice of faxing weekly price changes. Because many bottlers were mom-and-pop organizations and did not have the resources to modernize the process, Dr. Pepper decided to put in an extranet-based centralized system that would make the pricing information available online, in real time, to retail outlets.

Dr. Pepper also uses its extranet for other purposes. In addition, the company collects sales data online, enabling merchants to report how many cases of soda they sell. The data are used to measure sales growth and to analyze brands and packages that are sold by a bottler to the major retail chains within a territory. The information is also used to help the national accounts department find opportunities to sell more Dr. Pepper/Seven Up brands within a particular account.

As seen in the example, the extranet enables effective and efficient real-time collaboration. It also enables partners to perform self-service activities such as checking the status of orders or inventory levels.

Types of Extranets.

Depending on the business partners involved and the purpose, there are three major types of extranets, as described here.

A Company and Its Dealers, Customers, or Suppliers.

Such an extranet is centered around one company. An example would be the FedEx extranet that allows customers to track the status of a package. To do so, customers use the Internet to access a database on the FedEx intranet. By enabling a customer to check the location

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-206

W-206 Tutorial 6 Electronic Data Interchange, Extranets, XML, and Web Services

Minicase T6.1

Dealer Connection Portal at Ford

Ford Motor Co. in Europe serves 7,500 dealers, speaking 15 different languages, in 18 countries. In order to connect them all, Ford created a portal, called DealerConnection. The portal provides dealers with a single point of real-time access to all of the information and tools they need to manage daily tasks efficiently, such as warranty checks and parts ordering.

It also frees dealers from having to access separate systems.

In addition, all information on pricing, products, servicing, customer services, and marketing is now available to the dealers online. Prior to the portal, updating dealers on new information often took five days for preparation, printing, and distribution of material; thus, the portal is achieving real efficiencies for Ford in its distribution of company information.

DealerConnection provides local dealers and Ford representatives in each country with control of their own

Enterprise Web application. Unlike traditional applications,

Enterprise Web applications, built on Plumtree ( plumtree.com) portal software, combine existing data and processes from enterprise systems with new shared services. These applications are managed within one administrative framework at the corporate level, allowing the company to create real, working

MKT GLOBAL online communities. DealerConnection also facilitates selfservice among dealers, allowing Ford to implement a more streamlined and centralized back office.

Instead of creating 18 different portals for the countries in which Ford operates, the company has developed one pan-

European portal with applications for each respective country and each line of business. By adopting this approach, Ford is empowering each country to create its own environment under the European umbrella of DealerConnection, even though Ford still has central control over its brand, image, and communications. The vendor believes that the portal has delivered a positive return of investment for both Ford and its network of dealers.

Source: Compiled from Plumtree Software Inc. (2003) (acquired by

BEA Systems in October 2005), and TelecommWorldWire (2003).

Questions for Minicase T6.1

1.

Why only one portal?

2.

What about the multilanguage and multicultural aspects?

3.

What are the benefits for Ford?

of a package, FedEx saves the cost of having a human operator do that task over the phone. Ford Motor is using an extranet-based portal with its dealers in Europe, as described in Minicase T6.1.

An Industry’s Extranet.

The major players in an industry may team up to create an extranet that will benefit all. The world’s largest industry-based, collaborative extranet is used by General Motors, Ford, and DaimlerChrysler. That extranet, called the Automotive Network Exchange (ANX), links the carmakers with more than

10,000 suppliers. The suppliers can then use a B2B marketplace, Covisint (covisint.

com, now a division of Compuware) located on ANX, to sell directly and efficiently to the carmakers, cutting communications costs by as much as 70 percent.

Joint Ventures and Other Business Partnerships.

In this type of extranet, the partners in a joint venture use the extranet as a vehicle for communications and collaboration. An example is Bank of America’s extranet for commercial loans. The partners involved in making such loans are a lender, loan broker, escrow company, title company, and others. The extranet connects lenders, loan applicants, and the loan organizer, Bank of America. A similar case is Lending Tree (lendingtree.com), a company that provides mortgage quotes for your home and also sells mortgages online, which uses an extranet for its business partners (e.g., the lenders).

Benefits of Extranets.

As extended versions of intranets, extranets offer benefits similar to those of intranets, as well as other benefits. The major benefits of extranets include faster processes and information flow, improved order entry and customer service, lower costs (e.g., for communications, travel, and administrative overhead), and overall improvement in business effectiveness.

Extranets are fairly permanent in nature, where all partners are known in advance. For on-demand relationships and one-time trades, companies can instead use B2B exchanges and hubs (Chapter 4) and directory services.

Two emerging technologies that are extremely important for IOSs are XML and

Web Services.

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-207

T6.4

Web Services W-207

T6.3

XML

An emerging technology that can be used effectively to integrate internal systems as well as systems of business partners is a language (and its variants) known as XML

(see Raisinghani, 2002); XML (eXtensible Markup Language) is a simplified version of a general data description language known as SGML (Standard Generalized

Markup Language). XML is used to improve compatibility between the disparate systems of business partners by defining the meaning of data in business documents.

XML is considered “extensible” because the markup symbols are unlimited and selfdefining. This new standard is promoted as a new platform for B2B and as a companion or even a possible replacement for EDI systems (see en.wikipedia.org/

wiki/XML). It has been formally recommended by the World Wide Web Consortium

(W3C.org).

XML Differs from HTML.

People sometimes wonder if XML and HTML are the same. The answer is, they are not. The purpose of HTML is to help build Web pages and display data on Web pages. The purpose of XML is to describe data and information. It does not say how the data will be displayed (which HTML does). XML can be used to send complex messages that include different files (and HTML cannot). See Technology Guide 2 for details.

Benefits of XML.

XML was created in an attempt to overcome limitations of EDI implementation. XML can overcome EDI barriers for three reasons:

1.

Flexibility. XML is a flexible language. Its flexibility allows new requirements and changes to be incorporated into messages, thus expanding the rigid ranges of

EDI.

2.

Understandability. XML message content can be easily read and understood by people using standard browsers. Thus, message recipients do not need EDI translators. This feature enables Small and Medium Enterprises to receive, understand, and act on XML-based messages.

3.

Less specialized. In order to implement EDI, it is necessary to have highly specialized knowledge of EDI methodology. Implementation of XML-based technologies requires less-specialized skills.

XML supports IOSs and makes B2B e-commerce a reality for many companies that were unable to use the traditional EDI. These and other benefits of XML are demonstrated in Minicase T6.2 and in Korolishin (2004). For more information, see xml.com.

Despite its many potential benefits, XML has, according to McKinsey Research

(Current Research Note, 2003), several serious limitations, especially when compared to EDI. These include lack of universal XML standards, lack of experience in XML implementation, and sometimes less security than EDI. However, this is rapidly changing and XML is being used more frequently.

Another technology that supports IOSs and uses XML in its core is Web Services.

T6.4

Web Services

As described in Chapter 2, Web Services are universal, prefabricated business process software modules, delivered over the Internet, that users can select and combine through almost any device, enabling disparate systems to share data and services.Web

Services can support IOSs by providing easy integration for different internal and external systems. (See Chapter 16 and Technology Guide 6 for technical details.) Such integration enables companies to develop new applications, as the following examples and minicases demonstrate.

Example: Web Services Facilitate Communication at Allstate.

The Allstate Financial

Group, with 41,000 employees and $29 billion in annual sales, used Microsoft.NET (a

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-208

W-208 Tutorial 6 Electronic Data Interchange, Extranets, XML, and Web Services

FIN OM

Web Services implementation) to create AccessAllstate.com (accessallstate.com). This

Web portal allows its 350,000 sales representatives to access information about Allstate investment, retirement, and insurance products.

Before the portal was developed, independent agents had to call Allstate customer service representatives for information, and transactions were done via mail, fax, or phone.The necessary information resided on five policy-management information systems running on mainframe computers—substantial technology investments that

Allstate was not willing to lose. But because Web Services enables easy communications between applications and systems, Allstate did not have to lose its mainframe investment. The agents use the Web portal to access the policy-management systems residing on the mainframe. Web Services make this connection seamless and transparent to the agents.

AccessAllstate.com has about 13,000 registered users and receives 500,000 hits per day. By unlocking the information on Allstate’s proprietary mainframes, the company increases revenues and reduces costs. The Web portal eliminates the need to call the service center to perform common account service tasks. Allstate estimates that the portal will pay for itself through lower call center and mailing costs. The company is also making all printed correspondence available online via the portal.

Sources: Compiled from Grimes (2003); and allstate.com (accessed June 2008).

Minicase T6.2

Fidelity Uses XML to Standardize Corporate Data

Fidelity Investments has made all of its corporate data XMLcompatible. The effort helped the world’s largest mutual fund company and online brokerage eliminate up to 75 percent of the hardware and software devoted to middle-tier processing, and speeded the delivery of new applications.

The decision to go to XML began when Fidelity developed its Powerstreet Web trading service. At the time, Fidelity determined it would need to offer its most active traders much faster response times than its existing brokerage systems allowed. The move to XML brought other benefits as well. For example, the company was able to link customers who have

401(k) pension plans, brokerage accounts, and IRAs under a common log-in. In the past, they required separate passwords.

Today, two-thirds of the hundreds of thousands of hourly online transactions at fidelity.com use XML to link the Web to back-end systems. Before XML, comparable transactions took many seconds longer because they had to go through a different proprietary data translation scheme for each back-end system from which they retrieved data.

ACC FIN

Fidelity’s XML strategy is critical to bringing new applications and services to customers faster than rivals. By using

XML as a common language into which all corporate data— from Web, database, transactional, and legacy systems—are translated, Fidelity is saving millions of dollars on infrastructure and development costs. Fidelity no longer has to develop translation methods for communications between the company’s many systems. XML also has made it possible for

Fidelity’s different databases—including Oracle for its customer account information and IBM’s DB2 for trading records—to respond to a single XML query.

Source: Compiled from “Fidelity Retrofits All Data . . .” (2001); and from fidelity.com.

Questions for Minicase T6.2

1.

Why did Fidelity decide to use XML?

2.

Why is it possible to develop applications faster with XML?

Minicase T6.3

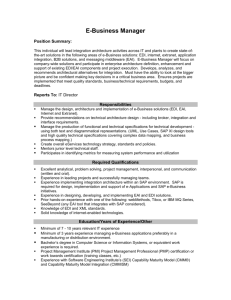

How Dell Is Using Web Services to Improve Its Supply Chain

The Problem

Dell Inc. ( dell.com) has many assembly plants. In these plants, located in various countries and locations, Dell makes PCs, servers, printers, and other computer hardware. The assembly plants rely on third-party logistics companies (3PLs), called

“vendor-managed hubs,” whose mission is to collect and maintain inventory of components from all of Dell’s component manufacturers (suppliers). The supply chain is shown in the attached figure.

In the past, Dell submitted a weekly demand schedule to the 3PLs, who prepared shipments of specific components to

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-209

S u ppliers—Man u fact u rers of Components

3PLs— V endor-Managed

H ub s

Dell ' s Assem b ly

Factory Plants

Minicase W-209

Dell’s supply chain. ( Source: Drawn by E. Turban.) the plants based on expected demand. Components management is critical to Dell’s success for various reasons:

Components become obsolete quickly, and their prices are constantly declining (by an average of 0.6 percent a week).

So the fewer components a company keeps in inventory, the lower its costs. In addition, lack of components prevents Dell from delivering its build-to-order computers on time. Finally, the costs of components make up about 70 percent of a computer’s cost, so managing components’ cost can have a major impact on the bottom line. Because it is expensive to carry, maintain, and handle inventories, it is tempting to reduce inventory levels as low as possible. However, some invento-

OM ries are necessary, both at the assembly plants and at the 3PLs’ premises. Without such inventories Dell cannot meet its “five-day ship to target” goal (computer must be on a shipper’s truck no later than five days after an order is received).

To minimize inventories, it is necessary to have considerable collaboration and coordination among all parties of the supply chain. For Dell, the supply chain includes hundreds of suppliers that are in many remote countries, speak different languages, and use different hardware and software platforms. Many have incompatible information systems that do not “talk” to Dell’s systems.

In the past, Dell suppliers operated with 45 days of lead time. (That is, the suppliers had 45 days to ship an order after it was received.) To keep production lines running, Dell had to carry 26 to 30 hours of buffer inventory at the assembly plants, and the 3PLs had to carry 6 to 10 days of inventory. To meet its delivery target, Dell created a 52-week demand forecast that was updated every week as a guide to its suppliers.

All of these inventory items amount to large costs (due to the millions of computers produced annually). Also, the lead time was too long.

The Solution

Dell started to issue updated manufacturing schedules for each assembly plant, every two hours. These schedules reflected the actual orders received during the previous two hours. The schedules list all of the required components, and they specify exactly when components need to be delivered, to which plant, and to what location of the plant (building number and exact door dock).These manufacturing schedules are published as Web Services and can be accessed by suppliers via Dell’s extranet. Then, the 3PLs have 90 minutes to pick, pack, and ship the required parts to the assembly plants.

Dell introduced another Web Services system that facilitates checking the reliability of the suppliers’ delivery schedules early enough in the process so that corrective actions can take place. Dell can, if necessary, temporarily change production plans to accommodate delivery difficulties of components.

The Results

As a result of the new systems, inventory levels at Dell’s assembly plants have been reduced from 30 hours to between 3 and 5 hours. This improvement represents a reduction of about 90 percent in the cost of keeping inventory. The ability to lower inventories also resulted in freeing up floor space that previously was used for storage. This space is now used for additional production lines, increasing factory utilization (capacity) by one-third.

The inventory levels at the 3PLs have also been reduced, by 10 to 40 percent, increasing profitability for all. The more effective coordination of supply-chain processes across enterprises has also resulted in cost reduction, more satisfied Dell customers (who get computers as promised), and less obsolescence of components (due to lower inventories). As a result,

turban_tutor06_W200-W210-hr 29-01-2009 11:30 Page W-210

W-210 Tutorial 6 Electronic Data Interchange, Extranets, XML, and Web Services

Dell and its partners have achieved a more accelerated rate of innovations, which provides competitive advantage.

Dell’s partners are also happy that the use of Web Services has required only minimal investment in new information systems.

Sources: Compiled from Hagel (2002), and from Dell.com, press releases (2000–2004).

Questions for Minicase T6.3

1.

What problems Dell did experience in its inventory management and the supply chain?

2.

How did Web Services correct the problems?

3.

What is the role of the 3PLs and how are they related to

Web Services?

References

Boucher-Ferguson, R., “A New Shipping Route (Web-EDI),” eWeek,

September 23, 2002.

Current Research Note, “The Truth about XML,” McKinsey Quarterly, 3,

2003.

Dell.com, press releases (2000–2004).

“Fidelity Retrofits All Data for XML,” InternetWeek, August 6, 2001.

Grimes, B., “Microsoft.NET Case Study: Allstate Financial Group,” PC

Magazine, March 25, 2003.

Hagel, J., III, Out of the Box. Boston: Harvard Business School Press, 2002.

Korolishin, J., “Industry-Specific XML Reduces Paperwork for C-store

Chain,” Stores, February 2004.

Plumtree Software Inc., “Food Connects European Dealer Network,”

plumtree.com, October 14, 2003.

Raisinghani, M. (ed.), Cases on Worldwide E-Commerce. Hershey, PA: The

Idea Group, 2002.

TelecomWorldWire, “Ford Deploys Pan-European Portal Using Plumtree

Technology,” October 15, 2003, encyclopedia.com/doc/1G1-

108888321.html (accessed July 2008).

Witte, C. L., M. Grünhagen, and R. L. Clarke, “The Integration of EDI and the Internet,” Information Systems Management, Fall 2003.

Wilkinson, P., Collaboration Technologies: The Extranet Evolution. Oxford,

UK: Taylor and Francis, 2005.