ABSTRACT Title of Document - DRUM

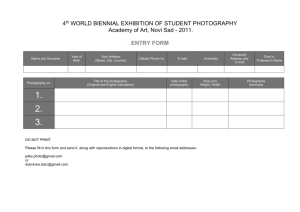

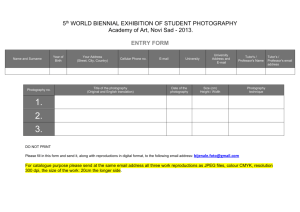

advertisement