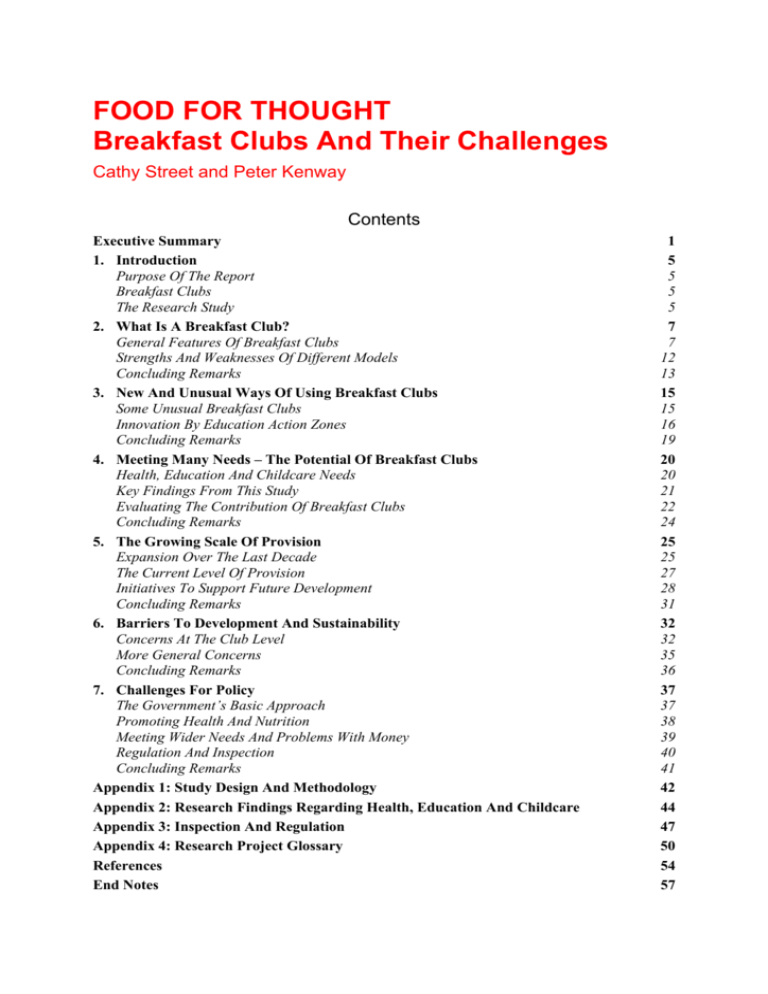

Breakfast clubs - New Policy Institute

advertisement