Hotel Investments Handbook - Chapters 2-7

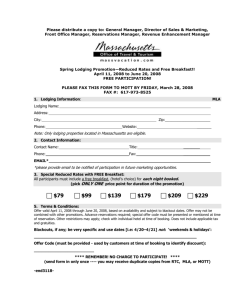

advertisement