Means of Mitigating The Effects of Sex

advertisement

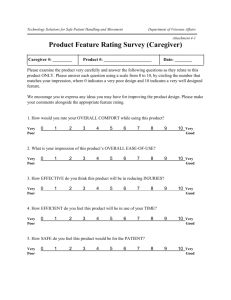

Impression Management: Means of Mitigating The Effects of Sex-Stereotyping In Organizations by Runuka Hodigere Diana Bilimoria WP-10-05 Copyright Department of Organizational Behavior Weatherhead School of Management Case Western Reserve University Cleveland OH 44106-7235 e-mail: ler6@case.edu IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT: MEANS OF MITIGATING THE EFFECTS OF SEX-STEREOTYPING IN ORGANIZATIONS Renuka Hodigere Diana Bilimoria Department of Organizational Behavior Case Western Reserve University Cleveland, OH. Page 1 of 34 1 2 Impression management: Means of mitigating the effects of sex-stereotyping in organizations 3 4 Abstract 5 Sex-stereotyping is a major barrier to advancement of women in organizations. Since sex- 6 stereotypes are based on role attribution, they are less amenable to change through measures 7 such as legislation and education. Women need to strategically manage the roles attributed to 8 them such that they are reflective of their roles in the organization, rather than that of a 9 generalized notion of women. Adoption of such measures, over time will bring about a 10 reconfiguration of perceptions about women in organizations and make it easier for women to 11 embrace their multiple roles and identities more effectively. 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 Page 2 of 34 32 INTRODUCTION 33 The United States Bureau of Labor Statistics indicates that in 2008 there were fewer than 34 3 million women in managerial positions, of which only 6.5% reached chief executive level. 35 These data are disheartening. While this indicates an improvement over the past, it is still a very 36 small proportion when compared to the still relatively small total population of less than 16 37 million women in management roles. Although there was only a 2% difference in the numbers of 38 female and male general managers, there are twice as many male CEOs as female. 39 Women’s success in overcoming entry barriers suggests that the threshold requirements 40 of education, skills and commitment have been met. Yet, their inability to overcome 41 organizational barriers to progress indicates that there are issues that still need to be addressed. 42 One of the reasons given for paucity of women in critical roles and higher positions in such roles 43 is sex-stereotyping (Davies-Netzley, 1998; Oakley, 2000). Sex-stereotyping is the super- 44 imposition of generalized notions about women on to the role-identity of individual women. This 45 implies that women, regardless of the roles played by them in the workplace, are perceived 46 primarily by a generalized stereotype of women. Such stereotypes could range from that of a 47 nurturer to a sex-object. The attributes attendant to these sex-stereotypes have been shown to be 48 persistently contrary to the attributes, perceived by the majority, to be required in career 49 professionals (Schein, 1973; 1996; 2007), and women continue to be particularly disadvantaged 50 by such stereotyping (Ryan & Haslam, 2007; Hopkins O’Neil & Bilimoria, 2006). Consequently, 51 it is essential for women to manage the perceptions that are held by pertinent others in the 52 organizational context. Such management includes creating the “right” images, and managing 53 extant perceptions to resonate with these right images. Impression management is the array of 54 behaviors; verbal and non-verbal, by which women can accomplish this objective. Page 3 of 34 55 Much of the literature on gender-discrimination has focused on alleviating the problem 56 either at a system level through policy and legislation or at the individual level by focusing on 57 educating or penalizing a perpetrator. But, studies of gender discrimination also show that 58 discriminating acts can be very subtle and hard to identify as being discriminatory rather than 59 benign. It can thus be surmised that while legislation, education and penalty are essential to 60 mitigating the problem of gender discrimination, transformation of the stereotype associated with 61 the sex is an important element of the change process. As I will draw out in the section on sex- 62 stereotyping, it is also an area in which women can take control of the situation and feel 63 empowered by playing an active part in the mitigation of discrimination against them. It is my 64 contention that impression management is that approach to containing the influence of sex- 65 stereotyping. 66 Ironically, impression management has largely been constructed as a “falsification” tool 67 used to deceive others and protect oneself against unfavorable projection by others (Deluga, 68 1991; see Bolino, Kacmar, Turnley & Gilstrap, 2008 for review). However, a study of the roots 69 of impression management from social role theory (Hartley & Hartley, 1952) 70 presentation (Goffman, 1959) shows that the genesis of impression management was based on 71 principles of influence through self-monitoring and strategic presentation. Therefore, at its 72 source, impression management is a means of creating images that resonate with the contextual 73 roles played by individuals. Much of recent literature on impression management is focused on 74 its use in organizational contexts such as interviews, performance reviews, crises, or the 75 ubiquitous handling of supervisors (Elsbach & Sutton, 1992; Stevens & Kristof, 1995; Kacmar & 76 Carlson, 1999; Singh & Vinnicombe, 2001; Bolino, Varela, Bande & Turnley, 2006). However, 77 there have been no studies that explore the application of impression management in mitigating to self- Page 4 of 34 78 the subtle yet intensely pervasive problem of stereotyping in organizations. Given that 79 stereotyping as a construct is too large to be examined in any depth in one study, I have restricted 80 this paper to drawing some theoretical conclusions about sex-stereotyping alone, particularly 81 with respect to women in organizations. 82 The few studies that link women and impression management are about gendered 83 differences in the use of impression management in organizations (e.g. Singh, Kumra & 84 Vinnicombe, 2002; Guadagno & Cialdini, 2007). Overall, these studies have established that 85 women perceive the notion of impression management negatively. Some of the respondents in 86 these studies admitted to losing organizational battles to colleagues who managed their image 87 perceivably better than the women respondents. Less studied are use of impression management 88 by potential victims of sex-stereotyping and the influence of such strategies on their career. 89 The present theoretical exploration offers a means by which women can exercise some 90 control over their career advancement through strategically amplifying contextually appropriate 91 behaviors. Contrary to typical perception, impression management is applied in this study to 92 minimize the application and strength of negative stereotypical perceptions; and not for self- 93 promotion. I propose that application of negative stereotypes can be minimized by replacing the 94 negative stereotypes with positive stereotypes that resonate with the changing realities of women 95 in organizations. I refer to this process as stereotype transformation because a stereotype vacuum 96 is not a plausible option. Stereotyping is a useful mechanism, necessary for managing complex 97 sets of information. The focus of my study is the replacement of an erroneous stereotype with 98 one that resonates more accurately with the current reality about women in organizations and the 99 implications of such transformation on organizational norms. The female professional in an 100 organizational set up should be perceived as professional first as that is her primary role in that Page 5 of 34 101 situation. The outcome corresponding to such a perception is greater equity in recruitment, 102 compensation and career advancement. Therefore, the stereotype I seek to create is that of a 103 professional characterized by her functional expertise and personal ability supplemented by the 104 quality of communality, fairness and fortitude that characterize her as a woman. 105 Through this discourse, I hope that the utility of impression management in alleviating 106 the effects of stereotyping on women’s career progression in male-dominated professions will 107 receive attention. I begin with an elaboration of the concept of sex-stereotyping and a summary 108 of the existing literature on the major stereotypes held about women and the ways in which sex- 109 stereotyping affects women in organizations. The theoretical foundation of impression 110 management and its application in the workplace is the second part of the paper. Finally, I 111 develop a theoretical model of the role of impression management in mitigating sex-stereotyping 112 in organizations finally resulting in a change in organizational norms. 113 SEX-STEREOTYPING AS A BARRIER TO CAREER ADVANCEMENT 114 There is universal agreement on the fact that women’s careers generally do not advance 115 on par with equivalent men’s careers. One of the causes forwarded to explain this lag is 116 discrimination based on sex-stereotyping. Stereotypical assumptions about women, based on 117 their sex and corresponding attribution of social role are that they lack the attributes required in 118 managers (Heilman, Block & Martell, 1995; Hopkins, O’Neil & Bilimoria, 2006); attributes 119 required in managers being those demonstrated by men (Schein, 2007). Just as men who chose to 120 be home-makers are likened to women or attributed with feminine characteristics. Hence, it is 121 prudent to acknowledge the basis of sex-stereotyping while staying grounded in the mission of 122 creating a stereotype of managers that is more gender-neutral and thus inclusive. Page 6 of 34 123 Sex-stereotyping creates strong barriers to the career advancement of women in several 124 ways. The first is an entry barrier to certain roles that are argued to be more suitable to men than 125 women. Sex-segregation literature reveals that such barricaded positions are typically those that 126 are more central to the operations of the organization; involve handling of important resources, 127 involving visibility to and perhaps interaction with those who hold power in the organization 128 (Oakley, 2000; Furst & Reeves, 2008). Consequently, women get herded into roles that are 129 peripheral to the business, have little scope for influence and visibility. Barriers are also erected 130 in such a way that it is hard to distinguish discrimination from benevolent sexism (Benokraitis, 131 1997). 132 Another way in which women are dissuaded from aspiring to penetrate male bastions is 133 more insidious and less covert. Women receive lower evaluations on both performance and 134 potential (Eagly, Karau & Makhijani, 1995; Eagly, Makhijani & Klonsky, 1992). Lower 135 evaluations are justified by either setting lower standards in goals or misattributing the cause of 136 performance. Being devalued in this way consistently can lead to sufficient demotivation among 137 women that they either become disengaged with the process of career advancement or seek a 138 different environment. This has been shown in studies where career paths of men and women 139 have been found to be disparate on advancement processes (O’Neil, Hopkins & Bilimoria, 2008). 140 Women tend to ascend the organizational ladder by moving to other organizations at significant 141 rungs in the ladder, while men ascend to similar positions with the same organization (Cox & 142 Harquail, 1991). To have to move to a different organization at each significant level may result 143 in women taking longer to reach the same position as their equivalent male colleagues. 144 A third way in which sex-stereotyping contributes to deceleration in women’s careers is 145 through misguided assumptions about women’s life-choice preferences. As illustrated by the Page 7 of 34 146 famous investigation at Deloitte and Touche (McCracken, 2000), male supervisors make 147 stereotypical assumptions about women employees, which on verification may more often than 148 not prove to be erroneous. Women are assumed to have an immutable preference for home and 149 family to work aspirations. Changing demographics are evidence that this is not a universal truth. 150 Just as there are women who prefer to either build their lives around their families or subordinate 151 their careers to the needs of the family; there are women who choose to privilege their career 152 ambitions. Such sex-stereotyping prevails even in highly intellectual and sophisticated 153 organizations. 154 Based on the above discussion, the perceived gaps in the identity of women as 155 professionals are most profound in the areas of ability, effectiveness and commitment. It is on 156 these three grounds that women are significantly disadvantaged by existing sex-stereotypes. 157 Ability 158 Masculine jobs in organizations are line jobs, not only due to demographic dominance by 159 men but also the associations with greater power, resources and criticality to the organization 160 (Ragins & Sundstrom, 1989; Lyness & Heilman, 2006). Women in line positions present a 161 higher incongruence than women in staff jobs. Therefore, it is stereotypically assumed that 162 women lack the ability required of the job. From the interview stage, women are held at a 163 disadvantage as both male and female interviewers tend to rate women lower than men for 164 ‘masculine’ roles or positions with male subordinates (Rose & Andiappan, 1978). Consequently, 165 they receive less support in organizations for opportunities to demonstrate their ability. Studies 166 have shown that women in sex-role congruent jobs received higher evaluations than those in sex- 167 role incongruent jobs (staff vs. line), women in line jobs had to achieve higher evaluations than 168 men to be promoted (Lyness & Heilman, 2006). In situations where women do demonstrate the Page 8 of 34 169 ability to succeed, the counter-stereotypical outcome is distorted through attributions like 170 external help, to resonate with the stereotype (Greenhaus & Parasuraman, 1993). The tendency 171 of women to attribute successes to external factors may allow them to participate in such 172 distortions. Evaluations of behavior also lend themselves readily to stereotypical assumptions. 173 Studies have shown that in the absence of irrevocable evidence, information will be more readily 174 distorted to align with stereotypical assumptions (Nieva & Gutek, 1980). As organizations move 175 from mere task evaluation to task and behavioral evaluations, such assumptions have greater 176 implications for women employees. Persistent devaluation of performance on the basis of 177 subjective evaluation criteria may lead to a loss of valence for the outcomes associated with such 178 evaluations. 179 Effectiveness 180 Women have been shown to manage and lead through a more democratic and communal 181 leadership style than men (Eagly & Johnson, 1990). This has been commonly attributed to sex- 182 role socialization. As has been discussed, women managers who adopt masculine styles 183 successfully are found to be more negatively evaluated than feminine, successful women 184 (Heilman, Wallen, Fuchs & Tamkins, 2004). Yet, women are required to display agentic 185 qualities in order to be considered suitable for positions of greater responsibility. In order to 186 manage this dissonance, women are forced to adopt a conciliatory management style in order to 187 maintain harmony in the work group and also a task orientation in order to be considered 188 effective (Ragins & Sundstrom, 1989; Eagly, Makhijani & Klonsky, 1992). Despite this, it was 189 found that women in masculine roles were found less effective than their male counterparts 190 (Eagly, Karau & Makhijani, 1995; Oakley, 2000). Further, jobs in organizations are becoming 191 more inter-dependent, with implications for personal resourcefulness. Women have been found Page 9 of 34 192 to be lacking in networking abilities (Van Emmerik, 2006) which could be inferred as inability to 193 perform interdependent tasks effectively. Several studies have shown that women build relational 194 networks rather than instrumental (Ibarra, 1992; 1993; Burke, Bristor & Rothstein, 1995). Such 195 apparent difficulties of women have been stereotyped as their inability to be resourceful and 196 hence effective in the organizational context. 197 Commitment 198 Given the biological and attending psychological characteristics of women, it is 199 inevitable that child-bearing and rearing will form a large part of the life aspirations of a majority 200 of women. Or at least that is a popular perception residing at the core of stereotypical 201 assumptions about women. Perhaps a more subliminal basis of this assumption is the need for 202 men to propagate their race (Sidanius & Veniegas, 2000). The proportion of working women has 203 been consistently increasing yet the impending transition to this role is at the root of the 204 stereotypical assumption that women do not have a long-term commitment to their careers. A 205 corollary to this assumption is that even if commitment to the career is intact, it will still be 206 secondary to the commitment to family. This greatly harms the probability of success for those 207 women who are both high on potential and commitment to their careers (Jerdee & Rosen, 1976). 208 The direction of research thus far has been to describe the systemic shortcomings that 209 have constrained women from achieving success in organizations. Systemic shortcomings have 210 by definition originated in the ‘other’: males dominating the organization and the systems in 211 organization, which are created for the males in the organization. While this perspective has been 212 deeply explored and several measures taken to counter it, by way of legislation and activism to 213 increase the number of women in organizations; very little has been done to explore the other Page 10 of 34 214 side of the situation, namely the role of women in the situation. Therefore, it is essential to 215 recognize that while systemic shortcomings persist, women can also acknowledge their role in 216 the creation and propagation of stereotypes. Such acknowledgement will create the space for 217 women to participate in transforming the organizational landscape to better suit the changing 218 demographics of women. 219 Role of women in the perpetuation of sex-stereotyping 220 Stereotypes are shared perceptions of characteristics common to a group (Tajfel & 221 Forgas, 2000). Inferences about people from behaviors to traits underlie development and 222 maintenance of stereotypes (Gawronski, 2003). By definition, stereotypes are perceptions and as 223 such the perceived also has a role in the creation of stereotypes (Stangor & Schaller, 2000). 224 Therefore, if there are certain stereotypical assumptions made about women, such have a basis in 225 observed behavior of women. Women in organizations have been found to be uncomfortable at 226 initiating negotiations (Walters, Stulmacher & Meyer, 1998; Small, Gelfand, Babcock & 227 Gettman, 2007) and directing action (Eagly, Karau & Makhijani, 1995). Women have been 228 found to hesitant to apply their expertise, relying on relational influences to lead and direct 229 (Eagly & Johnson, 1990). The inability of women to leverage networks and collegial relations 230 has also been a significant contributor to the persistence of the stereotype that women are not 231 resourceful (Bierema, 2005). Perhaps the greatest yet rather subtle reason that men have been 232 able to penalize counter-stereotypic behavior has been the perception of lack of confidence 233 among women in their ability and suitability (Eagly & Johnson, 1990, Hopkins, O’Neil & 234 Bilimoria, 2006). Page 11 of 34 235 While such self-effacing qualities may be advantageous to them in other arenas, in 236 organizations they lead to self-propagating cycles of low-confidence, lack of progress and 237 resignation to status quo (Ragins & Sundstrom, 1989). Women who do have the confidence in 238 their ability may be constrained by other factors such as geographical restrictions and economic 239 needs. Therefore women operate under two types of constraints: their professional identity and 240 social identity. Yet women have managed these dual roles successfully for over four decades at 241 least. Despite this, they continue to face barriers on these bases. One of the reasons for this could 242 be that they have been successful because they were successful at hiding how they managed the 243 dual roles (Singh, Kumra & Vinnicombe, 2002). They have managed to portray the most 244 appropriate images at each level and overcome barriers of perception. This absence of 245 communication has resulted in the mutation of the organizational woman into the organizational 246 man, rather than a celebration of the organizational woman. While this may have been a 247 successful strategy for token women, as numbers increase it is becoming imperative that the 248 mould of the organizational woman be created. A significant task in this endeavor is a recast of 249 stereotypes about women in organizations. 250 In order to create a more egalitarian environment, where women do not have to suffer 251 negative consequences no matter what they do (Eagly, 2007), they need to take greater control of 252 the perceptions projected upon them. Women have to consistently monitor the interaction 253 between their professional-role and sex-role identities to avoid perceptual biases. Impression 254 management is one such avenue of creating definitions of role-identities and interactions within 255 the contextual framework of organizations. 256 In the introduction, I advanced the idea that women who seek career advancement may 257 be able to reduce the negative effects of sex-stereotyping using impression management. I also Page 12 of 34 258 proposed that while the popular understanding of impression management is falsification; there 259 is another aspect to impression management that has hitherto not been explored in the context of 260 stereotype management in organizations. The next section presents my perspective on impression 261 management, which is both positive and transformative. The last section will elaborate on the 262 model of transformation of stereotypes as applied in the context of women seeking career 263 advancement in organizations. 264 IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT 265 Impression management is the array of behavior – verbal and non-verbal, used to control 266 information, to influence the perception of others about us and their behavior towards us 267 (Rosenfeld, Giacalone & Riordan, 1995). As such impression management is a composite of 268 both “what” and “how” (Goffman, 1959) e.g. a handshake itself conveys adherence to the social 269 norms of greeting and the quality of the handshake is perceived as an indicator of the quality of 270 the person. 271 and synchronized to convey a consistent image (Tedeschi, Bonoma & Schlenker, 1972; 272 Tedeschi, 1981). The process by which one consciously and deliberately manages this interaction 273 in order to project the pertinent self is called impression management (Schlenker, 1980). Communicating an impression requires that both layers of behavior be controlled 274 Impression management is composed of two parts: impression motivation and 275 construction (Leary & Kowalski, 1990). The motivation to manage the impressions one creates is 276 based on the salience of projecting certain impressions of oneself, expectancy of success at 277 attaining the desired outcomes, and perceived distance between desired and current image 278 (Schlenker, 1980; Leary & Kowalski, 1990; Singh & Vinnicombe, 2001; Roberts, 2005). This is 279 particularly relevant for women in organizations as correcting stereotypical assumptions will Page 13 of 34 280 have an impact on outcomes distorted by their application. The impression of a professional is 281 not restricted to one incident or audience, it a stable impression across situations and audiences 282 in one context, the organization (Tedeschi & Melburg, 1984; Wayne & Liden, 1995; Roberts, 283 2005). Therefore, creating and maintaining a professional image is an exercise in projection as 284 represented in Figure 1. 285 Insert Figure 1 about here 286 287 Strategic self-presentation is a pattern of self-presentation intended to maximize approval 288 and minimize disapproval (Doherty & Schlenker, 1991). For women in organizations, this would 289 mean enhancing those attributes that contribute to their success. At the same time, it is also 290 important that such attribution is not clouded over by the qualities that make them successful 291 professionals. This is an important distinction, as this is often used as a basis for sex-stereotyping 292 (Greenhaus & Parasuraman, 1993). A woman who attains success in a business project, who 293 tends to portray her relational qualities in success rather than expertise or effort, is creating space 294 for misattribution of the source of her success. Therefore, strategic self-presentation is focusing 295 on those professional qualities that contributed to her success. This is different from self- 296 enhancement behavior such as praising oneself or boasting about one’s accomplishments. 297 Strategic self-presentation is a shift in focus from the attributes that would get attention such as 298 being lucky or being able to get help based on relational equations to professional expertise 299 applied to the problem at hand. Focusing on the “professional” attributes that contributed to their 300 success such as expertise and influence in the organization will enable them to counter the 301 barrier of misattribution. Page 14 of 34 302 Particularly for the organizational woman, it is important to manage the perception of her 303 actions such that they are attributed to the correct bases ability and expertise in the professional 304 function, rather than those directed by stereotypes such as communality and supplication. 305 Consequently, it is reasonable to believe that women in organizations who manage the 306 impressions they convey, such that the focus is success and not the “woman” behind the success, 307 are perceived as more congruent to the stereotype of a successful professional than those who do 308 not. 309 MEANS OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT 310 Women have been found to be averse to using impression management tactics (Singh & 311 Vinnicombe, 2001; Guadagno & Cialdini, 2007), probably based on the characteristics of artifice 312 and deviousness associated with it. Taking such aversion into account, I suggest three impression 313 management methods that can be considered compliant with the self-concept of women which 314 also promote their image as professionals rather than female professionals. The three methods 315 are exemplification, ingratiation and demonstration. Exemplification and ingratiation are 316 maneuvers defined by Jones and Pittman (1982) and demonstrative impression management was 317 discussed by Bolino et. al. (2008) as other-focused impression management tactics. Women tend 318 to prefer protective methods of impression management to acquisitive; even the acquisitive 319 methods they engage in tend to be defensive rather than directive (See Guadagno & Cialdini, 320 2007 for review). Therefore, the methods I have focused on are other-focused but directive so 321 that they may be more acceptable than using methods that call for a radical change of mindset. 322 Methods as I refer to them are commonly called impression management tactics. Because 323 I believe that they are stable and continual processes of impression creation and reinforcement, I Page 15 of 34 324 offer them as positive behavioral methods rather than as Machiavellian attempts to deceive. It is 325 also my hope that the examples I provide in the next section will not be taken as prescriptions of 326 behavior. My intention is to offer them as illustrations, as methods lend themselves to adaptation. 327 Recognizing that it is ridiculous to propose that all women behave alike, I offer a theory of 328 behavior and hope that women may adapt it to their own aspirations and self-identities to create 329 an image that resonates with what they wish to accomplish. The next section clarifies the 330 impression management methods that can work towards reducing negative sex-role stereotypes 331 attached to women in organizations. 332 Exemplification 333 Exemplification is defined by Jones and Pittman (1982) as demonstrating exemplary 334 behavior through integrity and self-sacrifice, that is worthy of being emulated by others. 335 Volunteering for tough assignments and going beyond the call of duty are some of the behaviors 336 associated with exemplification. Exemplification also overlaps with the concept of altruism in 337 the literature on organizational citizenship behavior (Bolino, 1999). Altruism and exemplary 338 behavior have a gendered construction given their strong correspondence with the idea of 339 communality. In OCB literature, altruism is found to not reap as great rewards for women as for 340 men due to the expectancy of communality among women (Kidder & Parks, 2001). Similarly, 341 unless positioned strategically as befitting the notion of impression management, exemplary 342 behavior can be misconstrued as either stereotypical of women or invite backlash for being 343 martyr-like behavior (Harris, Kacmar, Zivnuska & Shaw, 2007). Therefore, women need to 344 redefine exemplification to meet their needs of highlighting altruistic behavior while ensuring 345 that it is not attributed to communality. Page 16 of 34 346 The fact that it was beyond the call of duty or involved sacrifice should be brought into 347 focus such that there is some degree of reciprocity attached to it. Women are said to lack 348 commitment to their careers because they do not stay in office longer and build network ties with 349 their colleagues. While, staying long hours at work and creating social ties with colleagues are 350 seen as necessities for career advancement (Moore, 1990), women can take advantage of their 351 exemplary behavior to build the same networks by not conceding that such behavior is an 352 attribute of their gender. Exemplary behavior should be used to highlight their commitment to 353 their career as opposed to building merely relational networks. Women should also ensure that 354 exemplary behavior is construed as effort expended towards career progress and not just creating 355 impressions of favorability, as they have generally been wont to do (Lewis & Neighbors, 2005). 356 Ingratiation 357 Doing favors for others to be liked is the definition of ingratiation. According to 358 impression management research, ingratiation is a precursor to achievement of a self-serving 359 motive (Jones & Pittman, 1982). Therefore, ingratiation in its completeness could be defined as 360 doing favors for others, to be liked, in order that such favors can be reciprocated by others. This 361 fact, when supplemented by the other fact that almost no organizational function can be 362 accomplished by one person in isolation of other members of the organizations, renders 363 ingratiation a necessity. Effectiveness is a notion that gains credibility only when shared by a 364 supervisor and subordinates, if any. Hence, ingratiation is an integral component of effectiveness 365 perceptions (Eagly, Karau & Makhijani, 1995). 366 However, as with any other impression management method, ingratiation bears with it 367 the risk of misinterpretation if not conveyed strategically. Particularly, in the case of women, Page 17 of 34 368 ingratiation can be easily misconstrued as supplication. In order to avoid such misunderstanding, 369 ingratiation can be conveyed by ways other than doing favors. They can take the form of 370 genuinely extending a helping hand, without sacrificing self-interest, based on a promise of 371 reciprocity. It can take the form of building professional friendship based on mutual professional 372 goals. Providing confirmation of a colleague’s output in front of a supervisor when necessary can 373 also be conveyed as ingratiation, when such action is conveyed to the colleague in question. 374 Building such credits will ensure that examples of one’s effectiveness are supported and 375 supplemented. Supervisors tend to rate women who are liked by their colleagues more favorably 376 regardless of actual performance. Colleagues support female colleagues who are effective and 377 supportive, rather than just effective. Communality in women can be thus played to their own 378 advantage rather than being a barrier to advancement. This can be achieved by managing the 379 impression of being communal with that of being effective, to project the image of effectiveness 380 to a wider audience. 381 Demonstration 382 Though not a widely studied means of impression management, it is relevant to the 383 problem of mitigating sex-stereotyping, as it refers to a demonstration of knowledge about the 384 organization. Having established their trustworthiness through exemplification and ingratiation 385 methods discussed above, women can create a new image of themselves as holders of 386 information. Research shows men to be strategic and women to be communal (See Eagly and 387 Wood, 1991 for a review). However, the communality of women can be pursued to their 388 advantage, in creating channels of information from disparate sources. Women who are able to 389 tap their social networks both within and outside their organization for information will be able Page 18 of 34 390 to gain positions of strength. Demonstration of an ability to not just collect information but use it 391 strategically to inform supervisor’s and team’s decisions will improve their professional image 392 and credibility in the team. Such an improvement can lead directly to creating impression of 393 ability that has eluded women thus far (Lyness & Thompson, 1997). 394 Above I have depicted a few scenarios in which impression management can be put to 395 use to create context-appropriate perceptions. As roles change and the resource-available varies 396 correspondingly, more strategies also become available. With the passage of time, I anticipate 397 that a stereotype that is accurate today may become invalid. Neither stereotypes nor society are 398 static entities, therefore it is important to understand the bases of my propositions regarding the 399 role of impression management in social reconfiguration. 400 Having elaborated on a few means of impression management, I feel that it is important 401 to reiterate one of the biggest advantages of impression management: it allows for individualistic 402 application. There is no prototype of the right impression or the right way of managing 403 impressions. It is however possible to engage in circumspection in the manner of self- 404 presentation so that irrelevant information and behaviors do not overshadow relevant 405 contribution. Consequently, women in organizations should see that it is not necessary for them 406 to portray one specific kind of behavior to be perceived as professionals; just as not all successful 407 men in organizations are aggressive or ambitious. One of the significant outcomes of such a 408 realization will be the individual adaptation of impression management methods by women 409 regardless of the level or function they occupy in organizations. It is hoped that by portraying the 410 image of eligibility for success, such women will pave the way for future generations of women 411 to be perceived not from the lens of stereotypes of women in general but that of qualified women 412 capable of success. Therefore, my model is based on the belief that not only can professional Page 19 of 34 413 women change the stereotypes applied to them individually but through persistence, they can 414 also change the stereotypes about professional women as a collective image in society. Such a 415 transformation of stereotypes should contribute towards supplementing legal measures taken to 416 mitigate the effects of sex-stereotyping in organizations. 417 A MODEL OF STEREOTYPE TRANSFORMATION THROUGH IMPRESSION 418 MANAGEMENT 419 The premise of my model is that individual women practicing impression management to 420 create individual impressions of successful professional will contribute to the creation of the new 421 stereotype of a successful professional. This step of transforming individual impression into a 422 collective perception regarding the collective of women in organizations will be achieved 423 through the process of reflexivity. The theoretical foundation of my model of stereotype 424 transformation and elaboration of the model is presented in the next section. 425 Reflexivity 426 If one considers an organization is a microcosm of society, then the concept of reflexivity 427 as advanced by Giddens (1984) in his theory of structuration provides a means by which 428 individual action, when performed by sufficient numbers of individuals can result in 429 transformation of norms. 430 According to structuration theory there is a recursive relationship between social 431 structures and individuals. This phenomenon is termed reflexivity. Reflexivity is the means 432 through with individuals and groups interact recursively to create norms and structures within the 433 societal framework. In this way “rationalizations of actions [are] chronically involved in the 434 structuration of social practices” (Giddens, 1984: 26), are perpetuating social systems by the Page 20 of 34 435 production and reproduction of action in the enactment of everyday social life. It was his belief 436 that it is not only social structures that act on individuals but individual actions influence the 437 creation of social structures. Taking social identity enactment and structuration in conjunction, it 438 can be reasonably ventured that the manner in which social identities are enacted can influence 439 the stereotypes that prevail in society. Hence, enacting social identities strategically with the 440 intent of creating a stereotype that is more resonant with reality can be instrumental in the 441 transformation of stereotypes. Hence I advance the proposition that impression management, 442 practiced by a sub-group of sufficient numbers will result in a transformation of the stereotypes 443 attributed to them, through the process of reflexivity. 444 Model of change for mitigating the effects of sex-stereotyping 445 Transformation of stereotypes, even within a smaller structure such as an organization is 446 a function of time and participants. The model of transformation of stereotypes also has certain 447 boundary conditions: consistency, and authenticity. In brief, assuming that individual women 448 approach interactions in the organizations through the framework of impression management, 449 both authentically and consistently; over time, if enough number of women participate, there will 450 be a transformation in the stereotype of women in an organization. The objective towards which 451 this model is geared is a change in organizational norms such that they correspond with systemic 452 efforts like equal opportunity, pay and growth (See Figure 2). 453 Insert Figure 2 about here 454 455 There are four parts to the model: existing sex stereotypes, impression management, 456 effects of impression management on existing stereotypes and expected outcome from Page 21 of 34 457 impression management. A basic operationalization of the model is that when impression 458 management acts on existing sex stereotypes, it could result in either maintenance or change in 459 stereotype. A change in stereotype should ultimately lead to a change in organizational norms of 460 behavior towards professional women. 461 To begin with, stereotypes may be either strongly or weakly held by individuals. 462 Stereotypes that are more deeply entrenched are naturally correspondingly more resistant to 463 change efforts. On the other hand, stereotypes that are not very strongly believed in are open to 464 transformation upon receiving disconfirming evidence (Stangor & Schaller, 2000). Strong 465 stereotypes however offer a greater challenge in terms of transformation. Greater consistency 466 and persistence will be required to being about a change in strongly held stereotypes as 467 compared to weaker stereotypes. 468 Impression management will provide a direct avenue for weak existing stereotypes to be 469 transformed into a new and more resonant stereotype of professional women. Women who 470 encounter strong stereotypes that are deeply etched in the mental schema of the perceiver will 471 have to exert greater effort in persisting with consistent impression management. 472 The expected effect of impression management is a change in the perceptions of 473 professional capability of individual women who practice impression management. Practiced 474 consistently, impression management should allay the application of stereotypes to such 475 individual women, thereby modifying existing stereotypes to those that are more representative. 476 This is the effect that is expected in individuals through dyadic interactions. At the group level – 477 work group or organization, this model will hold well only if the majority of women in the group 478 project impressions that are contextually appropriate. It is my belief that the advantages Page 22 of 34 479 perceived by the individual women will create the traction necessary to change the stereotype 480 itself, without the necessity of any concerted action. 481 Outcomes subsequent to transformation of stereotypes are a change on the norms of 482 organizational behavior such as recruitment, evaluation and consequently career advancement. 483 An organization in which women are perceived more as professionals than as women 484 professionals will bring a greater degree of fairness to evaluation of female candidates during 485 recruitment. Stereotypes that are more congruous with the capabilities of professional women 486 will lead to dispassionate appraisal of their performance and outcomes consequent to such 487 processes. 488 The model is relevant to the individual woman in the organization by providing an 489 opportunity to every individual woman to alleviate the application of existing wrongful 490 stereotypes to her through the use of impression management. I also believe that given sufficient 491 number of women practicing impression management, the existing stereotypes of women will 492 undergo a transformation to a stereotype that resonates more accurately with the true image of 493 women in organizations. 494 RELUCTANCE TO USE IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT 495 Women, it has been found, are averse to the conscious use of impression management 496 tactics. This is despite knowing that their male counterparts benefit disproportionately by 497 engaging in impression management (Singh, Kumar & Vinnicombe, 2002). In another study, 498 Singh & Vinnicombe (2001) showed that women begin to engage in impression management 499 more as they progress in their careers. It is evidence of the importance of impressions in 500 organizations. But, by waiting too long to engage in it, women have to not only counter the Page 23 of 34 501 impressions of others but also overcome their own previous experiences. It is an indicator of the 502 importance of embracing the advantage of impression management early in their careers. 503 Reluctance to engage in impression management arises from the socialization, value 504 systems and ironically, its stereotypical association with men (Rudman, 1998). The nomenclature 505 of impression management tactics viz., self-promotion, supplication or intimidation also 506 contributes, probably in an indirect psychological way to the negativity image of impression 507 management. This does not deter from the fact that such behaviors are engaged in unconsciously 508 in the daily business of life: the merchant who promotes himself, the customer who tries 509 ingratiation to get a better deal, claims of entitlement made to relatives and friends and 510 attempting exemplification to influence the behavior of children. The imperative is to understand 511 that in a situation that is unfairly disadvantageous, it is a responsibility and a right to protect 512 one’s self-concept by amplifying the appropriate image against the incorrect stereotype. 513 Impression management behaviors enacted towards those from whom one does not stand 514 to gain materially may be perceived as justifiable because the outcomes are either insubstantial 515 as with bargaining or linked to emotional objectives, which make them less mercenary. 516 Organizational outcomes being directly material or linked to material outcomes make impression 517 management in the organizational context seem mercenary. However, the fact is that impressions 518 are managed in organizations on a daily basis, sub-consciously. Employees project themselves as 519 social, professional, collegial and informed. Sometimes, this is done despite not being so in 520 reality at that particular point in time, in order to project the appropriate image of the self in the 521 eyes of pertinent others. Therefore, women need to appreciate the principle on which impression 522 management is enacted and overcome their reluctance to use it appropriately to balance the 523 disadvantage created by erroneous stereotypes. Page 24 of 34 524 PITFALLS IN IMPLEMENTATION OF IMPRESSION MANAGEMENT 525 Impression management tactics usually fail in two circumstances: when they are not 526 based on authentic information and when they are used prematurely. Information that cannot be 527 confirmed by behavior leads to not only the information being discredited but also the source. 528 Premature build-up can be dangerous as it becomes contingent on actualization of the claim. 529 Therefore authenticity and credibility should be the yardstick by which any impression 530 management strategy is evaluated. 531 Keeping the objective of impression management as a tool to improve one’s image is the 532 key to being successful in creating the right impressions. The ability to control reactions in 533 situations where its effect may not be apparent sometimes also works towards making the right 534 impression. This is especially true for women as it works towards negating the stereotype of 535 ‘emotional’ women. Using impression management tactics to claim victories when used by 536 women, especially in period of time before the desired identity has been created, usually brings 537 about negative consequences. Both team members and supervisors will view such behavior as 538 typical of the ‘tyrannical’ woman whose aim is to derogate her male co-workers. It is important 539 to choose one’s battles because discretion is the better part of valor. 540 It is paramount to remember that the position at stake is not that of women as relative to 541 men but of women as an independent social category. The imperative is creating positive 542 associations with the identity group of working women. Therefore, behavior that seems to be 543 about concern for the collective ego of male co-workers is really about diminishing the 544 interference of the said male ego in their perception of female co-workers. Therefore, self- Page 25 of 34 545 confidence, self-awareness and self-control need to be exercised in order for women to create an 546 environment in which the interference of sex-stereotypes is minimal. 547 CONCLUSION 548 Sex-stereotypes affect women because they are more often than not antithetical to their 549 role as working women. It is in the interest of women to control the behavior of others, 550 particularly in response to their own conduct. This control can be achieved by influencing the 551 definition of the situation by pertinent others. Influencing such definitions means expressing 552 oneself in such a way that the impression they receive will lead them to voluntarily act in 553 consonance with one’s objectives (Goffman, 1959). Impression management is a powerful tool, 554 which if utilized with discretion and skill, can lead to ameliorating the negative consequences of 555 sex-stereotyping in organizations. Though wrongly discredited as deceitful, impression 556 management is merely a strategic representation of the self in its true state, in order to control the 557 communication and consequences of one’s actions. Impression management can be used to great 558 effect in amplifying those behaviors that otherwise get lost in communication due to the strength 559 of stereotypes in the mental framework of the target. 560 Successful impression management has consequences beyond merely alleviating the ill- 561 effects of stereotyping. Like self-fulfilling prophecies, authentic impressions, credibly conveyed 562 can result in enhancing the qualities on which such impressions are based. Therefore, a woman 563 able to successfully convey her competence finds herself exercising such competence in a variety 564 of situations, which she may not otherwise have risked. 565 Stereotypes, though often used indiscriminately, are also important tools of social 566 interaction. It is impossible to conceive of a complex society operating without the use of Page 26 of 34 567 stereotypes. Therefore, transformation of a stereotype is essentially modifying an existing 568 stereotype to resonate better with existing realities. An existing reality is that women invest a 569 great deal of resources in acquiring and demonstrating professional capabilities and as such 570 deserve commensurate rewards. Page 27 of 34 Figure 1: Modes of self-presentation Social context Social identity Organizational context Professional identity Personal identity Personal context Non-Strategic self-presentation Strategic self-presentation Page 28 of 34 Figure 2: Model of change in organizational norms through impression management Existing stereotype Transformed stereotype Impression Management Change in organizational norms Strength of stereotype Page 29 of 34 REFERENCES Benokraitis, N. V. 1997. Sex discrimination in the 21st century. In N. V. Benokraitis (Ed.), Subtle sexism: Current practice and prospects for change: 5-33. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage. Bierema, L.L. 2005. Women’s networks: a career development intervention or impediment? Human Resource Development International, 8(2): 207-24. Bolino, M. C. 1999. Citizenship and impression management: Good soldiers or good actors? Academy of Management Review, 24(1): 82-98. Bolino, M. C., Kacmar, M. K., Turnley, W. H. & Gilstrap, B. J. 2008. A multi-level review of impression management motives and behaviors. Journal of Management, 36(6): 1080-1109 Bolino, M. C., Varela, J. A., Bande, B., & Turnley, W. H. 2006. The impact of impressionmanagement tactics on supervisor ratings of organizational citizenship behavior. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 27: 281–297. Burke, R. J., Bristor, J. M. & Rothstein, M. G. 1995. The Role of Interpersonal Networks in Women's and Men's Career Development. The International Journal of Career Management, 7(3): 25-32. Cox, T. H. & Harquail, C. V. 1991. Career paths and career success in the early career stages of male and female MBAs. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 39: 54-75. Davies-Netzley, S. A. 1998. Women above the glass ceiling: perceptions on corporate mobility and strategies for success. Gender & Society, 12: 339-355 Deluga, R. J. 1991. The relationship of upward-influencing behavior with subordinateimpression management characteristics. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 21: 1145-1160. Doherty, K., & Schlenker, B.R. 1991. Self-consciousness and strategic self-presentation. Journal of Personality, 59(1): 1-18. Eagly, A.H. 2007. Female leadership advantage and disadvantage: Resolving the contradictions. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 31: 1-12. Eagly, A. H. & Johnson, B. 1990. Gender and leadership style: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 108: 233–256. Eagly, A. H., Karau, S. J. & Makhijani, M. G. 1995. Gender and the effectiveness of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 117: 125–145. Eagly, A.H., Makhijani, M.G. & Klonsky, B. G. 1992. Gender and the evaluation of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 111: 3-22. Page 30 of 34 Eagly, A. H., & Wood, W. 1991. Explaining sex differences in social behavior: A meta-analytic perspective. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17: 306–315. Elsbach, K. D., & Sutton, R.I. 1992. Acquiring organizational legitimacy through illegitimate actions: A marriage of institutional and impression management theories. Academy of Management Journal, 35: 699-738. Furst, S. A. & Reeves, M. 2008. Queens of the hill: Creative destruction and the emergence of executive leadership of women. The Leadership Quarterly, 19: 372-384 Gawronski, B. 2003. On difficult questions and evident answers: Dispositional inference from role-constrained behavior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 29, 1459–1475. Giddens, Anthony. 1984. The constitution of society: Outline of the theory of structuration. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press. Goffman, E. 1959. The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life. New York, NY: Doubleday. Greenhaus, J. H., & Parasuraman, S. 1993. Job performance attributions and career advancement prospects: An examination of gender and race effects. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 55: 273-297. Guadagno, R.E. & Cialdini, R.B. 2007. Gender differences in impression management in organizations: A qualitative review. Sex Roles, 56: 483-494 Harris, K.J., Kacmar, K.M., Zivnuska, S., & Shaw, J.D. 2007. The impact of political skill on impression management effectiveness. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92: 278–285. Hartley, E. L. & Hartley, R. E. 1952. Fundamentals of Social Psychology. New York, NY: Alfred A. Knopf. Heilman, M., Block, C., & Martell, R. 1995. Sex stereotypes: Do they influence the perceptions of managers. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 10: 237–252. Heilman, M.E., Wallen, A.S., Fuchs, D. & Tamkins, M.M. 2004. Penalties for success: Reaction to women who succeed at male gender-typed tasks. Journal of Applied Psychology, 89(3): 416427. Hopkins, M. M., O’Neil, D. A. & Bilimoria, D. 2006. Effective leadership and successful career advancement: perspectives from women in healthcare. Equal Opportunities International,25(4): 251-271 Ibarra, H. 1992. Homophily and differential returns: sex differences in network structure and access in an advertising firm. Administrative Science Quarterly, 37: 422–447. Page 31 of 34 Ibarra, H. 1993. Personal networks of women and minorities in management: a conceptual framework. Academy of Management Review, 18: 56–87. Jerdee, T. H. & Rosen, B. 1976. Factors Influencing the Career commitment of women. Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Psychological Association. Jones, E. E. & Pittman, T. S. 1982. Toward a general theory of strategic self-presentation. In J. Suls (Ed.), Psychological perspectives on the self, Vol. 1: 231-262. Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Kacmar, K. M., & Carlson, D. S. 1999. Effectiveness of impression management tactics across human resource situations. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29: 1293–1315. Kidder, D. L. & Parks, J. M. 2001. The good soldier: Who is s(he)? Journal of Organizational Behavior, 22: 939-959. Leary, M. R. & Kowalski, R. M. 1990. Impression management: A literature review and twocomponent model. Psychological Bulletin, 107: 34-47. Lewis, M. A., & Neighbors, C. 2005. Self-determination and the use of self-presentation strategies. Journal of Social Psychology, 145: 469-489. Lyness, K.S. & Heilman, M.E. 2006. When fit is fundamental: Performance evaluations and promotions of upper-level female and male managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 91: 777785. Lyness, K. S., & Thompson, D. E. 1997. Above the glass ceiling? A comparison of matched samples of female and male executives. Journal of Applied Psychology, 82: 359-375. McCracken, D. M. 2000. Winning the talent war for women: Sometimes it takes a revolution. Harvard Business Review, 78(6): 159. Moore, G. 1990. Structural determinants of men's and women's personal networks. American Sociological Review, 55: 726-35. Nieva, V. F. & Gutek, B. A. 1980. Sex effects on evaluation. Academy of Management Review, 5(2): 267–276. O’Neil, D. A., Hokins, M. M. & Bilimoria, D. 2008. Women’s careers at the start of the 21st century: Patterns and paradoxes. Journal of Business Ethics, 80: 727-743. Oakley, J.G. 2000. Gender-based barriers to senior management positions: understanding the scarcity of female CEOs. Journal of Business Ethics, 27: 321-334. Ragins, B.R. & Sundstrom, E. 1989. Gender and power in organizations: A longitudinal perspective. Psychological Bulletin, 105: 51-88. Page 32 of 34 Roberts, L. M. 2005. Changing faces: professional image construction in diverse organizational settings. Academy of Management Review, 30(4): 685-711. Rose, G. L. & Andiappan, P. Sex effects of managerial hiring decisions. Academy of Management Journal, 21: 104–112. Rosenfeld, P. R., Giacalone, R. A., & Riordan, C. A. 1995. Impression management in organizations: Theory, measurement, and practice. New York, NY: Routledge. Rudman, L. A. 1998. Self-promotion as a risk factor for women: The costs and benefits of counter-stereotypical impression management. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74: 629-645. Ryan, M. K. and S. A. Haslam (2007). ‘The glass cliff: exploring the dynamics surrounding the appointment of women to precarious leadership positions’, Academy of Management Review, 32: 549–572. Schein, V. E. 1973. The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57: 95-100. Schein, V.E. 1996. Think manager-think male: a global phenomenon. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 17: 33-41. Schein, V.E. 2007. Women in management: reflections and projections. Women in Management Review, 22(1): 6-18. Schlenker, B. R. 1980. Impression management: The self-concept, social identity, and interpersonal relations. Monterey, CA: Brooks/Cole. Siadnius, J. and Veniegas R. C. 2000. Gender and race discrimination: The interactive nature of disadvantage. In S. Oskamp (Ed.), Reducing prejudice and discrimination: 47-69. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates. Singh, V. & Vinnicombe, S. 2001. Impression management, commitment and gender: Managing others' good opinions. European Management Journal, 19(2): 183-194 Singh, V., Kumra, S. & Vinnicombe, S. 2002. Gender and impression management: Playing the promotion game. Journal of Business Ethics, 37: 77-89. Small, D. A., Gelfand, M., Babcock, L. & Gettman, H. 2007. Who goes to the bargaining table? The influence of gender and framing on the initiation of negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 93: 600–613. Page 33 of 34 Stangor, C., & Schaller, M. 2000. Stereotypes as individual and collective representations. In C. Stangor (Ed.), Stereotypes and prejudice: Key readings in social psychology: 63-82. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. Stevens, C. K., & Kristof, A. L. 1995. Making the right impression: A field study of applicant impression management during job interviews. Journal of Applied Psychology, 80: 587–606. Tajfel, H., & Forgas, J. 2000. Social categorization: Cognitions, values and groups. In C. Stangor (Ed.), Stereotypes and prejudice: Key readings in social psychology: 49-63. Philadelphia, PA: Psychology Press. Tedeschi, J. T. (Ed.). 1981. Impression management theory and social psychological research. New York: Academic Press. Tedeschi, J. T., Bonoma, T. V. & Schlenker, B. R. 1972. Influence, decision and compliance. In J. T. Tedeschi (Ed.), The social influence processes: 346-418. Chicago, IL: Aldine Atherton Tedeschi, J.T. & Melburg, V. 1984. Impression management and influence in the organization. In S. B. Bachrach & E. J. Lawler (Eds.), Research in the sociology of organizations, Vol. 3: 3158. Greenwich, CT: JAI Press. Van Emmerik, I.J.H. 2006. Gender differences in the creation of different types of social capital: a multilevel study. Social Networks, 28(1): 24-37. Walters, A.E., Stuhlmacher, A.F. & Meyer, L.L. 1998. Gender and negotiator competitiveness: A meta-analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 76, 1–29. Wayne S. J. & Liden R. C. 1995. Effects of impression management on performance ratings: A longitudinal study. Academy of Management Journal, 38: 232–260. Page 34 of 34