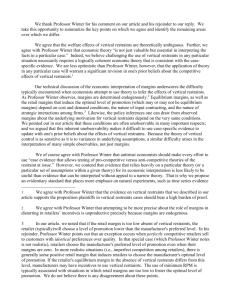

Vertical restraints – an economic perspective

advertisement