file - EBF Groningen

advertisement

Managerial accounting is the process of measuring, analyzing and reporting financial and

nonfinancial information that helps managers that helps managers make decisions to fulfill the goals

of an organization. Managers use management accounting information to:

1. Develop, communicate and implement strategies

2. Coordinate product design, production and marketing decisions and evaluate a company’s

performance

Financial accounting focuses on reporting to external users including investors, creditors and

governmental agencies. Financial statements must be based on GAAP/IFRS.

Strategic Cost Management focuses specifically on the cost dimension within a firm’s overall

strategy.

The Value Chain is the sequence of business functions by which a product is made progressively

more useful to customers.

Strategy and Management Accounting

Strategic cost management – focuses specifically on the cost dimension within a firm’s

overall strategy.

Management accounting helps answer important questions such as:

- Who are our most important customers, and how do we deliver value to them?

- What substitute products exist in the marketplace, and how do they differ from our own?

- What is our critical capability?

- Will we have enough cash to support our strategy or will we need to seek additional

sources?

Basic Cost Terminology

Cost: sacrificed resources to achieve a specific objective

Actual cost: a cost that has occurred

Budgeted cost: a predicted cost

Cost object: anything of interest for which a cost is desired

Cost accumulation: a collection of cost data in an organized manner

Cost assignment: a general term that includes gathering accumulated costs to a cost object this

includes:

Tracing accumulated costs with a direct relationship to the cost object,

Allocation accumulated costs with an indirect relationship to a cost object.

Direct cost can be conveniently and economically traced to a cost object.

Indirect cost cannot be conveniently or economically traced to a cost object. Instead of being traced,

these costs are allocated to a cost object in a rational and systematic manner.

Variable Costs

Total Dollars

Cost per Unit

Change in proportion

with output

Unchanged in relation to output

More output = More cost

Fixed Costs

Unchanged in relation to

output

Change inversely with output

More output = lower cost per unit

Cost driver: a variable that causally affects costs over a given time span.

Relevant range: the band of normal activity level (or volume) in which there is a specific relationship

between the level of activity (or volume) and a given cost.

Unit costs (or average cost) should be used cautiously. Because unit costs change with a different

level of output or volume, it may be more prudent to base decisions on a total dollar basis.

- Unit costs that include fixed costs should always reference a given level of output or activity.

- Unit costs are also called average costs.

- Managers should think in terms of total costs rather than unit costs.

Types of product costs (also known as inventoriable costs)

Direct materials – acquisition costs of all materials that will become part of the cost object.

Direct labor – compensation of all manufacturing labor that can be traced to the cost object.

Indirect manufacturing (overhead) – factory costs that are not traceable to the product in an

economically feasible way. Examples include lubricants, indirect manufacturing labor, utilities

and supplies.

Management Accounting Guidelines

Cost-benefit approach is commonly used: benefits generally must exceed costs as a basic

decision rule.

Behavioral and technical considerations – people are involved in decision, not just dollars

and cents.

Managers use alternative ways to compute costs in different decision-making situations:

‘different costs for different purposes’

Learning objectives

1.

classify the types of costs that are incurred by organizations, by distinguishing product costs from

period costs, and direct from indirect costs

2.

identify various concepts of costs, such as opportunity costs, out-of-pocket costs, sunk costs,

differential costs, marginal costs, and average costs

3.

execute a cost-volume-profit analysis and apply alternative cost accounting systems like job-order

costing and activity-based costing

4.

use alternative cost-estimation methods and interpret the behaviour of different cost functions

5.

describe a typical organization’s process of budget administration

6.

distinguish between static and flexible budgets, and execute a variance analysis for direct and

marketing costs for organizations using standard costing

7.

analyze and evaluate the organizational implications of alternative models of responsibility

accounting, transfer pricing and performance measurement

8.

select what accounting information is useful to support internal decision-making, planning and control

decisions

Cost Terminology

- Variable costs: costs that change in total in relation to some chosen activity or output.

- Fixed costs: costs that do not change in total in relation to some chosen activity or output.

- Mixed cost: costs that have both fixed and variable components; also called semi-variable costs.

Linear costs functions illustrated

Criteria for classifying variable and fixed components of a cost

1. Choice of cost object: different objects may result in different classification of the same cost

2. Time horizon: the longer the period, the more likely the cost will be variable

3. Relevant range: behavior is predictable only within this band of activity

Total, average and marginal costs

Total cost (TC) = Fixed Cost (FC) + Variable Cost (VC)

Average cost (AC) = TC/Y AC at first fall as output grows, but as higher levels of output

they increase again.

Marginal cost (MC): additional cost incurred in producing an additional unit of output

- slope of total cost curve = dTC/dY

Average costs vs. marginal costs

AC curve reflects the effects of:

- Spreading out fixed costs (AC>MC at low volume)

- Diminishing returns to scale increase AVC (machine

breakdowns, overtime payments etc.)

Cost estimation methods

1.

2.

3.

4.

Industrial engineering method

Conference method

Account analysis method

Quantitative analysis method

- High-low method

- Regression analysis

Steps in estimating a cost function using quantitative analysis

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

6.

Choose the dependent variable (the cost to be predicted).

Identify the independent variable or cost driver.

Collect data on the dependent variable and the cost driver.

Plot the data.

Estimate the cost function using the high-low method or regression analysis

Evaluate the cost driver of the estimated cost function

High-low Method

- Simplest method of quantitative analysis

- Uses only the highest and lowest observed values

High-low Method Plot

Steps in the High-Low Method

1. Calculate variable cost per unit of activity

Variable

Cost per

=

{

Unit of Activity

Cost associated with

highest activity level

Highest activity level

-

Cost associated with

lowest activity level

}

Lowest activity level

2. Calculate total fixed costs

Total Cost from either the highest or lowest activity level

- (Variable Cost per unit of activity X Activity associated with above total cost)

Fixed Costs

3. Summarize by writing a linear equation

Y = Fixed Costs + ( Variable cost per unit of Activity * Activity )

Y = FC + (VCu * X)

Regression Analysis

Regression analysis is a statistical method that measures the average amount of change in

the dependent variable associated with a unit change in one or more independent variables.

Is more accurate than the high-low method because the regression equation estimates costs

using information from all observations; the high-low method only uses two observations.

Sample regression model plot

Alternative Regression Model Plot

Regression Terminology

- Goodness of fit (R2): indicates the strength of the relationship between the cost driver and costs.

- Residual term: measures the distance between actual cost and estimated cost for each observation.

Criteria to evaluate alternative cost drivers:

1. Economic plausibility

2. Goodness of fit

3. Significance of the independent variable

Nonlinear Cost Functions

1.

2.

3.

4.

Economies of scale

Quantity discount

Step cost functions – resources increase in “lot sizes”, not individual units

Learning curves – labor hours consumed decrease as workers learn their jobs and become

better at them

5. Experience curve – broader application of learning curve that includes downstream activities

including marketing and distribution

Nonlinear Cost Functions Illustrated

Learning Curve

- A systematic relationship between the amount of experience in performing a task and the time

required to carry out the task.

- The average time per task declines by a constant percentage each time the quantity of tasks

doubles

- Mathematical relationship

Yx cumulative average time per unit

Yx aX b

b

ln(%learning)

ln 2

X cumulative number of units produced

a time required to produce first unit

b rate of learning

Types of Learning Curves

- Cumulative average-time learning model: cumulative average time per unit declines by a constant

percentage each time the cumulative quantity of units produced doubles.

- Incremental unit-time learning model: incremental time needed to produce the last unit declines by

a constant percentage each time the cumulative quantity of units produced doubles.

The Ideal Database

1. The database should contain numerous reliably measured observations of the cost driver and the

costs.

2. In relation to the cost driver, the database should consider many values spanning a wide range.

Data Problems

- The time period for measuring the dependent variable does not match the period for measuring the

cost driver.

- Fixed costs are allocated as if they are variable.

- Data are either not available for all observations or are not uniformly reliable.

- The relationship between the cost driver and the cost is not stationary.

- Extreme values of observations occur from errors in recording costs.

Foundational Assumptions in CVP

Changes in productions/sales volume are the sole cause for cost and revenue changes.

Total costs consist of fixed costs and variable costs.

Revenue and costs behave and can be graphed as a linear function (a straight line).

Selling price, variable cost per unit, and fixed costs are all known and constant.

In many cases only a single product will be analyzed. If multiple products are studied, their

relative sales proportions are known and constant.

The time value of money (interest) is ignored.

Basic Formula

CVP: Contribution Margin

Manipulation of the basic equations yields an extremely important and powerful tool

extensively used in cost accounting: contribution margin (CM).

Total contribution margin equals revenue less variable.

Contribution margin per unit equals unit selling price less unit variable costs.

Contribution margin percentage is the contribution margin per dollar/euro of revenue.

Cost-Volume-Profit Equation

Revenue – Variable Costs – Fixed costs = Operating Income

(Selling price*Sales Quantity) – (Unit Variable Costs*Sales Quantity) – Fixed Costs = Operating Income

Breakeven Point

At the breakeven point, a firm has no profit or loss at the given sales level.

Sales – Variable Costs – Fixed Costs = 0

Calculation of breakeven number of units

Breakeven Units = Fixed Costs / Contribution Margin per Unit

Calculation of breakeven revenues

Breakeven Revenue = Fixed Costs / Contribution Margin Percentage

Breakeven Point, extended: Profit Planning

The breakeven point formula can be modified to become a profit planning tool.

- Profit is now reinstated to be the BE formula, changing it to a simple sales volume equation.

- Quantity of Units = (Fixed Costs + Operating Income)

Required to be sold Contribution Margin per Unit

CVP: Graphically

Cost = 2000+120x

Revenue = 200x

Costs = revenue where 2000 + 120x = 200x

2000 = 80x

2000/80 =25

Profit should be 2000

2000 profit + 2000 fixed costs

= 4000/80

=50

Contribution margin per product = 80

CVP: PV-Graph

CVP and Income Taxes

After-tax profit can be calculated by:

Net Income = Operating Income * (1 – tax rate)

Net income can be converted to operating income for use in CVP equation

Operating income = Net Income / (1 – tax rate)

Margin of Safety

One indicator of risk, the margin of safety (MOS), measures how far actual revenues can fall

below budgeted revenues before the breakeven point is reached

MOS = Budgeted revenues – Break even revenues

The MOS ratio removes the firm’s size from the output, and expresses itself in the form of a

percentage

MOS Ratio = MOS / Budgeted revenues

Operating Leverage

The degree of operating leverage (DOL) is the effect that fixed costs have on changes in

operating income as changes occur in units sold and contribution margin.

DOL = Contribution Margin/Operating Income

Notice these two items are identical, except for fixed costs.

What is the relationship beween DOL and break-even (BE)? Draw a graph

(Price-variable cost) * Quantity / ((price-variable cost) * Quantity) – Fixed cost

DOL is a function of Quantity, thus the operating leverage is different at different levels of output

Operating leverage is a measure of how sensitive net operating income is to a given percentage change in

sales.

1. Contribution Margin. Contribution margin is the amount remaining from sales revenue after

variable expenses have been deducted. It contributes towards covering fixed costs and then

towards profit.

2. Degree of operative leverage * percentage in sales = percentage change in operating income

DOL

+1

0

Q

BE

= F/(p-v)

Operating leverage and risk

Operating leverage has the potential to increase returns but also increases risk.

Once the break-even point is reached, sales contribute to profits much more than they would

if more of the costs were variable.

However, if sales fall short of expectations, fixed costs still have to be covered. Thus,

operating leverage also increases bankruptcy risk of the firm.

Cost Terminology

Cost pool: any logical grouping of related cost objects

Cost-allocation base: a cost driver is used as a basic upon which to build a systematic method of

distributing indirect costs. (For example, let’s say that direct labor hours cause indirect costs to

change. Accordingly, direct labor hours will be used to distribute or allocate costs among objects

based on their usage of that cost driver.)

Allocation of overhead

Most plants or departments produce/deliver a diverse set of outputs, not a single homogeneous

product/service.

Volume (i.e. capacity) is measured not in terms of output but rather in terms of a common input

such as direct labor hours, machine time, or direct labor euros.

The Budgeted volume or denominator level is estimated at the beginning of the accounting

period (normally the fiscal year).

Allocation of overhead Terminology

BOH = Budgeted Overhead

VOH = Variable Overhead

FOH = Fixed Overhead

OHR = Overhead Rate (total)

VOHR = Variable Overhead Rate

FOHR = Fixed Overhead Rate

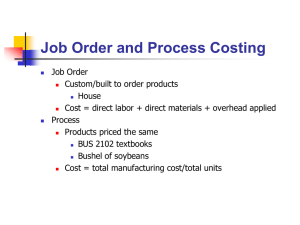

Costing Systems

Job-costing: system accounting for distinct cost objects called jobs. Each job may be different

from the next, and consumes different resources. (E.g. customer support, aircraft,

advertising, consulting or auditing engagement)

Process-costing: system accounting for mass production of identical or similar products. (E.g.

Oil refining, orange juice, soda pop)

Costing Approaches

Actual costing – allocates:

- Indirect costs based on the actual indirect-cost rates times the actual activity consumption

Normal costing – allocates:

- Indirect costs based on the budgeted indirect-cost rates times the actual activity consumption

Both methods allocate direct costs to a cost object the same way: by using actual direct-cost rates

times actual consumption

7-Steps Job Costing

1. Identify the job that is the chosen cost object.

2. Identify the direct costs of the job.

3. Select the cost-allocation base(s) to use for allocating indirect costs to the job.

4. Match indirect costs to their respective cost-allocation base(s).

5. Calculate an overhead allocation rate (OHR).

Budgeted Manufacturing =

Budgeted Manufacturing Overhead Costs

Overhead Rate

Budgeted Total Quantity of Cost-Allocation Base

6. Allocate overhead costs to the job:

Budgeted Allocation Rate * Actual Base Activity For the Job

7. Compute total job costs by adding all direct and indirect costs together

Job Costing Overview

Flow of Costs Illustrated

Accounting for Overhead

Actual costs will almost never be equal to budgeted costs.

- If Overhead Control > Overhead Allocated, this is called Underallocated Overhead

- If Overhead Control < Overhead Allocated, this is called Overallocated Overhead

This difference will be eliminated in the end-of-period adjusting entry process, using one of

three possible methods.

The choice of method should be based on such issues as materiality, consistency, and

industry practice.

Three Methods for Adjusting Over/Underapplied Overhead

Adjust allocation rate approach: all allocations are recalculated with the actual, exact

allocation rate.

Proration approach: the difference is allocated between cost of goods sold, work-in-process,

and finished goods based on their relative sizes.

Write-off approach: the difference is simply written off to costs of goods sold.

Allocation of overhead

Simple Methods (less accurate) Complex methods (more accurate)

Broad Averaging

Historically, firms produced a limited variety of goods while their indirect costs were

relatively small.

Allocating overhead costs was simple: use broad averages to allocate costs uniformly

regardless of how they are actually incurred.

Consequence: overcosting and undercosting

Over-/Undercosting and Cross-subsidization

Overcosting: a product consumes a low level of resources but is allocated high costs per unit.

Undercosting: a product consumes a high level of resources but is allocated a low cost per

unit.

The results of overcosting one product and undercosting another:

- The overcosted product absorbs too much cost, making it seem less profitable than it really is

- The undercosted product is left with too little cost, making it seem more profitable than it really is

An example: Plastim

Criticism of traditional allocation method

Assumes all overhead is volume-related

Organization-wide or departmental rates all related to single indirect-cost pool

Departmental focus, not process focus

Focus on cost incurred, not cause of costs

Consequences:

- Cost defined less accurately than possible

- Biased and unfair cost allocation

Activity-Based Costing (ABC)

Purpose of ABC:

Allocation of indirect costs based on causal activities

Attempts to identify “direct” link between cost and cost object

Results in better (i.e. more accurate) allocation

Yet, ABC does not provide a “true” cost

Traditional vs ABC allocation method

Traditional allocation method:

Costs

Products

Activity-Based Costing:

Costs

Activities

First stage

Products

Second stage

Plastim and ABC Illustrated

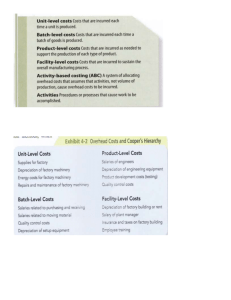

ABC Cost Hierarchy

A cost hierarchy is a categorization of costs into different costs pools on the basis of the different

types of cost drivers (cost-allocation bases) or different degrees of difficulty in determining cause-andeffect relationships

Not all costs are volume related

Cost-hierarchy:

- Output unit-level

- Batch-level

- Product or Service-sustaining level

- Facility-sustaining level

Advantages of ABC/ABM

Shifts focus from managing costs to managing activities

Aids in recognizing, measuring and controlling complexity

Promotes understanding of why costs are incurred

Provides better (e.g. more accurate) cost allocation information

When is ABC most beneficial?

Significant amounts of indirect costs are allocated using only one or two cost pools

All or most costs are identified as output unit-level costs

Products make diverse demands on resources because of differences in volume, process steps, batch

size or complexity

Products that a company is well suited to make and sell show small profits while products for which a

company is less suited show large profits

Complex products appear to be very profitable and simple products appear to be losing money

Operations staff have significant disagreements with the accounting staff about the production costs

and marketing products and services.

ABC and accuracy: trade-offs

Chapter 15: Allocating Costs of a Supporting Department to Operating Departments

Supporting (service) department – provides the services that assist other internal departments in the

company

Operating (production) department – directly adds value to a product or service

Direct Method

Allocates support costs only to operating departments.

Direct method does not allocate support-department costs to other support departments.

Direct Allocation Method

Step-Down Method

Also called the sequential allocation method

Allocates support-department costs to other support departments and to operating departments in a

sequential manner

Partially recognized the mutual services provided among all support departments

Step-Down Allocation Method Illustrated

Reciprocal Method

Allocates support-department costs to operating departments by fully recognizing the mutual services

provided among all support departments.

Reciprocal method fully incorporates interdepartmental relationships into the support-department

cost allocation.

Reciprocal Allocation Method (Linear Equations) Illustrated

Five-step decision-making process

Roles of accounting information

Decision-making role of accounting information:

- Reduce ex-ante uncertainty

- Improve judgment and decision-making

Decision-control role of accounting information:

- Motivate, evaluate and reward

- Help to mitigate so-called ‘agency’ problems (i.e. dysfunctional behavior)

Interdependencies between the two roles

- Information and incentives are inextricably linked

Crucial accounting information attributes

1.

2.

3.

Accuracy

- Ability to reliably measure economic activities

- Freedom from bias

Timelines

Relevance

- ‘different costs for different purposes’

Key features of relevant information

Different alternatives can be compared by examining differences in expected total future revenues

and future costs:

- Key questions: What difference will it make? What are the opportunity costs?

- Opportunity costs: benefits foregone by choosing the best alternative rather than the next best nonselected alternative.

Sunk (historical) costs may be helpful as a basis for making predictions. However, past costs

themselves are always irrelevant when making decisions.

- Beware: Sunk costs can be relevant for decision-control!

Pay attention to excess or surplus capacity

Identify available from unavailable costs

Due weight must be given to qualitative factors and quantitative non-financial factors

Two potential problems in relevant-cost analysis

Watch out for incorrect general assumptions, like:

- All variable costs are relevant

- All fixed costs are irrelevant (it applies only within relevant range)

Misleading unit-cost data

- Fixed costs per unit at different output levels

- Keep focusing on total revenues and total costs,

Role of product costs in pricing

Understanding how to analyze product costs in crucial for pricing decisions:

- Even when prices are set by overall market supply and demand forces and the firm has little or no

influence on product prices, management still has to decide the best mix of products to manufacture

and sell.

Economic pricing model

Limitations of economic pricing model

1.

2.

3.

Firm’s demand and marginal revenue curves are difficult to determine with precision

The marginal cost, marginal revenue paradigm is not valid for all forms of market organization

Cost accounting systems are not designed to measure the marginal charges in cost incurred as

production and sales increase by unit. To measure marginal cost would entail a very costly information

system:

Role of accounting product costs in pricing

Cost-plus pricing

Price = cost + (markup percentage x cost)

Cost base may vary:

- Full cost

- Variable cost

Full cost pricing formula

Advantages:

- In the long run, the price must cover all costs and a normal profit margin (stability and cost recovery)

- Full (or absorption) cost information is provided by a firm’s cost-accounting system, because it is

required for external financial reporting (simplicity)

- Full cost pricing formulas provide a justifiable price that tends to be perceived as equitable by all

parties (fairness)

- Most firms use full cost for their cost-based pricing decisions

Disadvantage:

- Full costs formula pricing obscure the cost behavior pattern of the firm

Variable cost pricing formula

Advantages:

- Variable-cost data do not obscure the cost behavior pattern by unitizing fixed costs and making them

appear variable.

- Variable cost-data do not require allocation of common fixed costs to individual product lines.

Disadvantages:

- Managers may perceive the variable cost of a product or service as the ‘price floor’.

- Fixed costs may be overlooked in pricing decisions, resulting in prices that are too low to cover total

costs.

The markup rate

Just as prices depend on demand conditions, markup increase with the strength of demand:

- If more customers demand more of a product, then the firm is able to command a higher markup

Markups also depend on the elasticity of demand:

- Demand is said to be elastic if customers are very sensitive to the price, that is, if a small increase in

the price results in a large decrease in the demand.

- Markups are smaller when demand is more elastic.

Markups also fluctuate with the intensity of competition

- If competition is intense, it is more difficult for a firm to sustain a price much higher than its

incremental cost.

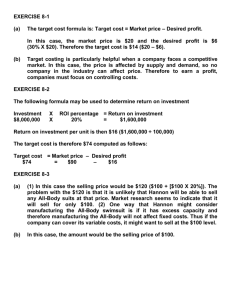

Target costing

Target cost = Target price per unit – Target profit per unit

The target costing process is a system of profit planning and cost management that is price led,

customer focused, design centered and cross-functional

Target costing initiates cost management at the earliest stages of product development and applies it

throughout the product life cycle by actively involving the entire value chain.

Target costing

Target costing vs Standard costing

Value engineering

Value engineering is a systematic evaluation of all aspects of the value chain, with the goal of reducing

costs while improving quality and satisfying customer need.

Managers must distinguish:

- Value-added costs: a cost that, if eliminated, would reduce the actual or perceived value or utility

(usefulness) customers obtain from using the product or service.

Non-value-added costs: a cost that, if eliminated, would not reduce the actual or perceived value or

utility customers obtain from using the product or service. It is a cost the customer is unwilling to pay

for.

Cost incurrence arise when a resource is sacrificed or forgone to meet a specific objective.

- Research and Development

- Design

- Manufacturing

- Marketing

- Distribution

- Customer Support

Locked-in-costs are those costs that have not yet been incurred but which, based on decision that

have already been made, will be incurred in the future (design-in costs).

Cost incurrence and Locked-in costs

Behavioral accounting

Despite the quantitative nature of some aspects of decision making, not all mangers will choose the

best alternative for the firm.

Managers could engage in self-serving behavior such as delaying needed equipment maintenance in

order to meet their personal profitability quotas for bonus consideration.

Let’s focus on behavioral implications of accounting information with regards to accuracy.

Less accurate cost systems

When and why to deliberately measure costs less accurately to improve decision making?

Three forms of less accurate cost systems:

1. Cost biased upward

2. Cost biased downward

3. Cost defined less precisely than is possible

Cost biased upward

Why do some persons set their watch 5 minutes ahead?

- Even though they know that their watch shows biased information, it helps them to overcome their

propensity to be late

Rational in cost accounting is overstate product costs:

- Positive effects on pricing decisions in competitive situations, for instance protection against the

tendency to shave profit margins.

Cost biased downward

Rationale in cost accounting to understate produce costs:

- Target costing: cost standards based on estimates of what an item should cost. In a target costing

system unfavorable variances do not necessarily signify shirking or waste.

- Other rationale: to stimulate the consumption of service

Cost defined less precisely than possible

Rationale:

- To focus attention on areas critical for competitive advantage

- To reduce the occurrence of dysfunctional behavior and effectively increase control.

Example: Activity-Based-Costing (ABC)

Costs of ABC implementation: 2 main sources:

1. The out-of-pocket costs associated with implementing the new system and make it function.

2. Agency costs, i.e. the costs inherently associated with using an agent (e.g. the risk that agents will

use organizational resource for their own benefit)

- from principal-agent theory

Lecture 6

Basic Business Strategies

Product differentiation: an organization’s ability to offer products or services perceived by its customers to be

superior and unique relative to the products or services of its competitors

- Leads to brand loyalty and the willingness of customers to pay high prices

Cost leadership: an organization’s ability to achieve lower costs relative to competitors through productivity

and efficiency improvements, elimination of waste, and tight cost control

- Leads to lower selling prices

The Balanced Scorecard

The Balance Scorecard translates an organization’s mission and strategy into a set of performance

measures that provides the framework for implementing its strategy.

It is called Balanced Scorecard because it balances the use of financial and nonfinancial performance

measures to evaluate performance.

The Financial Perspective

Evaluates the profitability of the strategy

Uses the most objective measures in the scorecard

The other three perspectives eventually feed back into this dimension

The Customer Perspective

Identifies targeted customer and market segments and measures the company’s success in these

segments.

The Internal Business Perspective

Focuses on internal operations that create value for customers that, in turn, furthers the financial

perspective by increasing shareholder value

Includes three sub-processes:

1. Innovation

2. Operations

3. Post-sales service

The Learning and Growth Perspective

Identifies the capabilities the organization must excel at to achieve superior internal processes that

create value for customers and shareholders.

Strategy Map

Features of a ‘Good’ Balanced Scorecard

Tells the story of a firms strategy, articulating a sequence of cause-and-effect relations – the links

among the various perspectives that describe how strategy will be implemented.

Helps communicate the strategy to all members of the organization by translating the strategy into a

coherent and linked set of understandable and measurable operational targets.

Must motivate managers to take actions that eventually result in improvements in financial

performance

o Mainly applies to for-profit firms, but has applications to not-for-profit organizations as well

Limits the number of measures, identifying only the most critical ones

Highlights less-than-optimal trade-offs that managers may make when they fail to consider

operational and financial measures together.

Balanced Scorecard Implementation Pitfalls

Managers should not assume the cause-and-effect linkages are precise: they are merely hypotheses.

Managers should not seek improvements across all of the measures all of the time.

Managers should not use only objective measures: subjective measures are important as well.

Managers must include both cost and benefits of initiatives placed in the balanced scorecard: costs are

often overlooked

Managers should not ignore nonfinancial measures when evaluating employess.

Managers should not use too many measures.

The Management of Capacity

Managers can reduce capacity-based fixed costs by measuring and managing unused capacity.

Unused capacity is the amount of productive capacity available over and above the productive

capacity employed to meet consumer demand in the current period.

Analysis of Unused Capacity

Engineered costs result from a cause-and-effect relationship between the cost driver and the

resources used to produce that output.

Discretionary costs have two part:

o They arise from periodic (annual) decisions regarding the maximum amount to be incurred.

o They have no measurable cause=and effect relationship between output and resources used.

Differences Between Engineered and Discretionary Costs Illustrated

Customer Revenues and Customer Costs

Customer-profitability analysis is the reporting and analysis of revenues earned from customers and

costs incurred to earn those revenues.

An analysis of customer differences in revenues and costs can provide insight into why differences

exist in the operating income earned from different customers.

Firms should be prepared to ask and answer detailed questions about their customer and marketing strategies

to understand customer profitability issues.

Customer Revenues

Price discounting is the reduction of selling prices to encourage increases in customer purchases.

o Lower sales price is a trade-off for larger sales volumes.

Discounts should be tracked by customers and salespersons.

Customer Cost Analysis

Customer cost hierarchy categorizes costs related to customers into different cost pools on the basis of

different:

Types of drivers

Cost-allocation bases

Degrees of difficulty in determining cause-and-effect or benefits-received relationship

Customer Cost Hierarchy Example

1.

2.

3.

4.

5.

Customer output unit-level costs

Customer batch-level costs

Customer-sustaining costs

Distribution-channel costs

Corporate-sustaining costs

Other Factors in Evaluating Customer Profitability

Likelihood of customer retention

Potential for sales growth

Long-run customer profitability

Increases in overall demand from having well-known customers

Ability to learn from customers

Customer Lifetime Value

Customer Lifetime Value (CLV)

CLV with Churn

Churn rate (1-r): proportion of contractual customers or subscribers who leave a supplier during a given time

period.

In short: if we assume that the retention rate and CF is constant over time

Sales Variances

Level 1: Static-budget variance – the difference between an actual result and the static-budgeted

amount.

Level 2: Flexible-budget variance – the difference between an actual result and the flexible-budgeted

amount

Level 2: Sales-volume variance

Level 3: Sales-quantity variance

Level 3: Sales-mix variance

Sales-Mix Variance

Measures shifts between selling more or less of higher or lower profitable product.

Sales-Mix

Variance =

Actual

Actual

Units of

X Sales-Mix

All

Percentage

Products

Sold

Budgeted

Sales-Mix X

Percentage

Budgeted

Contribution

Margin per Unit

Sales-Quantity variance

Measures shifts between selling more or less total products.

SalesQuantity =

Variance

Actual

Units of All

Products

Sold

Budgeted

Units of all

Products X

Sold

Budgeted

Sales-Mix

Percentage

X

Budgeted

Contribution

Margin per Unit

Sales Variances Summarized

Lecture 7

Responsibility accounting: Various concepts and tools used to measure performance of divisions and

personnel in order to foster goal congruence (or alignment)

Transfer pricing

Definition: a transfer price (TP) is the amount charged when one division of an organization sells goods

or services to another division

Why are transfer prices used?

o Taxation: in international transaction TP policy has implications on tax liabilities and import

duties

E.g. multinational companies have incentives to set TP that increase(decrease)

revenues in low(high) tax couuntries.

o Do not use tax if not indicated in an assignment

Why are TP used?

- Allocation: on the basis of the TP autonomous divisions have to make the decision that is the best

interest of the organization as a whole.

- Performance evaluation: the reported results of a division need to reflect the contribution of the

contribution of the division to the results of the entire organization.

The goal in setting TP is to provide incentives for each of the division managers to act in the company’s

best interest.

A general TP formula to ensure goal congruence:

TP with perfect and imperfect information

With perfect information, opportunity costs are known

With imperfect information: opportunity costs need to be estimated

o Each division tries to maximize its own contribution margin.

o This can lead to suboptimal decisions: the contribution margin of the organization as a whole

might not be maximized.

As proxy of opportunity costs, different TP systems can be adopted:

o Market-based TP

o Cost-based: variable- or full cost TP

o Negotiated TP

The choice of TP method does not merely reallocate total company profits among divisions, but it also

affects the firm’s total profits.

Market-based transfer price

External market-based TP:

o If 1) the good produced externally is the same as the good produced internally, 2) selling

divisions at capacity, and 3) market is perfectly competitive.

Measurement of opportunity costs is complicated by lack of perfect information because:

o There may be no external market (captive division).

o The external market may not be perfectly competitive.

o There may be technological or demand dependence among divisions.

Cost-based transfer price

Variable-cost based TP:

o Appropriate in case of excess capacity, since the opportunity cost component in the TP

formula is zero.

Disadvantages:

o Production department can not recover all costs

o Variable cost might vary with output

o Production department has incentives to classify fixed costs as variable costs.

Full-cost based TP:

o As a plant begins to reach capacity, full-costs provide a closer approximation to opportunity

costs.

Disadvantages

o Opportunity costs overstated

o Production department can transfer inefficiencies to selling department

Negotiated transfer price

Because of opposite interests of buying and selling departments, the outcome can be an agreed TP.

Final agreement of TP between external market price (ceiling) and variable costs (floor).

o The final TP depends on the bargaining power of buying and selling divisions

Thus, negotiations are time consuming and can lead to conflicts

o If transfer pricing becomes sufficiently dysfunctional reorganization of the firm might be the

next suitable option.

Re-cap on transfer pricing

The choice of TP method does not merely reallocate total company profits among divisions, but it also

affects the firm’s total profits.

TP based on opportunity costs gives divisions incentives to take decisions that are in the best interest

of the company as a whole.

When excess capacity exists, the opportunity costs component in the TP formula is zero.

Performance evaluation

Drawback of using Net Income as performance measure:

o No consideration of the investment used to achieve the net income

Problem can be overcome by using ROI type measure:

o ROI focuses on income and investment

o Removes the bias of larger investment over smaller investment.

ROI was developed in DuPont in the early 1900’s as the product of sales margin and capital turnover.

Drawback of using ROI as a performance measure for an investment center:

Problem can be solved by Residual Income.

Performance evaluation (continued)

Residual Income (RI) corrects Net Income for the opportunity cost of capital:

Residual Income = Net Income – (Cost of capital x Investment)

Drawback: larger divisions have larger RI than smaller divisions

o However, it is possible to vary cost of capital according to the risk associated to different

investment centers

Economic Value Added (EVA) is a performance measure developed by the consulting form Stern

Stewart & Co.

EVA is a more sophisticated version of RI adjusted for ‘accounting distortions’.

Primary distortion is related to R&D:

o Under GAAP, R&D is expensed immediately

o To compute EVA, R&D is capitalized and amortized over a number of future accounting

periods.

EVA: The logic behind it

EVA: The formula

EVA: pro’s and con’s

EVA introduces 4 powerful incentives (pro’s)

Growth, but only if investments can earn the cost of capital

Redeploy capital from underperforming operations

Capitalize expenses that have multi-period benefits

Provides details of corporate performance

Disadvantages (con’s)

Complicated computations

Accounting adjustments are prone to gaming and manipulations

Choice of performance measures

Obtaining performance measures that are more sensitive to employee performance in critical for

implementing strong incentives:

o Sensitive measures means that:

1) measures change significantly with the manager’s performance

2) do not change much with changes in factors that are beyond the manager’s control

Timeliness of performance measures depends largely on how critical the feedback is for the:

o Success of the organization

o Specific level of management involved

o Sophistication of the organization

Choice of performance measures (continued)

Other critical issues in performance evaluation:

o How large should the incentive (variable) component be relative to salary?

o Benchmarks and relative performance evaluation

o Subjective versus formula-based performance appraisal

o Managerial time orientation (i.e. myopia)

o Measurement of intangibles (e.g. leadership)

o Environmental and ethical responsibilities

Resource based 21st century enterprise

Identifying the right non-financial drivers

Non-financial ‘Leading’ indicators

Customer satisfaction (i.e. intangible) is not fully reflected in balance sheet financial accounting

measures.

From traditional performance measurement …

Heavy reliance on management intuition and unsophisticated guesses

Fixation on the ‘four buckets’ of the balanced scorecard

Attempting to apply a seemingly endless set of measurement frameworks pushed by consultants

Measurement of an ever-increasing list of Key Performance Indicators to avoid missing anything

important.

To Action-to-Value Framework

Levers of control

Levers of Control (devised by Robert Simons, Harvard):

o Diagnostic Control Systems

o Boundary Systems

o Belief Systems

o Interactive Control Systems

Each lever is important and needs to be monitored

Levers should be interdependent and collectively represent a living system of business conduct.

Diagnostic Control Systems

Diagnostic Control Systems evaluate whether a firm is performing to expectations by monitorting and

evaluating critical performance metrics, including:

ROI, Residual Income, EVA

Operational performance (e.g. quality)

Intangibles (e.g. customer satisfaction)

It must be balanced by the other levers of control in order to avoid or mitigate dysfunctional behavior, like:

Budgetary slack

‘Cooking the books’ (Fraud)

Managerial myopia (‘short-termism’ or ‘tunnel vision’)

Boundary Systems

Boundary Systems describe standards of behavior and codes of conduct expected of all employees.

Highlights actions that are ‘off-limits’

A code of conduct describes appropriate and inappropriate individual behaviors

Belief Systems

Belief Systems articulate the mission, purpose, and core values of a company

They describe the accepted norms and patterns of behavior expected of all managers and employees

with respect to each other, shareholders, customers, and communities.

Intrinsic Motivation: Desire to achieve self-satisfaction from good performance regardless of external

rewards such as bonuses or promotion

Interactive Control Systems

Interactive Control Systems are formal information systems that mangers use to focus organizational attention

and learning on key strategic issues.

Tracks strategic uncertainties that businesses face

Result is ongoing discussion and debate about assumptions and action plans

New strategies emerge from dialogue and critical evaluation of opportunities and threats.

The evolving role of management accounting