ENTRY STRATEGIES FOR INTERNATIONAL CONSTRUCTION

advertisement

The Pennsylvania State University

The Graduate School

Department of Architectural Engineering

ENTRY STRATEGIES FOR INTERNATIONAL CONSTRUCTION MARKETS

A Thesis in

Architectural Engineering

by

Chuan Chen

© 2005 Chuan Chen

Submitted in Partial Fulfillment

of the Requirements

for the Degree of

Doctor of Philosophy

December 2005

The thesis of Chuan Chen was reviewed and approved* by the following:

John I. Messner

Assistant Professor of Architectural Engineering

Thesis Advisor

Chair of Committee

Ann E. Echols

Assistant Professor of Management and Organization

Michael J. Horman

Assistant Professor of Architectural Engineering

David R. Riley

Associate Professor of Architectural Engineering

H. Randolph Thomas

Professor of Civil Engineering

Richard A. Behr

Professor of Architectural Engineering

Head of the Department of Architectural Engineering

*Signatures are on file in the Graduate School

iii

ABSTRACT

An entry mode is an institutional arrangement that makes possible the entry of a

company’s services, technology, human skills, management or other resources into a

foreign country. Selecting an inappropriate entry mode can lead to significant negative

consequences. Entry mode selection is therefore one of the most critical decisions in

international construction. The purpose of this research was to understand various entry

modes and improve the selection decision for international construction companies.

Comparative case studies identified and defined 10 basic entry modes utilized in

the international construction arena: 1) strategic alliance, 2) local agent, 3) licensing, 4)

joint venture company, 5) sole venture company, 6) branch office / company, 7)

representative office, 8) joint venture project, 9) sole venture project, and 10) BOT /

equity project. Basic entry modes can be combined or sequenced throughout the entry

into a single geographic market. These entry modes can be classified into a dichotomy:

permanent entry (joint venture company, sole venture company, branch office / company,

and representative office) versus mobile entry (joint venture project, sole venture project,

and BOT / equity project), which differ primarily in investment risk exposure, resource

commitment, and flexibility.

Complementary business and economic theories suggested 13 home country

specific, home-host country specific, host country specific, and entrant specific factors

that can influence the selection between permanent entry and mobile entry. Hypotheses

were developed centering on these factors, e.g., with other conditions being equal,

contractors are less likely to use permanent entry modes for a target market with a high

competitive intensity. Binary logistic regression analysis of empirical data was used to

test these hypotheses. The results were interpreted and analyzed. In addition, the

regression analysis, together with a two sample t-test, provided a descriptive as well as

normative statistical model for selecting superior entry modes to penetrate target foreign

construction markets.

iv

TABLE OF CONTENTS

LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................... x

LIST OF TABLES .....................................................................................................xiii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ...................................................................................... xv

CHAPTER 1

1.1

1.2

1.3

1.4

1.5

1.6

1.7

INTRODUCTION ...........................................................................1

Background.................................................................................................... 1

Problem Statement......................................................................................... 2

Research Objectives....................................................................................... 4

Research Methodology .................................................................................. 5

Scope..............................................................................................................5

Relevance.......................................................................................................8

Reader’s Guide .............................................................................................. 8

CHAPTER 2

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY................................................... 10

2.1 Introduction....................................................................................................10

2.2 Research Process ........................................................................................... 12

2.2.1 Define Research Questions.................................................................. 13

2.2.2 Entry Mode Definition ........................................................................ 15

2.2.3 Entry Mode Selection .......................................................................... 15

2.3 Research Techniques .....................................................................................16

2.3.1 Data Collection....................................................................................16

2.3.2 Case Study ........................................................................................... 17

2.3.3 Survey................................................................................................ 19

2.3.4 Statistic Analysis .................................................................................20

2.4 Summary........................................................................................................ 20

CHAPTER 3

LITERATURE REVIEW...............................................................23

3.1 Entry as a Strategic Issue...............................................................................24

3.1.1 Strategic Planning and Management: a Construction Perspective ......24

3.1.2 Internationalization Process................................................................. 31

3.1.3 Entry Barriers ......................................................................................33

3.1.4 Entry Timing ....................................................................................... 34

3.1.5 Market Selection..................................................................................35

3.1.6 Entry Mode Selection .......................................................................... 38

3.2 Entry as an Organizational Issue ...................................................................41

v

3.3 Entry for International Construction Markets................................................42

3.3.1 International Project Go / No-Go Decision .........................................42

3.3.2 Internationalization of Construction Firms .........................................46

3.3.3 Some Entry Modes Examined in International Construction

Literature.............................................................................................. 47

3.3.4 International Construction Market Structure, Trends, and Future ......51

3.3.5 Other Related Topics in International Construction............................52

3.4 Concluding Remarks ..................................................................................... 54

3.5 Summary........................................................................................................ 55

CHAPTER 4 AN OVERVIEW OF THE INTERNATIONAL

CONSTRUCTION MARKET ENTRY............................................................ 57

4.1 A General Review of the Hisotry of International Construction...................57

4.1.1 Pre-World War II period .....................................................................57

4.1.2 Post-World War II Period until 1992...................................................59

4.1.3 The Past Decade: an Empirical Analysis.............................................63

4.1.3.1 Major Forces in the Global Construction Market ..................... 64

4.1.3.2 Major Construction Markets .....................................................65

4.1.3.3 Firm Market Share by Regions .................................................69

4.2 Comments on the Chronological Review ...................................................... 70

4.3 The Increasing Popularity of Permanent Entry .............................................71

4.4 Voices from the Industry during the Past Two Decades: A New Trend ....... 72

4.5 An Empirical Investigation of the Mobile Versus Permanent Entry

Dichotomy ..................................................................................................... 77

4.6 Summary........................................................................................................ 83

CHAPTER 5

ENTRY MODE DEFINITION ...................................................... 84

5.1 Methodology.................................................................................................. 84

5.2 Basic Entry Modes for International Construction Markets..........................88

5.2.1 Strategic Alliance (SA)........................................................................ 88

5.2.2 BOT / Equity Project ...........................................................................91

5.2.3 Joint Venture (JV) Project .................................................................94

5.2.4 Representative Office (RO)................................................................. 96

5.2.5 Licensing ............................................................................................. 98

5.2.6 Local Agent (LA) ................................................................................ 99

5.2.7 Joint Venture (JV) Company......................................................... 100

5.2.8 Sole Venture (SV) Company...............................................................103

5.2.9 Branch Office / Company (BO) ..........................................................104

5.3 Evaluation of the Entry Modes ......................................................................106

vi

5.4 Transferability and Compatibility of Entry Modes .......................................109

5.5 Entry Mode-Country Relationship (Applicability)........................................110

5.6 Summary........................................................................................................ 112

CHAPTER 6 RELATIONSHIPS BETWEEN MARKET ENTRY MODES ... 113

6.1 Classifying Entry Modes by Setting Characteristics .....................................113

6.2 A Synthesis of Setting Characteristics of Entry Modes.................................119

6.3 Different Effects of Entry Modes ..................................................................121

6.3.1 Risk Exposure...................................................................................... 122

6.3.2 Control................................................................................................. 123

6.3.3 Resource Commitment ........................................................................ 124

6.3.4 Flexibility ............................................................................................125

6.4 A Synthesis of Different Effects.................................................................... 125

6.5 An Investigation of Different Effects of Entry Modes .................................. 127

6.6 Entry Mode Combination and Sequencing.................................................... 129

6.7 A Review of the Mobile versus Permanent Entry Dichotomy ......................133

6.8 Summary........................................................................................................ 134

CHAPTER 7 THEORY DEVELOPMENT ......................................................... 136

7.1 Review of Related Theories...........................................................................136

7.1.1 Transaction Cost Economics ............................................................... 136

7.1.2 Stage Models of Entry .........................................................................138

7.1.3 Ownership Location Internalization (OLI) Paradigm .........................139

7.1.4 Organizational Capability....................................................................140

7.1.5 Bargaining Power ................................................................................ 141

7.1.6 Institutional / Cultural Theory .............................................................142

7.2 A Synthesis of Different Theories from Process Perspective........................143

7.3 Hypotheses Development ..............................................................................148

7.3.1 Home Country Factors ........................................................................ 149

7.3.1.1 Home Market Attractiveness.....................................................150

7.3.1.2 Long Term Orientation..............................................................151

7.3.1.3 Uncertainty Avoidance.............................................................. 152

7.3.2 Home Country-Host Country Factors ................................................. 153

7.3.2.1 Trade Link .................................................................................153

7.3.2.2 Cultural Distance....................................................................... 154

7.3.2.3 Colonial Link.............................................................................155

7.3.2.4 Language proximity ..................................................................156

7.3.3 Host Country Factors........................................................................... 157

7.3.3.1 Host Market Attractiveness ....................................................... 157

vii

7.3.3.2 Investment Risk.........................................................................158

7.3.3.3 Entry Restriction .......................................................................159

7.3.3.4 Competitive Intensity ................................................................160

7.3.4 Firm Factors.........................................................................................161

7.3.4.1 Firm Size ...................................................................................161

7.3.4.2 Multinational Experience ..........................................................162

7.4 Interaction Effects..........................................................................................163

7.5 A Synthesis of Influencing Factors................................................................164

7.6 Summary........................................................................................................ 165

CHAPTER 8 THEORY TESTING....................................................................... 166

8.1 Methodology.................................................................................................. 166

8.1.1 Sample ................................................................................................. 166

8.1.2 Analytical Approach............................................................................ 168

8.2 Measurement of Variables.............................................................................169

8.2.1 Measurement of the Dependent Variable ............................................169

8.2.2 Measurement of Independent Variables .............................................. 171

8.2.2.1 Home Country Market Attractiveness and Host Country

Market Attractiveness .....................................................................171

8.2.2.2 Long-term Orientation, Uncertainty Avoidance, and

Cultural Distance.............................................................................172

8.2.2.3 Trade Link .................................................................................173

8.2.2.4 Colonial Link and Language Proximity ....................................173

8.2.2.5 Investment Risk.........................................................................174

8.2.2.6 Entry Restriction .......................................................................174

8.2.2.7 Competitive Intensity ................................................................176

8.2.2.8 Firm Size ...................................................................................177

8.2.2.9 Multinational Experience ..........................................................177

8.2.2.10 Fit ............................................................................................ 178

8.2.3 Control Variable – Home Country Economic Level ...........................178

8.3 Results............................................................................................................ 178

8.3.1 Logistic Regression ............................................................................. 179

8.3.1.1 Main Effects ..............................................................................182

8.3.1.2 Interaction Effects .....................................................................187

8.3.2 T Test...................................................................................................190

8.4 Conclusions and Managerial / Future Research Implications .......................192

8.5 Summary........................................................................................................ 194

CHAPTER 9

CONCLUSIONS..............................................................................195

viii

9.1 Summary of the Research..............................................................................195

9.1.1 Characterization of the Global Construction Market Trend from a

Market Entry Perspective .......................................................................196

9.1.2 Development of a Taxonomy of Entry Modes for the Global

Construction Market...............................................................................196

9.1.3 Differentiation of Entry Modes ........................................................... 197

9.1.4 Identification of Factors Influencing Entry Mode Selection ...............198

9.1.5 Hypothesis Testing and Model Development for Entry Mode

Selection ................................................................................................. 199

9.2 Contributions of the Research .......................................................................200

9.2.1 A Taxonomy of Entry Modes for International Construction

Markets...................................................................................................200

9.2.2 Influencing Factors for Entry Mode Selection in International

Construction ...........................................................................................201

9.2.3 A Descriptive and Normative Model for Entry Mode Selection in

International Construction...................................................................... 201

9.2.4 Innovation in Research Methodology for Construction

Management ........................................................................................... 202

9.3 Limitations of the Research ...........................................................................202

9.3.1 Selection between Two Groups of Entry Modes................................. 202

9.3.2 Limited Factors Included in the Model ...............................................203

9.3.3 Data Accessibility................................................................................203

9.4 Future Research .............................................................................................204

9.4.1 Market Selection..................................................................................204

9.4.2 Selection between Basic Entry Modes ................................................204

9.4.3 Principles for Combining Different Entry Modes ...............................205

9.4.4 The Culture of International Contractors ............................................205

9.4.5 The Application of Organizational Capability in Entry Mode

Selection ................................................................................................. 205

9.5 Summary........................................................................................................ 206

Bibliography ............................................................................................................... 207

Appendix A

Cultural Index Scores for Countries (Hofstede 2001)....................222

Appendix B

Investment Risk Ratings ...................................................................224

Appendix C Lingual, Colonial, and Distance Relationships between

Countries ............................................................................................................. 227

Appendix D

Trade Link between Countries (Partial) ......................................... 229

ix

Appendix E Number of Top International Contractors in Each Market

(1992-2001) .......................................................................................................... 231

Appendix F

Entry Restriction ...............................................................................233

Appendix G

Construction Spending (1996 – 2000).............................................. 235

Appendix H

Revenue of International Contractors (Partial) .............................237

Appendix I

Entry Times of International Contractors (1992 – 2001,

Partial) ................................................................................................................. 239

Appendix J

World Bank Country Groups by Income ........................................241

Appendix K

Permanent Entries of International Contractors (Partial) ...........244

Appendix L

ENR Country Group by Region....................................................... 246

Appendix M Market Entries of Selected International Contractors (Part of

the Matrix for the Year 2001)............................................................................ 249

Appendix N

ENR Top 225 International Construction Firms (Year 2001) ......251

Appendix O

Survey Questionnaire ....................................................................... 257

Appendix P How The Top International Contractors Shared the Global

Market (Partial) .................................................................................................. 263

Appendix Q

Contractors Investigated for Entry Mode Selection ...................... 265

Appendix R

Legal and Technical Constraints against Market Entry ...............269

Appendix S

Cultural Distances between Selected Markets ................................ 285

Appendix T

Selected Case Studies ........................................................................ 290

T.1

T.2

T.3

T.4

T.5

T.6

T.7

T.8

T.9

Strategic Alliance .......................................................................................... 291

BOT Project...................................................................................................295

Joint Venture Project..................................................................................... 296

Representative Office....................................................................................297

Licensing .......................................................................................................298

Local Agent ...................................................................................................299

Joint Venture Company................................................................................. 307

Sole Venture Company ................................................................................. 309

Branch Office ................................................................................................310

x

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1.1: The Elements of an International Market Entry Strategy (Source:

Root 1987) ............................................................................................................ 6

Figure 2.1: Various Research Paradoxes and Typologies Used in Construction

..............................................................................................................................10

Figure 2.2: Research Process .................................................................................. 13

Figure 2.3: The Structure of the Main Knowledge Body of Statistics....................22

Figure 3.1: The Framework for Contextual Issues for International Market

Entry ..................................................................................................................... 24

Figure 3.2: A holistic Strategic Planning Methodology for Construction Firms

(Source: Alarcon and Ashley 1992) .....................................................................29

Figure 3.3:

Different Schools of Strategies

(Source: Cheah 2002) ......................31

Figure 3.4: Phases in Global Marketing Evolution (Source: Douglas and Craig

1995) .....................................................................................................................32

Figure 3.5: The Basic Mechanism of Internationalization – State And Change

Aspects (Source: Johanson 1977).........................................................................33

Figure 3.6: Decision Framework for Global Market Entry (Source: Levy and

Yoon 1995) ...........................................................................................................37

Figure 3.7: A Hierarchical Model of Choice of Entry Modes (Source: Pan and

Tse 2000) .............................................................................................................. 38

Figure 3.8: Evolution of A Manufacturer’s Decision on Entry Mode (Source:

Root 1987) ............................................................................................................39

Figure 3.9: A Schematic Representation of Entry Choice Factors (Source:

Agarwal and Ramaswami 1992)...........................................................................40

Figure 3.10: Interaction between Corporate Strategy and Organization ..................41

Figure 3.11: Entry Decision Process for International Projects (Source: Han 1999)

..............................................................................................................................44

Figure 3.12: Project Evaluation Process Model (Source: Messner 1994) ................ 45

xi

Figure 4.1: Distribution Of International Contractors’ Revenue (2001) ................65

Figure 4.2: International Construction Market Segmentation 1992-2001 ..............66

Figure 4.3: Volume of International Revenue by Geographic Region ................... 67

Figure 4.4: Internal Market Attractiveness Based on Volume of Internal Trade

Instances ............................................................................................................... 68

Figure 4.5: External Market Attractiveness Based on Volume of Internal Trade

Instances ............................................................................................................... 69

Figure 4.6: Volume of Top 225 Contractor Markets in the Global Market............ 70

Figure 4.7: The Value Chain of Construction Projects (Source: Miles 1995)........ 76

Figure 4.8:

Comparison Between Mobile Entry And Permanent Entry .................76

Figure 4.9: Chronology of Permanent Entry...........................................................79

Figure 4.10: Chronology of Mobile Entry (1980-2001) ........................................... 80

Figure 4.11: Distribution of Time Lag between Permanent Residence

Establishment and First Business Implementation ...............................................81

Figure 4.12: Distribution of Testing Time from Fist Project and Establishment of

Permanent Residence............................................................................................82

Figure 5.1: Content Analysis Tool for Each Case Study ........................................87

Figure 5.2: Relationship Mapping for Strategic Alliance .......................................91

Figure 5.3: Relationship Mapping for BOT / Equity Project..................................93

Figure 5.4: Relationship Mapping for Joint Venture Project..................................96

Figure 5.5: Relationship Mapping for Representative Office.................................98

Figure 5.6: Relationship Mapping for Joint Venture Company..............................102

Figure 5.7: Relationship Mapping for Sole Venture Company ..............................104

Figure 5.8: Relationship Mapping for Branch Office / Company ..........................106

Figure 5.9:

Transferability and Compatibility of Each Entry Mode........................109

xii

Figure 6.1:

Grouping Entry Modes Regarding Cooperative v. Competitive........... 115

Figure 6.2: Grouping Entry Modes Regarding Hierarchical Level ........................115

Figure 6.3: Grouping Entry Modes Regarding Contractual v. Investment.............116

Figure 6.4: Grouping Entry Modes Regarding Ownership.....................................116

Figure 6.5: Grouping Entry Modes Regarding Supportive v. Principle .................117

Figure 6.6: Grouping Entry Modes Regarding Market v. Hierarchy......................118

Figure 6.7: Grouping Entry Modes Regarding Mobile v. Permanent.....................118

Figure 6.8: Grouping Entry Modes Regarding Mobile v. Permanent (Used for

Mode Selection)....................................................................................................119

Figure 6.9: Grouping Entry Modes with Multiple Dimensions .............................. 121

Figure 6.10: Relationships between Effects..............................................................126

Figure 6.11: Evolution of Entry Modes in International Construction ..................... 131

Figure 6.12: Relationship between Permanent Entry and Mobile Entry ..................134

Figure 7.1: A Synthesis of Different Theories from a Process Perspective............146

Figure 7.2: Contingency Relationships between Factors and Entry Mode

Selection ............................................................................................................... 149

Figure 8.1: Relationships between Independent and Dependent Factors ...............169

Figure 8.2: Interaction Effects: Entry Restriction by Home Market Growth .........188

Figure 8.3: Interaction Effects: Entry Restriction by Cultural Distance.................189

Figure 8.4: Interaction Effects: Entry Restriction by Investment Risk...................190

Figure T.1: The Contractual Arrangement of the Shanghai Dachang Water

Plant Project..........................................................................................................295

xiii

LIST OF TABLES

Table 3.1: Triggers to Each Stage of Internationalization (Source: Douglas and

Craig 1995) ........................................................................................................... 32

Table 3.2: Responses in Organization Structure at Different Stages in the

Evolution of a Global Enterprise (Source: Root 1987) ........................................ 42

Table 4.1: Regional And Time Distribution of Leading International Contractors

(1992-2001) .......................................................................................................... 64

Table 4.2: Contractors Investigated for Mobile Entry Versus Permanent Entry........ 78

Table 5.1: Database..................................................................................................... 86

Table 5.2: Respondent Particulars .............................................................................. 107

Table 5.3: Entry Mode Evaluation.............................................................................. 107

Table 5.4: Applicability of Entry Modes for Selected Markets..................................111

Table 6.1: The Taxonomy of Entry Modes for International Construction Markets..114

Table 6.2: A Synthesis of Setting Characteristics of Entry Modes.............................120

Table 6.3: Difference Between Entry Modes Regarding Control and Contractual

Risk Exposure....................................................................................................... 128

Table 6.4: Difference between Entry Modes Regarding Resource Commitment,

Investment Risk Exposure, and Flexibility........................................................... 128

Table 6.5: Dataset for Investigating Combination and Sequencing of Entry

Modes ................................................................................................................... 130

Table 6.6: Combination of Entry Modes ....................................................................132

Table 7.1: Difference between Transaction Cost Economics and Organizational

Capability (Source: Madhok 1997) ...................................................................... 140

Table 7.2: Differences and Complements between Different Theories......................147

Table 7.3: Cultural Dimension Scores (0 = Low, 100 = High) .................................. 151

Table 7.4: The Hypotheses (Main Effects) ................................................................. 164

xiv

Table 8.1: Contractors’ Original Regions................................................................... 167

Table 8.2: Regional Distribution of Sampled Markets ...............................................168

Table 8.3: Scale to Measure Legal Barriers................................................................175

Table 8.4: Correlation Matrix .....................................................................................180

Table 8.5: Determinants of Entry Mode Selection: Binary Logistic Test (n=1998:

Mobile entry = 867; Permanent entry = 1131) ..................................................... 181

Table 8.6: Testing Results........................................................................................... 183

Table 9.1: Definitions of Entry Modes for International Construction Markets ........ 197

Table 9.2: Results of Hypothesis Testing ................................................................... 200

xv

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank my thesis committee for their encouragement, advice, and

feedback throughout this research. I am extremely grateful to my advisor, Dr. John

Messner, for his motivation, direction, support, patience, and friendship. I have learned

much from him not just about methods and skills in academic research, but also about the

United States and attitudes about career and family. His mentorship will continue to

stimulate me to resolve challenges ahead. I am indebted to Dr. Ann Echols, for her

stimulation, advice, patience, and inputs. She showed me a discipline that is worthy of

long term exploration of its application to the construction industry. I would like to thank

Dr. Randolph Thomas, for his selflessness in imparting to me his research experience and

philosophy which I will benefit from throughout my academic career. I would like to

thank Dr. David Riley and Dr. Michel Horman for their varying perspectives on this

research as well their encouragement, support, and friendship.

I would like to thank all of my previous teachers, professors, friends, and

classmates for their encouragement and guidance. It is their joint efforts that enable me to

pursue this terminal degree. I am especially thankful to a teacher at my elementary school

who first encouraged me to pursue a doctorate more than ten years ago.

I am grateful to my parents for their unconditional support in every way

throughout these years. Even in the small town in China cut off from the rest of the

world, they planted some beautiful dreams in my heart and encouraged me to pursue

them. I thank my sister Ying Chen and my brother-in-law Zuohua Yue for their love and

encouragement. I am especially thankful to my wife, Zirui Qiu, for her love, support,

patience, and cooking skills over the years since we got married. She made the long and

difficult doctorate pursuit process vital and happy. She is my wonderful companion with

whom to challenge the future. Thank you, Zirui!

xvi

I am leaving Happy Valley, my fifth hometown back for China, but I will remain

in the academic circle. I look forward to the chance to apply what I have learned here to

contribute to the construction discipline and industry of my motherland.

Thank you!

Chuan Chen (“Victor”)

1

CHAPTER 1

INTRODUCTION

1.1 Background

The international construction sector is an important part of the global economy.

Mawhinney (2001) defined international construction as construction projects where one

company, resident in one country, performs construction works in another country. This

simple definition, consistent with other definitions (Gibson et al. 2003; U.S. Department

of Commerce 1984), underpins the scope of activities investigated in this research.

Through international projects, contractors can achieve opportunities for growth

that may be unavailable in their domestic market, and capitalize on expertise and

experience gained from long involvement in a type of construction or some sophisticated

technology (Ashley and Boner 1987). To the contractors’ country of origin (home

country), the benefits from international construction can be grouped into six categories:

1) expatriation of profits from foreign projects; 2) exports of equipment and materials as

a direct result of foreign project work; 3) exports of services (such as insurance,

transportation, and financing) as a direct result of foreign project work; 4) repatriation of

personal income in the foreign projects; 5) follow-up procurement of home country goods

and services resulting from the continued operation and maintenance of foreign projects;

and 6) employment of home country nationals both in home and host countries (U.S.

Department of Commerce 1984). The host country can have projects completed when it

does not have the required expertise or resources, obtain technology transfer, benefit from

increased competition in domestic markets for quality and efficiency improvement, and

sometimes, obtain partial or entire financing for the project.

2

Han and Diekmann (2001) summarized four globalization factors in the last

decade that may expand opportunities for contractors in international construction

markets: 1) all signatory countries to the GATT [now, WTO] system opening their

domestic markets; 2) the development of regional Free Trade Blocs; 3) establishment of

world standards; and 4) rapid developments in telecommunication, travel and other

related industries.

However, it is not easy to make the best of the opportunities in international

construction markets. Working in an international setting often requires a much wider

view of the project’s context than with domestic projects where project expertise is often

disconnected from other aspects of the business; and international projects manifest more

types of risks than domestic projects (CII 2003; Han and Diekmann 2001; Mawhinney

2001). To survive and grow in the international construction arena, a contractor cannot

afford poor decisions in assigning their limited resources to diminishing markets, while

avoiding the attractive ones. In crafting effective entry strategies, contractors must, first

and foremost, evaluate market attractiveness and accessibility systematically and

objectively, however in the construction management knowledge body there is no

systematic tool or method available for this purpose. The decision to enter a new foreign

market is of critical importance for the company’s profit making ability and sustainable

growth. To domestic market oriented contractors, it is also important to understand the

foreign competitors’ entry decision to protect their competitive position in the domestic

construction market for growth and survival in a world of global competition.

1.2 Problem Statement

The construction sector is project-based (Messner 1994). This fundamental

feature determines that the entry decision is substantially centering on ‘Go / No-Go’ or

‘Bid / No-Bid’ decisions for a specific project in the targeted new market (Han and

Diekmann 2001). Ashley and Boner (1987) observed that:

3

“Multinational contractor operations abroad are project specific; offices

and key personnel are mobilized and set up prior to construction and are

usually closed and withdrawn following project conclusion. When

involved in multiple projects in one country over a prolonged period of

time, the project office may acquire a greater degree of permanence and at

some point can become recognized as a branch office of the firm. It rarely,

however, develops the kind of permanence exhibited by a wholly owned

subsidiary of a typical multinational enterprise.”

Entries in the international construction sector are more often triggered on a

contingent basis than in other international trade sectors like manufacturing. Long term

presence and increasing commitment are frequently dependent on market performance

rather than strategic vision and goals. However, new changes in the 1990s started to drive

a tendency of market entries aiming at a more sustainable and permanent presence in new

markets, including:

1) The continuous prosperousness of some construction markets in developed

economies, like that of the United States. Sustainable presence in these

markets can be profitable.

2) The continuous increase in demand within some construction markets in

developing economies, e.g., China and the Czech Republic. Early entry and

establishment of permanent residence to exploit the growth are strategically

important.

3) The dwindling size of some construction markets in export-oriented

economies, like Europe and Japan. Contractors have little choice but to turn

to foreign markets for survival and growth.

4) The emergence of innovative investment type entry modes, like mergers and

acquisitions.

5) Increasing size of global construction players. Frequent cross border mergers

or acquisitions make very large international construction firms, who place

more emphasis on entry issues on a corporate level.

4

Market entry has increasingly become a strategic and corporate-level decision. These

market entry strategies guide lower level ‘Go / No-Go’ or ‘Bid / No-Bid’ decisions

centering on specific projects within a market.

As more and more construction firms enter foreign markets, several questions of

interest to both academicians and practitioners will be increasingly asked including:

“How do construction firms enter individual foreign markets?” and “How does this entry

behavior vary across different types of firms and different entry situations in the

construction sector?”. The answers to these and other related questions in the area of

international construction are not clear. The existing knowledge of entry modes in firms

has been accumulated mostly in the context of the manufacturing industry. Given that

construction has distinct characteristics which make a wholesale transfer of concepts and

theories serving the manufacturing industry unrealistic, there is a need for adapting this

knowledge, and for developing new concepts and frameworks to meet the unique nature

of the construction industry.

1.3 Research Objectives

The goal of this research is to develop a systematic taxonomy of entry modes

specific to international construction markets along with a model for entry mode

selection. To realize this goal, the following objectives need to be accomplished:

1) To understand the history, status quo, and trends in the global construction

market from an entry perspective;

2) To define a taxonomy of market entry modes that construction companies use

to enter selected international markets prior to attaining business

sustainability within the markets; and

3) To develop a market-entry mode selection model for construction companies

to achieve optimal entry performance.

5

1.4 Research Methodology

This research applies theories and techniques previously developed and supported

in general international business fields; analyzes data from multiple sources; and elicits

opinions from seasoned leaders in the international construction industry, through the

following research steps:

1) Review literature in strategic management, international business, and

international construction to identify knowledge gaps and relevant theory;

2) Review the history and current trends in the global construction market to

identify the importance of entry related strategic decisions;

3) Define entry modes for international construction markets through

comparative case studies;

4) Differentiate and group entry modes according to their differences and

similarities in setting and effects, and identify permanent entry versus mobile

entry as the dichotomical selection problem for further research;

5) Develop hypotheses about entry mode selection through theoretical reasoning

and capitalizing on findings from previous research in international business;

and

6) Collect data and use binary logistic regression analysis to test hypotheses as

well as develop a model for selection between permanent entry and mobile

entry modes.

A more detailed description of this research process is provided in Chapter 2.

1.5 Scope

An international market entry strategy is a comprehensive plan which sets forth

the objectives, goals, resources, and policies that will guide a company’s international

business operations over a future period long enough to achieve sustainable growth in

world markets (Root 1987). Market entry strategies require decisions on (Root 1987): 1)

the choice of a target market; 2) the objectives and goals in the target market; 3) the

6

choice of an entry mode to penetrate the target country; 4) the marketing plan to penetrate

the target market; and 5) the control system to monitor performance in the target market

(see Figure 1.1). In some literature (Brouthers 1995; Buckley and Casson 1998; Taylor et

al. 2000; Tse et al. 1997), entry strategy and entry mode are interchangeably used.

In

general business literature, the mainstream research on market entry strategies focuses on

two issues: 1) market selection and 2) entry mode selection. This may be because these

two questions are most important and difficult. The scope of this research specifically

focuses on entry mode selection.

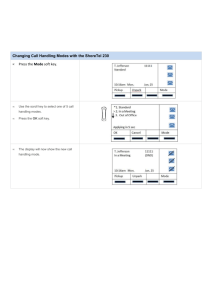

Figure 1.1: The Elements of an International Market Entry Strategy (Source: Root 1987)

Market can be defined by different dimensions, such as geographic location, size,

client, product, and service. From an entry strategy perspective, market entry decision

issues normally center on cross-border activities. For example, in Root’s theory market is

focused on country (Root 1987). This research focuses on geographic markets and

therefore, if not specifically indicated otherwise, “market” is identical to “country”.

According to Drewer (2001), the international construction system is made up of

four segments: 1) design consultancy, 2) construction, 3) labor trade, and 4) material

production. Among the four, design service is the most mobile in crossing country

borders and leaping entry and exit barriers. The labor market depends upon construction

markets to a great extent, and is normally traveling in a single direction from developing

7

countries to developed economies. Cross-border material transactions are also dependant

on construction and quite similar to common goods trade. International construction

activities attract more extensive attention from different economies, and they also face

more challenges. The scope of this research emphasizes the construction segment.

However, since many contractors also provide design services, especially in industrial

and petroleum projects or projects delivered under a design-build or turnkey delivery

system, design consultancies are also addressed in this research when they are combined

with the construction services for a project.

The foundation of the construction industry has been the focus of the debate to

whether it is production (Newcombe 1976) or service delivery (Fleming 1988;

Hillebrandt 1984). This question is important since the perspective from which one looks

at the industry defines its markets, and consequently the strategic processes which are

used to govern and direct the construction organization (Langford and Male 2001). The

latest mainstream viewpoint is that construction is a hybrid industry of both product and

service components (Langford and Male 2001; Maloney 2002; Warf 1991).

“…In the construction industry over the last twenty years, …there is a

strong differentiation between contractors who provide management

services and contractors who undertake to build the physical product.

…Large firms providing management contracting and project

management services may be regarded as part of the service industry,

whereas those providing resources which are used to construct the

building might be better described as manufacturing–style organizations.”

(Langford and Male 2001)

This research emphasizes the higher level of service featured activities that large

international contractors frequently undertake.

Except for the above mentioned restrictions, the entry mode taxonomy and entry

mode selection model developed in this research are generic tools that can help

contractors select superior entry modes to penetrate potential economies (either

developing countries or developed countries) and provide services to different types of

owners (e.g., local private, home private, local public, or international organization).

8

1.6 Relevance

With the entry mode taxonomy and entry mode selection model developed in this

research, contractors who have already developed a presence in international markets can

review and adjust the portfolio of their overseas business and entry strategies under

implementation.

These tools are especially useful for contractors who are just beginning to explore

overseas business opportunities or for global players who are expanding geographically

to new markets to choose entry modes from scratch.

Economies are becoming more global and companies can no longer count on

having domestic markets protected by tariffs and other import barriers since foreign

competitors can always find ways to leap such barriers. Contractors remaining at home,

when threatened by new entrants from abroad, can also gain insights from this research

for developing their competitive or cooperative strategies regarding market entrants.

Although this research is focused on the contractors’ perspective, government

policy makers can obtain important information from the results when forming or

reforming regulations and policies to encourage or control entry of foreign contractors, or

encourage local contractors to expand their business overseas.

1.7 Reader’s Guide

Chapter 1 provided an overview of this thesis, identified the problems and scope

of the thesis, and presented the research methodology used. Chapter 2 details the research

methodology and techniques used to achieve the objectives. Chapter 3 reports the major

findings from literature in disciplines of international business, strategic management,

and international construction in relation to international market entry. Chapter 4 reviews

the internationalization process of the global construction market, and identifies the

9

current trends in market entry and entry mode selection. Chapter 5 provides a

comparative analysis of case studies to define and characterize basic entry modes for

international construction markets, and evaluates the taxonomy with a survey of

practitioners. The feasibility of each entry mode regarding selected major construction

markets is also investigated. Chapter 6 examines the setting characteristics and effects of

each entry mode and groups them according to these dimensions. How different basic

entry modes can be combined or sequenced is also empirically investigated. Chapter 7

reviews multiple schools of theories to build hypotheses which associate internal and

external factors to entry mode selection. In Chapter 8, the hypotheses are tested with

binary logistic regression analysis and a model is developed for entry mode selection.

Chapter 9 concludes the thesis with a summarization of major findings and contributions

of the research, as well as the identification of topics for future research. The appendices

at the end of this thesis include qualitative and quantitative data to support this research

along with the survey instrument.

10

CHAPTER 2

RESEARCH METHODOLOGY

This chapter first generally introduces research methods (Section 2.1), and then

presents the methodology selected to achieve the purpose of this research (Section 2.2).

Research techniques used in the research process are detailed in Section 2.3.

2.1 Introduction

A research methodology sets out and justifies the techniques adopted for the

collection, analysis, and interpretation of data. Numerous and diverse research strategies

have been practiced in construction related areas (see Figure 2.1).

Figure 2.1: Various Research Paradoxes and Typologies Used in Construction

11

Research can be quantitative or qualitative (Fellows and Liu 1997). Quantitative

approaches seek to gather factual data and to study relationships between facts, and how

such facts and relationships accord with theories and the findings of any previously

executed research documented in the literature. Qualitative approaches seek to gain

insights and to understand people’s perceptions of the ‘world’ – whether as individuals or

groups. Qualitative research is typically a precursor to quantitative research.

Research can be exploratory, hypothesis testing, or problem solving (Phillips and

Pugh 2000). Exploratory research is involved in tackling a new problem, issue, or topic.

In this research, the idea cannot be formulated very clearly at the outset and one of the

aims is to develop new theories. Hypothesis testing research pursues the limits of

previously proposed generalizations. This is a basic research activity and one that

proceeds along easily recognizable lines. Hypothesis testing research is more likely to

take place in a structured environment with clear methodologies and measurement

criteria. Third, problem-solving research is one where a problem from practice is

identified and all intellectual resources are brought to bear upon the solution. Here, the

problem has to be defined and the method of solution has to be discovered.

More paradoxes and typologies than those listed in Figure 2.1 can be found in

general or construction management-related literature. Nevertheless, each type of study

performs a particular function and should be selected according to the nature of the issues

or questions to be addressed; the extent of existing knowledge and previous research; the

resources and time available; and the availability of suitably experienced staff to

implement the design (Hakin 2000).

This research involves multiple objectives. Some of them involve qualitative

questions (e.g., the definition of entry modes), while others are more quantitative (e.g.,

the development of the entry mode selection model). Therefore, this research uses a

hybrid approach of both quantitative and qualitative components. Entry strategy for

international construction markets is still a new issue in the construction management

12

research field (refer to Chapter 3), so this research primarily takes an exploratory

approach. However, since some theories can be borrowed from general business and

economics to approach entry mode selection issues in the construction industry, a

hypothesis testing approach is used.

2.2 Research Process

Based on the previous review of research methods and methodologies in general,

and especially those utilized by previous successfully implemented research in the

construction management field, together with thorough consideration of the purpose and

constraints involved in this specific research topic, the following research process was

developed (see Figure 2.2).

13

Research objective

definition

Literature review

(Chapter 3)

Archival analysis

(Chapter 4)

Market entry issues

(Chapter 4)

Comparative case studies

(Chapter 5)

Task 1:

Defining research

questions

Industry survey

(Chapter 5)

Basic entry mode definitions

(Chapter 5)

Task 2:

Defining entry

modes

Differentiating entry modes

(Chapter 6)

Hypothesis building

(Chapter 7)

Hypothesis testing

(Chapter 8)

Task 3:

Selecting entry

modes

Result interpretation

(Chapter 8)

Figure 2.2: Research Process

2.2.1 Task 1: Define Research Questions

The goal and scope of this research necessitate input from multiple fields, and

those emphasized in this specific research are international construction, strategic

management, (global) marketing strategy, and international business. Each of these fields

has a large body of literature. To command the mainstream of each field, this research

14

began with an extensive literature review.

A large number of academic journals,

industry journals, books, reports, proceedings, theses, laws and regulations, newspapers,

and web pages were reviewed, documented, analyzed, synthesized, and compared. The

literature review is also a source of data and information for the other research activities.

Anecdotal information was documented for later comparative case studies to define entry

modes. It should be noted that the literature review process was a concurrent activity

throughout the entire research process. The latest findings or information in related areas

were continuously monitored to incorporate new ideas or avoid potential overlap.

One of the conclusions from the literature review was that entry mode selection is

an important and extensively studied strategic issue in international business but it

received very little attention in international construction research. This led to the

following questions:

1) Is entry mode selection a critical issue in construction?

2) If it is important, are the findings about entry mode selection in general

business equally applicable in the construction industry, so no specific

research is needed?

To address these questions, this research reviews the globalization process of the

construction industry, studies the current status / trends empirically, and analyzes

comments from industry leaders regarding international market entry. It is found that

entry mode selection is also a very important issue in international construction industry.

By assuming that, as a specific industry, construction has characteristics that necessitate

findings about entry mode selection from other industries to be adapted to apply in this

industry, two research questions were proposed:

1) What are the entry modes that international contractors use to enter selected

overseas markets?

2) What are the internal and external factors influencing entry mode selection

and how do they influence the selection?

In other words, this research addresses two basic issues: entry mode definition and entry

mode selection.

15

2.2.2 Task 2: Entry Mode Definition

The study started with existing taxonomies of entry modes in general international

business, and then cases regarding each entry mode from international construction

practices were sought. Special cases that involve patterns of entry that did not match any

well defined entry modes in general business were also examined. In total, over 90 cases

were collected that jointly show the structure, formation process, merits and demerits for

a taxonomy of entry modes specifically for international construction markets. These

entry modes were further analyzed in terms of their setting characteristics (e.g.,

cooperative or competitive, permanent investment or contractual based) and their effects

(e.g., risk, control, and flexibility). Based on their similarities and differences in terms of

these setting characteristics and effects, they were grouped. One grouping scheme

provides a dichotomy of permanent entry versus mobile entry. This dichotomy was

identified as a critical selection issue for the following research step.

2.2.3 Task 3: Entry Mode Selection

The hypothesis testing method was used for entry mode selection. Theories that

may potentially influence the selection between permanent entry and mobile entry were

examined and streamlined to identify factors that can influence the selection. Hypotheses

centering on these factors were developed. Multiple sources of data were collected to test

the hypotheses and develop a model using the binary logistic regression technique. This

model that describes under what scenarios contractors will choose which entry mode is

further analyzed to check if it is a normative model with a t-test. A normative model

means that if contractors use the entry mode suggested by the model, better performance

can be achieved. The data collection and binary logistic regression analysis are

introduced in Section 2.3. Based on the results of the hypothesis testing and model

building, managerial implications were developed.

16

2.3 Research Techniques

Major techniques involved in the above research process are described in this

section.

2.3.1 Data Collection

Empirical research into market entry strategies within the construction industry is

limited. A major challenge in performing this type of research is the “data gap”. Data on

international construction companies and country markets are frequently insufficient and

sometimes suspicious since:

1) Countries use different national accounting systems;

2) Many transactions can escape official statistics, especially private sector

transactions;

3) It is difficulty to determine the time of revenue;

4) Local subcontracting makes revenue figures uncertain;

5) It is difficult to decide sample size; and

6) Low response rate / delay occurs in data collection survey.

For example, the following problems exist with data from the popular

Engineering News Record (ENR) top international contractor data:

1) Much of the ENR data is obtained by annual self-reporting surveys completed

by participating firms. Definitional problems and the self-interests of the

firms to appear in the best possible light may in some case convey misleading

information relating to individual firm rankings (U.S. Department of

Commerce 1984).

2) ENR consolidates subsidiary data with data of the subsidiary’s parent

company, even though the subsidiary may dominate the business of the

parent company and be located in a country other than that of the parent

company (U.S. Department of Commerce 1984).

17

3) Only the Top 225 international and global contractors are reported.

4) ENR data focuses on revenue with no profit figures provided.

5) ENR systematically overstates the aggregate volume of construction activity

by double-counting the subcontracts already accounted for by main contracts

awarded to other large firms (Linder 1994). This leads to an upward bias.

Even though these problems exist, the ENR data on international construction is clearly

the best of its kind available and useful for capturing trends over time and relative

distributions among firms and countries (Linder 1994; U.S. Department of Commerce

1984).

A multi-source strategy is used to bridge the data gap. More reliable conclusions

are expected by using comprehensive data sources and the complementation between

different data sources. Types of data that are used in this research include:

1) Country specific data (e.g., national cultural scoring by Hofstede);

2) Industry-based data (e.g., construction spending of each country reported by

ENR);

3) Firm specific data (e.g., international revenue of leading construction firms

reported by ENR); and

4) Specific survey-based data (see Section 2.3.3).

2.3.2 Case Study

A case study encourages an in-depth investigation of particular instances within

the research subject (Fellows and Liu 1997). The method is very useful in research areas

where (1) the research question addresses ‘how’ or ‘why’; (2) there is little control of the

events; and (3) the focus of the study is on contemporary events (Yin 2003). Case study

research may combine a variety of data collection methods of ethnography, action

research, interviews, and scrutiny of documentation (Fellows and Liu 1997). The sampled

18

cases for investigation must be representative to the manifestation or instance of the

research subject.

Jensen and Rodgers (2001) set forth five types of cases studies: 1) snapshot case

studies; 2) longitudinal case studies, 3) pre-post case studies, 4) patchwork cases studies

(combination of preceding case studies methods), and 5) comparative case studies.

Among them, comparative case studies examine a set of multiple cases studies of

multiple research entities for the purpose of cross-unit comparison. Case studies are not

representative of entire populations, and their conclusions are generalized to a theory.

Because of this, case selection should be theory-driven: the cases must represent

dimensions of certain theory. Case studies can be used either for theory testing (pattern

matching) or theory building (explanation building).

In this research, to establish a taxonomy of entry modes specifically for the global

construction industry, existing definitions and taxonomies of market entry modes

pertaining to general international business are the “theories” to be tested. The research

begins with reviewing entry modes defined in the general business discipline and find

representative cases from international construction to match them, and also try to collect

cases that involve patterns that existing entry modes do not match well and define them

as entry modes unique to the construction industry. The cases supporting a certain entry

mode or pattern are further compared with each other to define and characterize each

entry mode in the context of international construction. Some entry modes may not exist

in international construction (they are not matched by any cases collected in this

research), and they are therefore rejected from the taxonomy. Through this method, a

taxonomy of market entry modes specific to the international construction sector is

developed.

Data for case studies in this research mainly come from analysis of documentation

including books, industry journals, academic journals, newspapers, and contractors’ web

19

sites. These cases are about leading international contractors’ market entry related actions

and decisions.

2.3.3

Survey

A survey is used to evaluate specific attitudes or behaviors. It typically involves

designing and administering a questionnaire (Bordens and Abbott 1996).

There are two types of questionnaire items, open-ended and restricted (or

close-ended) items. The former allows the participant to provide a response in his or her

own words, while the later provides alternatives in a logical order, e.g., a rating scale.

The questions must be organized into a coherent, visually pleasing format. Most

questionnaires include questions designed to assess the characteristics of the participants

(or demographics) that can be used as predictor variables to determine whether

participant characteristics correlate with, or predict response to, other questions in the

survey. Reliability of the questionnaire must be assured by methods such as repeated

testing and split half test.

After developing the questionnaire, the researcher can choose to mail it to

subjects (mail survey), telephone participants to ask the questions directly (telephone

survey), or conduct face-to-face interviews (structured interview survey). Without a

questionnaire, unstructured interview surveys can be conducted, which in comparison

with a structured interview survey, is more flexible, but not as easy to summarize and

analyze (Bordens and Abbott 1996). Proper sampling is a crucial aspect of a sound

survey research methodology. Regardless of the administration method, the sample

should be representative of the population of interest. Sampling technique can be chosen

from simple random sampling, stratified sampling, proportionate sampling, systematic

sampling, and cluster sampling, among others.

20

2.3.4 Statistic Analysis

Statistic analysis is widely used in hypothesis testing research. The structure of

the main knowledge body of statistics is depicted in Figure 2.3. This research, based on

theoretical reasoning, develops a set of hypotheses centering on different independent

variables regarding their impacts on entry mode selection. The categorical nature of the

dependent variable (permanent entry versus mobile entry) and the hypothesized

relationships indicate that binary (or binomial) logistic regression analysis is an

appropriate analytical technique (highlighted in Figure 2.3).

Binary logistic regression is used when the dependent variable is a dichotomy and

the independent variables are of any type. Logistic regression can be used to predict a

dependent variable on the basis of independents; determine the percent of variance in the

dependent variable explained by the independents; rank the relative importance of

independents; and assess interaction effects. Logistic regression is a robust process since:

1) It does not assume a linear relationship between the dependent variable and

the independent variables;

2) The dependent variable need not be normally distributed;

3) The dependent variable need not be homoscedastic for each level of the

independents;

4) It does not require that the independents be an interval; and

5) It does not require that the independents be unbounded.

But like Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression, it requires no perfect multicollinearity.

It also needs a large of sample size.

2.4 Summary

A methodology utilizing both exploratory and hypothesis testing approaches was

designed for this research. Comparative case studies are used to define entry modes and

21

develop a market entry mode taxonomy specifically for international construction. Binary

logistic regression is used to analyze a large sample of data of different sources to test

hypotheses developed with extensive theoretical reasoning and develop a model for entry

mode selection.

22

Figure 2.3: The Structure of the Main Knowledge Body of Statistics

23

CHAPTER 3

LITERATURE REVIEW

Day (1986) suggests that there are two major managerial decisions to make when

considering market entry: 1) the timing of market entry (e.g., being a pioneer; being a fast

follower or an early entrant; or being a late entrant), and 2) the mode of the market entry

(e.g., internal development, acquisition, or joint venture). In addition to these two key

decision areas, Karakaya and Stahl (1991) claimed that one must consider the type and

magnitude of barriers to market entry and plan a strategy to deal with these barriers as

well as to create barriers to entry for competition once in the market. Root (1987)

contended that market entry strategies require five decisions: 1) the choice of a target

market; 2) the objectives and goals in the target market; 3) the choice of an entry mode to

penetrate the target country; 4) the marketing plan to penetrate the target market; and 5)

the control system to monitor performance in the target market. In fact most literature on

international market entry focuses on four issues: 1) entry barriers; 2) market selection; 3)

entry timing; and 4) entry mode selection. In addition to examining international market

entry as a strategic issue, some research focuses on the organizational aspect. The major

concepts involved in international market entry and the interrelationships between them

is depicted in Figure 3.1

24

Figure 3.1: The Framework for Contextual Issues for International Market Entry

3.1 Entry as a Strategic Issue

Market entry is a corporate level issue, and entry strategy is the strategic issue

with the most far-reaching ramifications for all levels of strategy (Yip 1982). This section

reviews the general literature about strategy from a construction industry perspective.

3.1.1 Strategic Planning and Management: a Construction Perspective

According to Betts and Ofori (1992), the long term survival of most large

organizations depends upon effective strategic management. The history of strategy and

strategic management can be traced back to ancient Greece (Chinowsky and Meredith

2000). However, research by the academic community has occurred primarily in the past

four decades (Cheah 2002), and this discipline centering on ‘strategy’ has not been

25

evolving into a consistent and well structured knowledge body. There are many apparent

disagreements among leading theorists in the field of strategy (Price and Newson 2003).

De Wit and Meyer (1998) stated that “there are strongly differing opinions on most of the

key issues within the field and the disagreements run so deep that even a common

definition of the term strategy is illusive.” One major reason is that the strategy discipline

was developed by borrowing from different quantitative or qualitative disciplines,

including economics (especially industrial economics), finance, psychology, sociology,

and military arts (Cheah 2002; Chinowsky and Meredith 2000).

Effective strategic management is especially important for construction

organizations, which have to provide increasingly complex projects within a highly

turbulent and competitive business environment (Price and Newson 2003). However,

literature on strategic management is limited in the context of civil and architectural

engineering, which has a project management tradition (Chinowsky and Meredith 2000;

Messner 1994). Observing that the project management concept is the central focus for

researchers, practitioners, and academic programs, Chinowsky and Meredith (2000)