Filofax – Sticking to the Paper Planner

advertisement

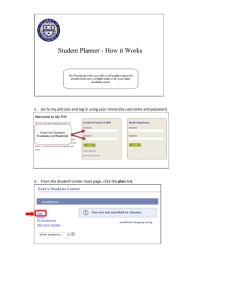

Filofax – Sticking to the Paper Planner A Story of Graceful Retreat Chris Carrillo, Joungwook Choi, Sarah Kabacinski, Jongkil Shin, Dennis Zhang Day Planning: From Paper to Electronic In today’s over-agendized world, it is hard to go without some sort of day planner. Whether it’s Microsoft Outlook, Blackberry, or the plain old ring-bound paper planner, the day planner has infiltrated our daily lives. While the dominant format appears to be electronic, the paper planner has managed to survive this hi-tech movement. In fact, one company that has refused to retrench and move into electronic planning is Filofax, the original paper planner company. Filofax got its start in 1921, by Norman and Hill, Ltd., in London1. The company was built on the discovery of an American organizing system by an Englishman during World War I. This system had been previously used by engineers and scientists2. What began as a small business, servicing military and clergy, became the market leader by the 1980’s, when paper planners became standard personal items3. During this time period, many competitors showed up on the scene, including Franklin Covey, which made a similar leather ring-bound day planner. Soon thereafter, electronic organizers began to enter the market, threatening to obliterate the paper planner. First came the Personal Information Manager (PIM), which due to compatibility issues with other PIMs and PCs and poor functionality, did not prove to be much of a threat to paper planners4. Next, the PIM was pushed out by PDAs, followed by network enabled PDAs, such as the Blackberry and iPhone. It may seem that there is no longer a place for Filofax on the map of personal organization, yet the company has survived by doing what it has always done—ring-bound paper planning. Filofax has managed to carve out a niche market, and is optimistic that it will continue to thrive by targeting emerging markets. The company views itself as an aspirational brand, with the belief that, “we can get there”5. The Day Planner Industry: Five Forces Analysis Before examining Filofax, we think it is helpful to look at the day planner industry in general. A five forces analysis will highlight Filofax’s relative strength in the paper day planner market. Starting with supplier power, stationary manufacturers have been faced with rising costs for raw materials, such as pulp and paper, metals, plastics, and adhesives6. Growth in demand from developing economies, particularly China and India, coupled with rising gas, electricity, and fuel may force suppliers to pass on these costs to Filofax7. However, Filofax is less vulnerable to these price increases due to its high mark-up and loyal customer base. Buyers have relatively low bargaining power due to the high switching costs of the planner itself, which can cost as much as $500. Filofax can charge a premium for its products because of its reputation and differentiated product. For example, Filofax sells a variety of customized inserts and software that reformats Microsoft Excel spreadsheets, Word documents and PowerPoint presentations to fit into a Filofax binder8. The inserts also require frequent replacement, which allows Filofax to benefit from the razor and blade model9. Threat of entry is a moderate risk. Filofax’s competitive advantage is the value of its brand and the up-market appeal. It also benefits from access to distribution channels, which over the years have included Harrod’s, Harvey Nichols and Fortnum and Mason in England as well as high-end department stores Neiman Marcus, Saks Fifth Avenue and Bloomingdale’s in the United States10. However, capital requirements for paper planners are relatively low and since Filofax caters to a niche market, it doesn’t benefit from economies of scale or absolute cost advantages. In fact, there are several generic imitators and only one major rival in the form of the Franklin Covey planner. Like Filofax, Franklin Covey sells a specialized planning system and the associated binders and inserts. This key competitor also benefits from distribution through its brick and mortar Franklin Covey stores. The greatest risk for Filofax is the threat of substitutes for paper planners. Some experts believe that markets have diverged into paper and electronic and believe that PDAs and Blackberries are used more for wireless connectivity than as true organizers11. Filofax appeals to the paper traditionalists, who prefer writing things down, fear the loss of data on electronic devices, or feel that using an electronic device is too laborious12. However, as PDAs, Smartphones, and Blackberries become more affordable, gain more features, and have a more intuitive interface, traditional paper customers may be more willing to adopt these new devices. Setting the Scene: Filofax Chooses Paper Over Electronic As an essential yuppie accoutrement, Filofax grew aggressively in the 1980’s, doubling sales almost every year. However, by the end of the 1980’s, the yuppie culture steadily declined and Filofax lost its cultural iconic status. At roughly the same time, electronic organizers emerged and started to gain favor with many Filofax users. By the early 1990’s, PC electronic organizer software and PDAs became the new fad with sales of electronic organizers in the millions. Facing a completely changed market environment, Filofax was overextended, and the rapid expansion throughout the 1980’s started to strain the company’s financials. Losses started to mount and the company’s stock plummeted. The impact of this harsh business environment was disastrous and eventually caused to the company to sell control to an investment group that brought in a new management team. New Chief Executive Robin Field chose to fight in the old market, firmly believing that there would be life for Filofax after the yuppie era, even in the face of increasing threats from electronic organizers. He felt that with some discipline, Filofax could be just as successful in the 1990’s as it was in the 1980’s13. The Rationale: Why Stick to the Paper Planner? Field recognized that the billion-dollar worldwide market for personal organizers, calendars, address book pages and other fillers was still growing at around 20% per year in dollar terms. Additionally, he felt that the paper planner’s “razor and blade” business model was both attractive and sustainable. Customers buy the binder, and then come back year after year to buy the fillers, providing a recurring revenue stream and a steady customer base. By sticking with its core competence, Field signaled that he didn’t view electronic organizers as a competitive threat. In his opinion, electronic devices were taking over functions previously performed on a computer rather than with a personal organizer and a pen. Back to Basics To implement his vision, Field took a number of steps to turn around Filofax, including streamlining product lines, expanding into the US and continental Europe, and making selective acquisitions in related market segments14. He first pared down the swollen product lines from over 1,000 to around 100, tossing out all the product lines that were not generating steady revenue. He then cut prices of basic Filofax organizers by more than half when it was clear that consumers were looking more for value than price-tag prestige. To improve margins, Field outsourced costly and time consuming processes such as warehousing. Collectively, these measures helped grow sales and expand margins. Field then focused on expanding into new markets, especially the $300 million U.S. personal organizer market. Since this market was dominated by low cost competitors that sell for far less than Filofax, Field decided to focus on the high end market, choosing to sell to Saks Fifth Avenue, Bergdorf Goodman and Neiman Marcus. Essentially, Filofax created a market for itself. As cash flows improved, Filofax was able to make selective acquisitions, not in the emerging electronic organizer market, but in market segments closely related to its existing products, such as pen and pencil makers, and less expensive personal organizers. These acquisitions strengthened Filofax’s foothold in the old fashioned paper and pencil based personal organizer market. Battling the Electronic Threat: Identifying New Markets In most ways, PDAs perfectly replaced all functions of the paper planner. PDAs had calendars, telephone directories, and memo pads. However, for normal use in daily life, the Filofax had a significant competitive advantage against high-tech electronic organizers; flexibility. Filofax allows users to take notes and schedule appointments whenever they want. For example, users can schedule time to watch a television program or record the number of daily calories consumed anywhere in the Filofax15. In contrast, a PDA doesn’t always provide this kind of flexibility since there are rules for data input coupled with required network connectivity to manage schedules and notes. Many users also found that typing hundreds of phone numbers and viewing data on small screens was both frustrating and difficult. One group, found to be very sensitive to this issue, was women with children trying to juggle both a career and their children’s hectic schedules16. In fact, woman now account for approximately 60% of Filofax planner sales17. As time went on, additional segments abandoned PDAs to return to the familiarity of Filofax planners. Older users, disillusioned by the keyboard and small buttons, preferred the simple functionality of Filofax to the unnecessary and excessive functions of PDAs and PCs18. Even those who preferred the technological superiority of Blackberries were reacquainted with Filofax when some companies, worried about employee addiction to Blackberries, banned the use of Blackberries and converted to Filofax19. With the success of the US and UK market, Filofax expanded into other European countries and emerging markets like Russia, where the use of organizers, paper or electronic, has been unpopular. In these countries, Filofax successfully developed the paper planner market by educating users on the importance of time management. In emerging markets, premium goods became far more aspirational and Filofax’s leather organizer became a premium item serving the fashion-conscious female group. A Changing Market and Graceful Retreat Entering the 1990’s, despite the increasing threat of fancy digital gadgets, many firmly believed that the fundamental demand for paper planners would somehow thrive. Based on this belief, four different leadership regimes took turns and tried out their own formula to unlock the changing demand patterns of the past 28 years, hoping to ultimately find the favorable equilibrium between paper and electronic substitutes. When an investor group took over Filofax in 1990, the company was losing more than $3M in income due to overexpansion. The new management team was confident, however, that Filofax’s strong brand would turn the company around with time. They were right. With help of the growing market, the company returned to profitability soon after the acquisition20. During the latter part of the 1990’s, however, the market started to reshape with the flood of digital devices. Management was stunned to see that even the most loyal customers were exploring new digital planners. This signaled that management needed a new approach to address this traditional segment. As revenues started to decline, so did management’s confidence. Day Runner paid $51M to take over the company in 1998. This US based paper planner maker saw this as a great opportunity for the expansion they needed in the European market. Before long, however, Day Runner also ran into financial difficulties as its existing business was feeling pressure from the rapidly growing electronic handheld market21. As a result, the company had to cut 130 jobs by closing down two UK based Filofax factories. Even though Filofax business alone was profitable, the company defaulted on a $61M loan in December 200022. The Letts Group, from the UK, took the next shot at Filofax. Letts bought Filofax Group in 2001 for $29.7M to form a company with combined revenue of £55M and 550 people covering nine international locations23. Unlike the preceding management team, Letts seemed to understand the right approach to this changing market. By 2006, global sales of Filofax had soared 20% to $65.8M. From 2003, revenues of the combined Letts Filofax Group grew at a 5% rate annual with 12% compounded margin improvement (see the graph below). Letts Filofax Revenue and Operating Margin Trend 120 16.0% 110 14.0% 100 90 12.0% 80 10.0% 70 60 8.0% 2003 2004 2005 Op Margin 2006 2007 Revenue Source: Hoovers’ Online Pro Currently, Letts Filofax is owned by a private equity firm called Phoenix Equity Partners who bought the company in March 2006 in a £45 million leveraged buyout. Future Outlook Having survived the rise of digital competition, Filofax now aims to build on its success by acquiring new opportunities with its current private equity owner’s investment expertise. In addition, the company is planning on leveraging its existing distribution network to aggressively push such regions as Russia, the Baltic, and the Middle East. During the transition period, it has successfully changed its target customers from a predominantly male to female demographic, and it is now aiming to expand in terms of geography. Along with heavy investment in the paper front, Letts Filofax is also exploring ways to utilize digital advancement in the market for its own good. Sources: 1 “History of the Personal Data Assistant (PDA).” BBC. (2004, March 31). <http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A2284229> 2 Filofax Limited. 2008. <http://www.filofaxusa.com/aboutus/heritage.asp> 3 Filofax Limited. 2008. <http://www.filofaxusa.com/aboutus/heritage.asp> 4 “History of the Personal Data Assistant (PDA).” BBC. (2004, March 31). <http://www.bbc.co.uk/dna/h2g2/A2284229> 5 Kate Norton (2006, December 12). Filofax’s Paper Power, BusinessWeek 6 Business Editors (2008, Jun.26)Research and Markets; Stationary Market Report 2008, Business Wire 7 Business Editors (2008, Jun.26)Research and Markets; Stationary Market Report 2008, Business Wire 8 Kate Norton (2006, December 12). Filofax’s Paper Power, BusinessWeek 9 Richard W. Stevenson (1995, Dec. 29) Filofax, 80’s Tailsman, Thrives in Too-busy 90’s, New York Times 10 Steve Lohr (1987, Apr. 8) Organizing Pays Off At Filofax, New York Times 11 Kate Norton (2006, December 12). Filofax’s Paper Power, BusinessWeek 12 Demorris Lee (2004, Jan. 4) Paper calendars, not pocket PCs, choice of many, Raleigh News & Observer 13 Richard W. Stevenson, (1995, Dec. 29) Filofax, 80’s Tailsman, Thrives in Too-busy 90’s, New York Times 14 Richard W. Stevenson, (1995, Dec. 29) Filofax, 80’s Tailsman, Thrives in Too-busy 90’s, New York Times 15 Edward Rothstein, (1990, Jul.19) Electronice Notebook; Organizers: Chip vs. Paper, New York Times 16 Richard W. Stevenson, (1995, Dec. 29) Filofax, 80’s Tailsman, Thrives in Too-busy 90’s, New York Times 17 Kate Norton (2006, December 12). Filofax’s Paper Power, BusinessWeek 18 Demorris Lee, (2004, Jan. 3) Paper Calendars, not pocket PCs, choice of many, Raleigh News & Observer 19 Northern Advocate, (2006, Oct. 2) Workaholics risking Blackberry addition, APN New Zealand Ltd. 20 Richard W. Stevenson (1995, December 29). Filofax, 80's Talisman, Thrives in Too-Busy 90's, NY Times 21 Cameron Simpson (2001, February 16). Future looks blank for failing Filofax, The Herald 22 Factiva (2001, January 22). Profitable Filofax for sale to ease Day Runner Finance, Printing World 23 Fay Schopen (2001, August 2). Letts buys Filofax business for $17M, Print Week