Peevyhouse v. Garland Coal & Mining Co.

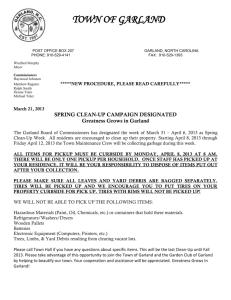

advertisement