Providing voluntary services - Certified General Accountants of Ontario

advertisement

July 2005

Visit our website at:

www.cga-pdnet.org

Guidance Bulletin

for Practitioners

Providing voluntary services

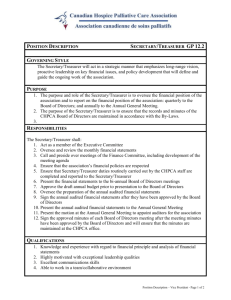

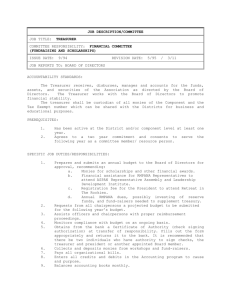

CGAs are well respected in the business community, a reputation that stems in part

from their willingness to contribute volunteer services to their communities. This

bulletin provides guidance to members who offer voluntary services by outlining

the differences between the various types of volunteer activities and your

professional responsibilities in relation to these.

Specifically, it is important to be able to differentiate between providing public

accounting services versus treasury services. It is also key that you understand your

role when serving on the board or governing body of an organization, whether for

profit or not-for-profit (for example, charities, professional associations,

condominium strata councils, day cares, community centres, clubs, and churches).

As a CGA, protecting the public interest is your paramount consideration. But you

should also be concerned about protecting yourself. The Association recommends

and at times requires members to consider and/or meet certain requirements when

engaged in voluntary services.

Types of volunteer services to not-for-profit

organizations

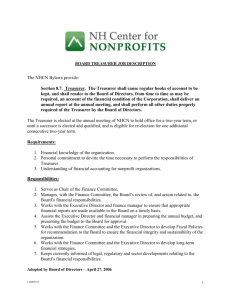

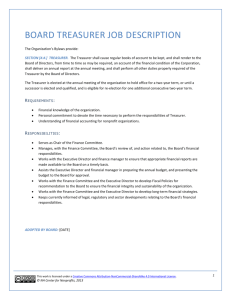

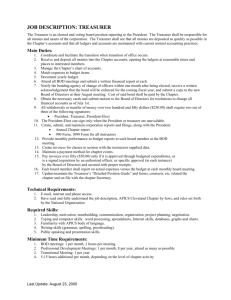

Treasurer services

Treasurer services are not considered public accounting, and therefore members

who are solely providing treasurer services on a volunteer basis are not required to

register in public practice with their Association.

A treasurer is considered an officer of an organization. All financial statements

issued by the treasurer should include a communication attached to the statement,

entitled Treasurer’s Report. It is not appropriate for the treasurer to issue any form

of third-party communication, such as an Audit or Review Engagement Report or a

Notice to Reader. If any form of third-party communication is attached to a

financial statement other than a Treasurer’s Report, the member providing treasurer

services is considered to be practising public accounting and may no longer serve as

treasurer for that organization.

The role of the treasurer in an organization is distinctly different from that of a

public accountant.

GUIDANCE BULLETIN FOR PRACTITIONERS

•

A treasurer is defined as “a person appointed to administer or manage the financial

assets and liabilities of a society, company or other body.”

•

A treasurer is an officer of the organization.

•

As stated above, a treasurer issues a Treasurer’s Report whereas a public

practitioner issues third-party communications attached to financial statements.

•

A treasurer does not act independently and is involved in management decisions of

an organization. For this reason, a treasurer is not able to perform audits or review

engagements for the organization.

•

The following are some of the duties that may be assigned to a treasurer:

preparation and approval of the financial statements and the corresponding

Treasurer’s Report

bookkeeping services

participation in management decisions

cheque signing

communication with auditors and coordination of the audit of the organization

{

{

{

{

{

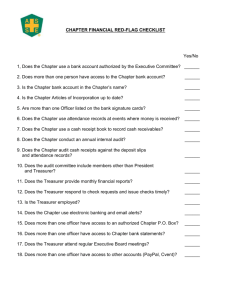

If you volunteer as a treasurer, you should ensure that the organization receiving your

services has sufficient directors and officers insurance, as well as errors and

omissions insurance. It is strongly recommended to confirm that adequate insurance

coverage exists before accepting a position on a Board. In particular, you should

review what activities or services might be excluded under the coverage.

Positions on a governing body

Members serving on a Board of Directors (the Board) or other governing body of an

organization are essentially acting as agents for the organization. The Board has been

given the power and duty to manage the affairs of the organization, and the directors

act on behalf of the organization. The Board is generally responsible for supervising

senior staff, providing strategic planning to the organization, and developing and

implementing corporate policy.

Traditionally, the position and honour associated with directorship on a Board has

helped to attract capable individuals. However, these are not the only attributes

attached to directorship. The law imposes a wide variety of duties and liabilities on

directors such that one needs to carefully consider the offer of a directorship position.

The liabilities to which directors are exposed have increased in recent years. This is

due in part to jurisprudence widening the exposure of directors to personal liability,

and also because of increased awareness of directors’ obligations. Members of the

organization and the public are now more prepared to hold directors accountable in

fulfilling such obligations.

A director’s role is to provide the best advice and expertise possible and to assist the

organization to succeed. The director’s job is to work for the benefit of the

organization and to make decisions and develop plans that will permit it to achieve

its objectives. A director uses his or her experience, business expertise, common

sense, and integrity to present and support ideas and decisions that they believe best

benefit the organization. Judgment needs to be applied in an unbiased and objective

manner. It is important that directors apply themselves diligently to the job they have

volunteered to perform.

By sitting on a Board, a director is instrumental in making a positive impact on

society, and members are encouraged to represent their professional designation in

Page 2 of 5

GUIDANCE BULLETIN FOR PRACTITIONERS

their community. However, one must realize that a director on a Board assumes

liability and faces possible exposure to personal financial loss. Directors may be held

personally liable in the following situations.

•

•

•

•

Directors enter into a contract without proper authorization, or on behalf of a nonexistent corporation.

The director’s own actions are tortuous.

Directors breach their fiduciary duty (i.e., fail to act in the best interests of the

corporation, to be loyal and honest, and to act in good faith).

Directors fail to meet the numerous statutory obligations imposed on them under

federal and provincial legislation.

There are several reasons to ensure that an organization has adequate directors and

officers insurance coverage before accepting a position on a Board. Without adequate

coverage, an organization may not be able to protect its directors in their roles. It is

also important for members to note that professional accountants may be held

disproportionably liable for financial issues of an organization due to the degree of

reliance that the Board may place on their professional designation.

Directors and officers insurance policies typically protect against claims arising out

of Board decisions or omissions, or out of actions or activities performed directly

under the auspices of the Board. There are as many different kinds of directors and

officers insurance policies as there are insurance companies. Typically, these policies

protect directors and officers for the following:

•

•

damages which they become legally obligated to pay and for which the

organization cannot or will not pay

claims made against a director or officer whom the organization is obligated to

indemnify

Since there are varying types of insurance policies, a prospective director should also

confirm the type and extent of insurance coverage of the organization before agreeing

to sit on the Board.

How can you protect yourself as a director and officer?

•

Know why you are there. Review your interest in the organization and make sure

you are able to serve it to the best of your ability without a conflict of interest.

Above all, make sure you are qualified to sit on the Board.

•

Review the bylaws of the organization. Make sure these bylaws are as strong, fair,

and supportive of the directors and officers as possible. Specifically, review the

indemnification provisions of these bylaws.

•

Be familiar with the legislative act regulating your activities and the organization

being served, such as the Society Act, Corporations Act, or Condominium Act.

•

Research and do your homework. Know what you are talking about. Understand

the strategic direction of the organization and its goals and objectives. Be prepared

to assist the organization to achieve these to the best of your ability.

•

Ask questions. Do not take things for granted and make sure you understand all

the issues discussed at meetings. Always question items that cause you

uncertainty.

•

Attend meetings and educate yourself about the organization’s mandate and all

aspects of its operations to ensure you are knowledgeable and ready to make

informed decisions affecting the organization.

Page 3 of 5

GUIDANCE BULLETIN FOR PRACTITIONERS

•

Exercise independent judgment when voting for all corporate decisions.

•

Make sure that the Board has access to outside professional expertise and use it if

unsure of a direction or position taken by the organization.

•

Review the organization’s financial statements. Question problems, deal with

them, and make sure they are resolved.

•

Keep pace with current legal trends. Be aware of litigation that affects

corporations and organizations and how it may possibly affect you in your

capacity as a director.

•

Ensure that the organization has appropriate and sufficient errors and omissions

insurance.

Public accounting services

Members are often approached by not-for-profit organizations to volunteer their

services without remuneration or honorarium. While the Association encourages and

commends taking an active role in local communities through volunteer activities,

members are cautioned to ensure they have the experience and skills to conduct the

engagement.

When considering providing public accounting services to not-for-profit

organizations on a volunteer basis, members should first contact the Association.

You will be required to register in public practice and must obtain errors and

omissions insurance coverage. The good news is that coverage under the CGACanada Professional Liability Insurance is free when providing volunteer public

accounting services to not-for profit organizations. Attention should be paid to what

services are excluded under the coverage.

Members must also comply with the rules of professional practice contained in

section 500 of the CGA Code of Ethical Principles and Rules of Conduct (CEPROC).

Depending on the Association, practice reviews and education requirements may also

be required.

When providing voluntary public accounting services, members must adhere to

professional standards in the conduct of such engagements. Professional standards

include the standards, principles, and practices generally accepted by the profession

that apply to accounting, financial reporting, assurance and non-assurance

engagements, and related services. CGA-Canada’s Public Practice Manual provides

guidance, including sample letters and checklists, and the Accounting and Assurance

Handbooks establish recommendations covering many of these standards, principles,

and practices. You should also be familiar with other rules in CEPROC that apply.

These include Rule R201 – Confidentiality, Rule R202 – Independence, Rule R301 –

Competence, and Rule R305 – Terms of Engagement.

Conclusion

Members find that volunteering their time and professional expertise with an

organization can be both rewarding and satisfying. However, before accepting a

professional engagement or appointment to a Board, you must ensure that you have

both the resources and technical expertise to provide the service and that there is

appropriate and adequate insurance. Also, before volunteering, you should contact

your Association to obtain additional information, complete necessary

documentation, and take advantage of the resources available.

Page 4 of 5

GUIDANCE BULLETIN FOR PRACTITIONERS

References

CGA Code of Ethical Principles and Rules of Conduct: Rules R201, R202, R301, R304,

R305

CGA Independence Standard

CGA-Canada Public Practice Manual

CICA Handbooks, Assurance and Accounting

Page 5 of 5