Change Management in Healthcare

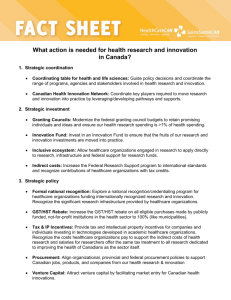

advertisement