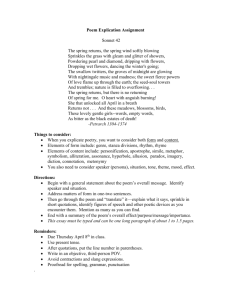

Assorted poems for critical analysis 1

advertisement

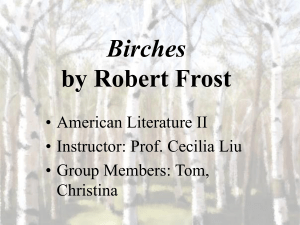

Birches BY ROBERT FROST When I see birches bend to left and right Across the lines of straighter darker trees, I like to think some boy's been swinging them. But swinging doesn't bend them down to stay As ice-storms do. Often you must have seen them Loaded with ice a sunny winter morning After a rain. They click upon themselves As the breeze rises, and turn many-colored As the stir cracks and crazes their enamel. Soon the sun's warmth makes them shed crystal shells Shattering and avalanching on the snow-crust— Such heaps of broken glass to sweep away You'd think the inner dome of heaven had fallen. They are dragged to the withered bracken by the load, And they seem not to break; though once they are bowed So low for long, they never right themselves: You may see their trunks arching in the woods Years afterwards, trailing their leaves on the ground Like girls on hands and knees that throw their hair Before them over their heads to dry in the sun. But I was going to say when Truth broke in With all her matter-of-fact about the ice-storm I should prefer to have some boy bend them As he went out and in to fetch the cows— Some boy too far from town to learn baseball, Whose only play was what he found himself, Summer or winter, and could play alone. One by one he subdued his father's trees By riding them down over and over again Until he took the stiffness out of them, And not one but hung limp, not one was left For him to conquer. He learned all there was To learn about not launching out too soon And so not carrying the tree away Clear to the ground. He always kept his poise To the top branches, climbing carefully With the same pains you use to fill a cup Up to the brim, and even above the brim. Then he flung outward, feet first, with a swish, Kicking his way down through the air to the ground. So was I once myself a swinger of birches. And so I dream of going back to be. It's when I'm weary of considerations, And life is too much like a pathless wood Where your face burns and tickles with the cobwebs Broken across it, and one eye is weeping From a twig's having lashed across it open. I'd like to get away from earth awhile And then come back to it and begin over. May no fate willfully misunderstand me And half grant what I wish and snatch me away Not to return. Earth's the right place for love: I don't know where it's likely to go better. I'd like to go by climbing a birch tree, And climb black branches up a snow-white trunk Toward heaven, till the tree could bear no more, But dipped its top and set me down again. That would be good both going and coming back. One could do worse than be a swinger of birches. 1. First Response: What do you think the swinging of birches symbolizes? Why? 2. Why does the speaker in this poem prefer the birches to have been bent by boys instead of ice storms? 3. How is “Earth” described in the poem? Why does the speaker choose it over “heaven” (line 56)? 4. Find at least two precise words to describe the poem’s tone. Is there a shift in this poem? If so, where is it? How does the shift affect the tone? 5. If you were asked to write an essay response for this poem about how Frost uses poetic devices to deliver his overall meaning (theme) in the poem, which would you choose. Briefly outline your plan below. Those Winter Sundays Robert Hayden, 1913 - 1980 Sundays too my father got up early and put his clothes on in the blueblack cold, then with cracked hands that ached from labor in the weekday weather made banked fires blaze. No one ever thanked him. I’d wake and hear the cold splintering, breaking. When the rooms were warm, he’d call, and slowly I would rise and dress, fearing the chronic angers of that house, Speaking indifferently to him, who had driven out the cold and polished my good shoes as well. What did I know, what did I know of love’s austere and lonely offices? 1. As you read, you may have noticed that the poem doesn’t use a masculine pronoun; hence, the voice could be a woman’s. Which do you think it is? Does the gender of the voice make any difference to your reading? Would it make any difference about which details are included or which language is used? 2. Does the father’s point of view appear anywhere in the poem? Do we ever know what he is thinking or feeling? 3. Why is so much of the poem about coldness and warmth? How do these things affect the poem’s meaning? 4. In what sense do you think the word “offices” is being used in the last line? 5. If you had to sum up this poem’s deeper meaning / purpose in one sentence, what would that be? The Red Hat It started before Christmas. Now our son officially walks to school alone. Semi-alone, it's accurate to say: I or his father track him on the way. He walks up on the east side of West End, we walk on the west side. Glances can extend (and do) across the street; not eye contact. Already ties are feelings and not fact. Straus Park is where these parallel paths part; he goes alone from there. The watcher's heart stretches, elastic in its love and fear, toward him as we see him disappear, striding briskly. Where two weeks ago, holding a hand, he'd dawdle, dreamy, slow, he now is hustled forward by the pull of something far more powerful than school. The mornings we turn back to are no more than forty minutes longer than before, but they feel vastly different-flimsy, strange, wavering in the eddies of this change, empty, unanchored, perilously light since the red hat vanished from our sight. Rachel Hadas (b. 1948) 1. What emotions do the parents experience throughout the poem? How do you think the boy feels? How do enjambment and end stop help create meaning in the poem? 2. What is it that “pull(s) the boy along in lines 15-16? 3. Why do you think Hadas titled the poem “The Red Hat” rather than, for example, “Paths Part” (line 9)? To a Daughter Leaving Home By Linda Pastan (born 1932) When I taught you at eight to ride a bicycle, loping along beside you as you wobbled away on two round wheels, my own mouth rounding in surprise when you pulled ahead down the curved path of the park, I kept waiting for the thud of your crash as I sprinted to catch up, while you grew smaller, more breakable with distance, pumping, pumping for your life, screaming with laughter, the hair flapping behind you like a handkerchief waving goodbye. 1. Comment on the appropriateness of the extended metaphor as a means of creating the theme for this poem. What other extended metaphors do you think would work just as well to convey the same theme? 2. Compare the themes in Pastan’s poem and in Rachel Hadas’s “The Red Hat.” HOW does each poet deliver her meaning?