1. National accounting. Consider the following U.S. data from 2010

advertisement

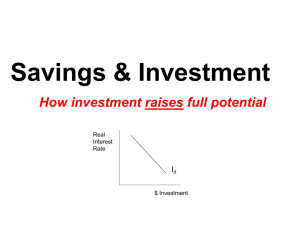

1. National accounting. Consider the following U.S. data from 2010: ($ in billions) 10,348 3,001 1,756 2,816 Personal consumption expenditure Government expenditure Investment expenditure Private saving (a) Define Gross Domestic Product (GDP). Gross Domestic Product (GDP): value of all final goods and services produced by an economy (usually a country) during a certain period of time (usually a year).1 (b) Calculate GDP, national saving, public saving, and disposable income. 1. GDP equals = + + = 10 348 + 3 001 + 1 756 = 15 105 billion. 2. We know that, in a closed economy, national savings equal investment; thus, national saving equals $1,756 billion. 3. We also know that national saving equals private plus public savings; therefore public saving equals 1 756 − 2 816 = −1 060; i.e., the US government is running a deficit of $1.06 trillion. 4. To calculate disposable income first we need to calculate taxes: −1060 = − = − 3 001 = −1 060 + 3 001 = 1 941 Then disposable income equals − = 15 105 − 1 941 = 13 164 2. Money. (a) Define the nominal interest rate and the real interest rate. The nominal interest rate is the cost of borrowing (and return to saving) in nominal terms. The real interest rest is the cost of borrowing (and return to saving) in real terms; it is the price at which consumption (purchasing) power is transferred across time. (b) In 1979 the nominal interest rate on three-month Treasury bills averaged 10 percent, and the GDP deflator rose from 50.88 to 55.22. We need to use the GDP deflator to calculate the inflation rate = ∆ 5522 − 5088 = = 85% 5088 Since the real interest rate equals the nominal minus (expected) inflation = − = 10 − 85 = 15% approximating expected by realized inflation. 3. Money. (a) Define inflation (deflation) rate. The increase (decrease) in the overall level of prices expressed as a ratio (usually a percentage) of the initial price level. 1 Definitions in the textbook are equivalent (valid as well). 1 (b) Why do many economists think that the consumer price index overstates the true rate of inflation? There are two reasons why the CPI exaggerates inflation: 1. It fails to adjust for improvements in quality: a 2014 car may be more expensive than a 2000 car was (in real terms) but it is a better car, not the same car. Some price increases may reflect improvements in quality and may not be due to a generalized increase in the price level. 2. It does not take into account commodity substitution by consumers. If the price of beef shoots up, consumers would eat chicken or pork since we need meat, not beef. But, if what it shows in the CPI basket is beef, this particular price increase would be taking as an example of a generalized increase in the price level. 4. Public budget. On February 11 Finance Minister Jim Flaherty forecasted a $2.9-billion deficit for 2014-15. The following table shows the Federal budget forecast for 2014-2015 as announced by the Finance Minister: Revenue and expenditures ($ billion) Revenue Emergency fund Expenses Federal debt Debt-to-GDP ratio 276.3 3.0 276.2 619.9 32.0 (a) Define and calculate the (official) deficit or surplus. Does your calculations agree with Mr Flaherty’s? Explain. Official deficit or surplus: a shortfall or excess of revenue over expenditure, including interest payments. The forecasted official deficit equals 2762 − 2763 = −01billion or a surplus of $100 million. The discrepancy between this number and Mr Flaherty’s is due to the inclusion of the fund in expenses but, technically speaking, this is not an expenditure. (b) Define the primary deficit or surplus. Can you calculate it or do you need more information? If so, which information do you need? Primary (program) deficit or surplus: a shortfall or excess of revenue over program or primary expenditure (expenditure other than interest payments). It cannot be calculated because we need to know interest payments which we cannot calculate, even knowing the extent of Federal Debt, because we do not know the interest rate. 5. The closed economy in the long run. Suppose that the government decides to reduce taxes. In the model used in chapter 3, determine the effects this will have on aggregate output, consumption, private saving, public saving, national saving, investment, and the interest rate? (Your answer should include both a graph and a written argument.) (a) Aggregate output does not change since in the long run (in equilibrium) is determined only by the availability of factors of production and the state of technology, = ( ) (b) A reduction in taxes increases disposable income ( − ) and, thus, consumption, = ( − ), by ∗ ∆ where refers to the Marginal Propensity to Consume. (c) Likewise, a reduction in taxes increases private saving by ∗ ∆ = (1 − ) ∗ ∆ where refers to the Marginal Propensity to Save. (d) A reduction in taxes decreases public saving, − , by ∆ (e) A reduction in taxes decreases national savings = − ( + ) since it increases private consumption. Since National saving equals public plus private savings, public savings decrease by ∆ and private savings increase by ∗ ∆ ∆ the net effect is negative. 2 (f) Since in a closed economy in equilibrium I = S. investment decreases. (g) In the loanable funds market, savings equals the supply of loanable funds. At the old interest rate there is excess demand of loanable funds and pressure on interest rates to increase: investors bid for the now scarce funds. Other way of thinking of this: if the government spending is not funded by taxes. the government needs; to borrow and compete with private investors for scarce funds. LI jI 3