Development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping

advertisement

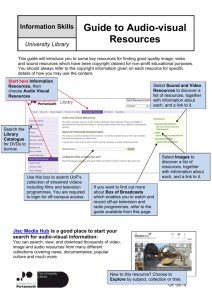

06 597 Development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping Silvia Sanz Blas Isabel Sánchez García Facultad de Economía Universidad de Valencia Abstract Non-store selling represents an opportunity for many companies to diversify their activities in their business and expand their markets. Among all direct methods of purchase, teleshopping is experiencing a great development in recent years thanks, in part, to the advances made in new technologies, allowing that television media becomes a very important tool for trade all over the world. The outstanding broadcasting increase of this kind of programs / advertisements, reflected not only in the channel’s broadcasting time and the apparition of prearranged images, but also in the number of channels (regional, local and sale channels) and companies that offer these services and the access to Internet through television are aspects that encourage the development of this method of purchase. This paper is focused in analysing the evolution of teleshopping along the time with the aim of highlight its importance and identify the future trends. Keywords: television media, teleshopping, new technologies. JEL Code: M31. september · december 2006 · esic market [23] 598 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping 1. Introduction Teleshopping is a commercial non-store formula which has coexisted alongside traditional methods since 1980 in countries such as Italy, France and the United States (Quelch and Takeuchi, 1981). A brief review of the most significant studies in this field shows that early research on Teleshopping focussed attention on the system’s benefits and drawbacks, the target audience and in general the implications of teleshopping itself (Foster, 1981; Martí and Zeilinger, 1982; Quelch and Takeuchi, 1981; Rogers, 1982). The literature on the above aspects of teleshopping was significant but there was an evident lack of research on consumer attitudes towards the new shopping system. By the end of the eighties, studies which focused more on consumer attitudes towards teleshopping began to appear (McKay and Fletcher, 1988) as it was acknowledged that the audience is the potential user of the system and its attitude towards this type of services is of critical importance. The results of this new research facilitated information on the levels of consumer demand for this type of shopping and provided guidelines for television organisations to direct the teleshopping market to the most advantageous areas. In Spain, studies continue to concentrate on the system’s main advantages and disadvantages, the target audience and levels of demand for this type of shopping. Studies in other countries (Grant, Guthrie and BallRokeach, 1991; Skumanich and Kintsfather, 1993, 1998) have extended the scope of research to analyse the possible links and relations the teleshopper has with this type of advertisements and/or programmes and their influence on the purchase, and the background or precursors to these relations. In Spain, very little research has been done up to now why this sales formula did not start until the early 1990s, the date when the first studies began to appear. The most relevant of these studies being both market studies on shopping habits in the new sales systems carried out by the Instituto Emer in several regions of Spain and the research done by De la Balli- [24] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping 06 599 na and González (1993), Sanz (2002), Sanz and Sánchez (2002a, 2002b) where this new sales formula is analysed in detail. Currently, there is a clear interest in studying interactive television and Interactive Home Shopping, as new, significant developments which are obviously driving or will drive in the not too distant future to the growth and importance of this type of non-store sales. However, there is a marked lack of interest in the traditional television sales formats. Interest in this field should be revived since these formats are at present the most commonly used and in the more immediate future, they will continue to complement the more innovative formats. This lack of interest and little research have encouraged us to study television sales in more detail. The objective of this work is to analyse, and thus highlight the growing relevance and importance of teleshopping, how the system has developed over time and its expectations for future development. 2. Teleshopping origins Sales through television channels began in Italy around 1980 then appeared in the United States and two years later were introduced in France. In the early stages, teleshopping services worked through an interactive system which allowed subscribers to send messages to their information providers who, in turn, were able to provide transactional services such as: placing standing orders, home banking and teleshopping (Marti and Zeilinger, 1982; McKay and Fletcher, 1988). The interactive facility stemmed from the fact that the shopper could not only receive general information on the sales organisation, but could also ask about available stocks, price, colour, size and even order a chosen item (Thompson, 1997). To make teleshopping available, the television set was connected to a minicomputer in the retail establishment by ordinary telephone lines. Consumers could order their products from the lists which appeared on the tv screen. At first, the information was only static and written, and so there were no images. september · december 2006 · esic market [25] 600 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping To place an order, the shopper pressed the appropriate buttons to introduce the item code number and the desired quantity. The consumer’s shopping list detailed item by item appeared on the screen with the corresponding account. The consumer could even recover old shopping lists because they were stored in the seller’s computer memory. Repeat orders could be quickly confirmed, items could be deleted and new items could be added before completing the transaction. When the order was finalised, it was recorded in the shop computer and was printed out in the form of a purchase order. The products were prepared by the staff in the shop for delivery to the consumer. In the majority of cases, delivery took place at the shop’s convenience, but in other cases, at the time requested by the shopper. Payment was in cash, by cheque or credit card as decided by the organisations participating in this new sales system. While teleshopping could appear an attractive proposal in some aspects, the system also had some limitations (see Table 1). Marti and Zeilinger (1982) paid special attention to the drawbacks of teleshopping, from the consumer’s point of view, and at that time the most serious disadvantages were: 1. The fact that the television was not available for watching programmes or the phone for making calls. 2. Possible risk of error if a mistake was made selecting the item codes. 3. The lack of a printed version to detect any possible errors. The first of the above problems was classified as minor, as these defects could easily be solved. Obviously the consumer would choose to shop by television when his favourite programmes were not on, or when there was no need to use the phone. The last two were more problematic. In any case, the majority of consumers were probably not dissuaded from teleshopping by just these setbacks. The above list of drawbacks was extended thanks to research by other authors such as McKay and Fletcher (1988), who after a study of consu- [26] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping 06 601 mer attitudes towards teleshopping concluded that most of those interviewed were opposed to the alternative of shopping by television on the basis of the following criticisms: 1. It meant a loss of social contact, emphasising the social function of traditional shopping. 2. It did not offer the visual stimulation of shopping in a shop. The physical aspects of the product, such as presentation and packaging were decisive when shopping and teleshopping was incapable of communicating this information through photographic presentations. The products, reduced simply to words and figures, lost aesthetic attraction and therefore the temptation to buy them. The lack of visual stimulation was a clear drawback to the teleshopping system. 3. Teleshopping was perceived as something not very interesting and lacking in mental stimulation. It was synonymous with lack of choice. It limited the number of products available, as all the items carried by a shop could not reasonably appear on the screen. Teleshopping therefore, did not offer as wide a range as the traditional shop. 4. It was not very suitable for buying perishable goods, clothes or footwear. These products are thought to need a priori examination before the purchase. 5. The benefits of home delivery also had negative aspects, such as the need to wait until the products were delivered, receive unwanted replacements, discover some items had run out and generally, receive products in poor condition. There was special emphasis on the need for an efficient customer service to reduce the inconvenience of having to return items. 6. The price of the products. The consumer did not consider that the purchases were competitive on price, since in addition to paying the price of the product, other costs also had to be paid, such as transport costs. september · december 2006 · esic market [27] 602 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping (1) It should be noted that several authors have worked on the concept of teleshopping, in the Table 1. Initial limitations of teleshopping early stages, as a very wide concept, including the purchase of items from the television or from the computer or telephone. Other authors extended the concept even further, including under teleshopping any other method of non store sales, i.e. any type of sales which could be made from the customer’s home, including catalogue or postal sales, which together with television were included in the term Direct Marketing. 1. Television not available to watch television programmes. 2. Telephone not available to make calls. 3. Risk of error when selecting item code numbers. 4. Lack of printed copy of the order to detect any errors. 5. Loss of social contact. 6. Lack of visual stimulation. 7. Lack of consumer interest in the service. 8. Limited number of products available. 9. System not appropriate for the sale of products such as: perishable goods, clothes and footwear. 10. Problems with the product delivery service. 11. Lack of efficient customer service. 12. Uncompetitive prices. Source: Adapted from Marti and Zeilinger (1982) and McKay and Fletcher (1988). There were therefore, several reasons which indicated the possible failure of teleshopping (seller’s operating costs, the range of products or legal barriers), with one of the clearest reasons being the lack of consumer interest. This, at first, caused doubts as to the future commercial feasibility of the teleshopping service1. In Spain, television sales started in the early 1990s on private channels. Teleshopping programmes were first broadcast with the launch of Antena 3 television. Through “La Teletienda Antena 3” this type of programme was introduced in a totally new way. These television sales slots were characterised, at first, by their serious nature, since presenters rarely appeared, it was mostly shots of the products announced with an off-camera voice commenting on them. There were also no testimonies or commenta- [28] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping 06 603 ries from the people who created the products or used them. These programmes were broadcast at different times: in the mornings from 11:00 to 12:00, in the afternoons at 15:30, 17:15, 18:30 and finally at 19:00 (Castelló, 2002). Until that moment, only those with a parabolic aerial had access to some teleshopping programmes. 3. Current situation of teleshopping In comparison with its beginnings, the concept of teleshopping has evolved considerably. Nowadays, some of the problems perceived by consumers to hinder the development and introduction of teleshopping appear to have been solved (visual stimulation, appropriate knowledge of the products, efficient customer service and competitive prices). There is no doubt that this commercial non-store sales formula has recently been experiencing significant developments both in Spain and other EU countries and has spectacular perspectives for growth. Teleshopping (teleshopping programmes or infomercials) can therefore be viewed as one of the most promising methods for the sale of goods and/or services, thanks especially to the new technologies that continue introducing new ways to access products and to purchase them from the television set. In addition, given that the television is extremely popular and is present in practically all households (CIS, 1997; EGM, 2005; El País, 1999; Núñez, 2000; MECD, 2002; SEDISI, 2000), sales through this medium are becoming an extraordinary force within commercial distribution (Díez de Castro, 1997; Gómez, 1995; Miquel, Parra, Lhermie and Miquel, 2006; Whitford, 1994). Therefore the phenomenon of teleshopping which started approximately twenty years ago, has very promising possibilities for development (Carcasona, 1994, Gómez, 1995), as indicated by the fact that, currently both private and state-run channels, including the regional and local channels, have slots dedicated to sales. Some foreign companies broadcast through Spanish channels and others in channels which can be seen with parabolic antennas, as for example Galavisión (teleshopping) or Sky Channel (Quantum Int. Ltd.), with well organised distribution logis- september · december 2006 · esic market [29] 604 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping tics in order to sell their products in Spain. Exclusive sales channels are even beginning to appear where it is possible to shop 24 hours a day (Ono’s teleshop EHS (European Home Shopping)). In addition to the above is the inclusion of sales in certain programmes, such as entertainment programmes, where the presenters present and sell the products (for example the sale of “Lo Monaco” mattresses in the programme “A tu Lado”). In these cases trust in the presenters generates greater credibility for the products and therefore increases sales. At present, three types of television sales are being developed most in Spain (see Table 2). Firstly, there are direct response advertisements, similar to conventional advertising but with a slightly longer duration (around two minutes), secondly the teleshop or video-catalogue programmes (which last about 15 minutes), and thirdly infomercials, long lasting sales programmes (up to 3 hours). Of these three, the most popular among the public are the video-catalogue programmes (Sanz, 2002), of which A3D, from Antena 3 TV was one of the most successful until its disappearance. It had more than 900,000 clients and consolidated as the leading Spanish company in the direct sales sector (A3D, 2003). In the year 2000 its turnover was 27.04 million euros using the channel’s least saturated advertising slots (Barrio and Nieto, 2003). Table 2. Types of teleshopping TYPES [30] CHARACTERISTICS Conventional direct response advertising • Short duration (between 60 and 120 seconds). • A single product is offered. • A telephone number is given to acquire the product Video-catalogue/teleshop programmes • • • • Minimum duration of 5 minutes. Maximum duration of 15 minutes. Several products are offered. A telephone number is given to acquire the product. september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping 06 605 Table 2. (Continuation) TYPES Long sales programmes (informercials or infocommercials) CHARACTERISTICS • Minimum duration between 15-20 minutes and half an hour (only one product is shown). • Maximum duration up to 3 hours (several products are advertised). • Broadcast in cheap and/or low audience time slots. • A telephone number is given to acquire the product. Source: Original work. These three forms of sales are included within the traditional teleshopping systems since, in all of them, the client requests the product by phone and it cannot be acquired any other way. Contact is made with the supplier of the goods or service and the sale is finalised by phone (Bragg, 1987; Díez de Castro, 1997; Gómez, 1995; Linke, 1992; Miquel et al., 2006; Quelch and Takeuchi, 1981). Nowadays in Spain, in comparison to other countries, telephone ordering is the most used system and is therefore still the current system. In addition to these traditional teleshopping systems, where the client makes a phone call to request a product/service, with the appearance and development of new technologies such as digital, satellite or cable TV (see Graph 1), the opportunity to shop directly (for programming or products/services) is being offered on non-sales channels which is thus leading to a complete rebuiliding of the television infrastructure (Grant, Guthrie and Ball-Rokeach, 1991). Thus, thanks to the development of interactive television, the consumer can purchase direct from the television set by simply pushing a button on the remote control, and charge the cost of the purchase to his credit card or bank account (Blake, 1996; Lee and Lee, 1995; Levy and Weitz, 1998; Linke, 1992). september · december 2006 · esic market [31] 606 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping Graph 1. The role of new technologies in sales Satellite Internacionalisation of slots Cable Consolidation of new chains Terrestrial • Programming specialisation • Adaptation to specific segments • Additional services: • • • • • Home banking Telephone Telework TELESALES Internet Access SALE BY TELEVISION Source: Original work. In addition, it should be mentioned that the consumer is beginning to have Internet access through the television set, which promotes yet further the development of television interactivity between the televiewer and the medium (Blake, 1996). Thus, the customer can view the catalogue of goods/services offered by different companies on his television screen, make his choice and buy the products after comparing ranges, conditions, prices and brands (Bliwas, 2000; Bramley, 2000; Caswell, 2000; Clawson, 1999; Frederiksen, 1997; Leonardi, 1999; Techtrends, 2000; Thompson, 1997; Yorgey, 1997). This new form of teleshopping (Internet), already available on the market for some companies, still has a very low level of introduction, and is therefore mentioned in this work as a future teleshopping formula, with perspectives for rapid growth on the Spanish market. [32] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping In other countries such as the United States and the United Kingdom, television is very highly developed and an example of this is the fact that interactive television and Internet by television have been available for some time, as have exclusive sales channels for products and/or services. Cable and satellite television are also good precursors for all these services, as they take advantage from their high number of televiewers to make significant sales through teleshopping2. These more innovative services are beginning to be developed now in Spain. In the United States, home shopping is a very powerful distribution channel, and there are more than 500 channels dedicated to this type of sales (Underwood, 1993; Whitford, 1994). The variety of products marketed is immense, with items from 12 euros to over 1,200 on sale (Ridsdale, 1993), with jewellery and cars being the most successful products (Whitford, 1994). On the North American market there are even independent Spanish language stations broadcasting sales programmes in Spanish, in order to reach a relatively wide audience such as the Hispanic market3 (Shermach, 1997). This market shows a predisposition or favourable attitude towards advertising and direct marketing, considering that both are important information sources (Korgaonkar, Karson and Lund, 2001). Nowadays, the telesales industry in the United States is worth over 2,000 million dollars (around 2,103 million euros). At present, one of the leading television channels in the teleshopping sector is QVC (Quality, Value, Convenience), which has been operating for over 15 years in the United States and, since a few years ago, in Canada, Mexico, Japan and Europe (France, the United Kingdom and Germany) as well (Stephens, Hill and Bergman, 1996). In 1992 this great teleshopping chain had a loyalty rating of around 60%. Out of every 10 viewers who made a purchase, 6 purchased again (Stephens, Hill and Bergman, 1996), this loyalty rating was maintained in 1997, together with the incorporation of 150,000 new clients every month (Thompson, 1997). Currently, it is present in more than 64 million households in the United States and around 6 million households in the United Kingdom (Leonardi, 1999). september · december 2006 · esic market 06 607 (2) An example of the huge potential and scope of this medium is the promotion of Frank Coffey’s book which in one of the sale programmes broadcast (QVC) in only 5 minutes sold 2,000 copies, with total sales of 8,000 copies over the total duration of the programme of just 17 minutes. (Whitford, 1994). (3) Currently, the Hispanic market has a population of around 25 million people with a spending capacity of around 150 billion dollars, justifying the importance of this market segment both for advertising and direct marketing (Korgaonkar, Karson and Lund, 2001). [33] 608 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping This leading sales chain achieved total sales of 1.6 billion dollars in 1995, with a 400 million dollar increase on the previous year (Underwood, 1996), and by the end of 1999 passed the 2.8 billion dollar mark (Sullivan, 2000). Although QVC was initially set up to market only cheap, low quality products (such as costume jewellery), nowadays, with the aim of increasing its target audience, it offers a wide variety of products through its different sales channels (for example the Q2 and On Q channels), some of which also specialise, among others, in family themed programmes, health, sports, fashion, fitness and travel (Rubel, 1995; Solomon, 1994; Thomphson, 1997; Underwood, 1996). Greater market segmentation and variety of products offered to its audiences (more than 200 products per hour) (Daugard, 1996) has meant that this company has recently begun to attract a more discerning public, in a higher income bracket offering better quality products at a consequently higher price (Miller and Zapolin, 1996; Underwood, 1996). The company uses a persuasive sales system in contrast to the aggressive sales system traditionally associated with telesales (Masko, 1997). QVC’s business was extended in the summer of 1996 by incorporating the service of shopping by PC (iQVC), offering its clients the opportunity to acquire products not only by television but also by Internet (Galenskas, 1997; Underwood, 1996). Another of the pioneering companies in teleshopping (founded in 1977) and also a market leader is HSN (Home Shopping Network). This company, in contrast with the previous one, attracts the middle income bracket consumer with lower price and lower perceived quality products (Miller and Zapolin, 1996). Sales at the end of 1999 were over 1.2 billion dollars (Sullivan, 2000). Like QVC, this leading chain has also extended its business with the Internet shopping service. This service started in 1995, a year before than its most direct competitor (QVC), and in even that first year obtained a turnover of 2 million dollars (Underwood, 1996). [34] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping Together with QVC and HSN, other teleshopping chains such as Value Vision (founded in 1990) and Shop at Home have also contributed to the success of this sales formula4 (Andersen, 1999; Underwood, 1996). Thanks to the development of these chains and in particular of the leading sales chains, i.e., QVC and HSN (present in over 140 million households (Mermigas, 2001)), teleshopping has a promising future (Eldridge, 1993). In fact, television sales have gone from 2.5 billion dollars in 1993 (Underwood, 1994) to 4 billion a year between the end of 1995 and 1996 (Miller and Zapolin, 1996; Underwood, 1996) and around 6 billion dollars at the end of 2000 and early 2001 (Mermigas, 2001). It is forecast that this figure will increase by 1.5 billion dollars over the next 4 years (Mermigas, 2001). 4. Implications of direct sales for companies All the indicators show that teleshopping will grow in the future. This will mean a change in consumers’ lives but also an important change for companies who hope to increase sales through the television medium, either by competing or doing business with it (Solomon, 1994). The growing tension between manufacturers and distributors is increasingly pushing manufacturers to search for alternative sales channels, which they often use in parallel with sales to large distributors, in order to decrease their dependency (Gómez, 1995). In fact, for manufacturers, the appearance and development of this form of sales means a further alternative (and in many cases a cheaper one) for making its products known and offering them to consumers without having to invest in costly conventional advertising campaigns to do so (Carcasona, 1994; Hawthorne, 1998b; Masko, 1997; Whitford, 1994). In addition, for the distributors, although this commercial formula means greater competition for them, they can take profit from it, using it to diversify their offer, as in the Spanish case of the El Corte Inglés5 (Gómez, 1995). Thus, sellers who add a telesales component to their shop or business can obtain a significant synergy (Barrett, 1996; Silverman, 1995; Solo- september · december 2006 · esic market 06 609 (4) Telesales for Value Vision and Shop at Home in the United States reached 218 million and 150 million dollars respectively in 1999 (Andersen, 1999). (5) This major distribution chain began broadcasting in June 2001 a series-type programme (Tele 5 in El Corte Inglés) made in the chain’s own stores, lasting about 20 minutes (from 10:00 to 10:20). In these programmes, some of the staff gave detailed presentations of several products which could be purchased at the stores or through the programme itself by phone. In total 4 or 5 products were advertised per programme, some were well known brands and prices, in most cases were over 30 euros. Along with the phone number to make the order, a guaranteed refund was offered, and the possibility of paying with any credit card, including the El Corte Inglés store card. This programme was broadcast every day from [35] 610 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping Monday to Friday as part of the daily scheduling and was even repeated in the early hours. (6) After the popularity of the El Corte Inglés products advertised by “Tele Tienda”, the major Spanish distribution chain decided to go into catalogue sales on its own without intermediaries. In late 1992 it set up an out of store sales department called “La Tienda en Casa”. Customers could place orders over the phone or using the coupon inside the catalogue. The launch of the first El Corte Inglés postal sales catalogue caused quite a stir among the companies already operating in the business, who were enjoying a particularly favourable period (Méndez, 1993). mon, 1994; Webster, 1997). For example, in the case where the consumer is not satisfied with the product purchased by television and providing this product is available in the shop, he can either return it or change it through the usual teleshopping channel or go to one of the advertiser’s sales outlets. As a result, the consumers may end up visiting the shop and buying more products there as well. Nowadays, the large companies in the distribution sector, such as Carrefour, have reached an agreement with teleshopping companies under which some of the products offered on the television (reducing ointments, gym apparatus, etc. ) are present throughout the chain. In the same way, television has also appeared as a support to postal sales (Dowling, 1997, Méndez, 1993). Currently, companies such as Spiegel and Time Warner, or El Corte Inglés6 in Spain, use telesales programmes to offer products from several of their sales catalogues, thus helping to promote the catalogue business. The telesshopping channel is used to generate orders by catalogue and simultaneously, the catalogue is used to promote the telesales channel. The products which appear in the catalogue with the note “sold on tv”, sell more (Dowling, 1997). Companies which do business using television sales need to realise that sales through this medium may be both a blessing and a nightmare. Television is able to sell thousands of products in a few minutes; this means that a small manufacturer needs to consider his production, stocks and warehousing before the product is broadcast on television, in order to meet whatever response there is to the advertisement. Replacing resources, reviewing strategies used in several departments, subcontracting part of the manufacturing process and not assigning so much capital to traditional advertisements are aspects which must be considered by the sellers/manufacturers who anticipate they could grow by selling through this medium (Solomon, 1994). In addition, this commercial formula will allow the manufacturers/ sellers themselves to control the results in the short term, as they can be observed and measured almost immediately (in a few hours, under a [36] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping week), so that the assumed risk is very controlled (Carcasona, 1994; Cotriss, 1998; Danaher and Green, 1997; Díez de Castro, 1997; Hawthorne, 1998a; Kaye, 1999; Masko, 1997; Whitford, 1994). Sellers who, initially, refuse to adopt telesales will have to develop new formats to make the experience of in-store shopping more stimulating and attractive, perhaps by providing entertainment, leisure activities or shows. They will also have to use new technologies to help consumers buy more easily and conveniently, such as for example introducing computer stations on sales floors so the consumers can find out about products, availability or future offers (Solomon, 1994). The professionalism and good practices of the different companies operating in the sector (product quality, delivery terms, guarantees, refunds, prices, etc.), European Union legislation7 on television-related issues, and the development and definitive introduction of interactive television are, among others, elements which will exert significant influence on the development of this type of sales. 06 611 (7) The legislation increases the time allowed for broadcasting conventional direct response advertisements, giving separate consideration to sales programmes and exclusive sales channels. 5. Perspectives of growth for teleshopping The most immediate future of teleshopping in Spain is without doubt, the development and definitive introduction of cable television and the digital communication networks. From these new technological advances, telesales will benefit given that: 1.- More time will be dedicated to sales slots (Gómez, 1995), so the different channels will broadcast more programmes of this type (Wicks, 1991). The sales or catalogue programmes on a cable channel are usually broadcast for around 30 minutes and can be shown to all the subscribers as part of the regular broadcasting schedule or only to individual subscribers on request and at their convenience. The availability of more broadcasting time will create, on the one hand, more competitive markets, as more viewing options will be available for the televiewer and on the other hand will lead to lower prices for september · december 2006 · esic market [37] 612 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping television slots (Gómez, 1995). This will doubtless favour the rapid growth of the traditional sales systems such as infomercials (long sales programmes for products and/or services) (Carcasona, 1994), and the development of new forms of catalogue programmes and commercial advertising (Díez de Castro, 1997). 2.- Specific channels will be dedicated to the sales of goods/services (Carcasona, 1994; Whitford, 1994; Wicks, 1991). This means that themed direct sales channels will appear from which to shop 24 hours a day. This formula will radically increase sales, as the consumer will be able to specifically choose a channel on the television at any time of day from which to teleshop and in addition, in the not too distant future, the service will be interactive (Blake, 1996; Thomphson, 1997; Whitford, 1994). Thus, the traditional system of phone shopping will survive alongside interactive shopping systems where the consumer can transmit the order through the television remote control (Blake, 1996). 3.- Internet access through the television set itself will be developed, which will mean a significant extension to the market (Frederiksen, 1997; TechTrends, 2000; Thomphson, 1997; Yorgey, 1997). In fact, most Internet and teleshoppers, together with subscribers to cable and satellite television are favourably disposed towards using this service (TechTrends, 2000). There will even be combinations of sales programmes and Internet, where the televiewers, by watching these programmes, will have direct access from the programme itself to the company website, simply by clicking on the web address which appears on the screen, which will allow consumers to see a product, select it and buy it using the remote control while watching the sales programme, without the need for a computer or a phone call. (Bramley, 2000; Caswell, 2000; Leonardi, 1999). In the United States, more than 80% of active teleshopping channel customers have already stated their interest in this service and therefore that they are ready to order and pay for the products through their television sets. Of these, 27% say they would pay a monthly fee for this service (TechTrends, [38] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping 06 613 2000). This combination of Internet and telesales will surely help to overcome some of the limitations inherent in the use of Internet alone (Chiles and McMackin, 1996; Frederiksen, 1997; Javenpaa et al., 1999; Lohce and Spiller, 1998; Pavitt, 1997; Swaminathan et al., 1999). In the United Kingdom, this interactive system has been available on the market (on the Sky Digital channel) since late 2000 and has been developed by NDS (leader in problem solving for companies using sophisticated interactive technologies), in collaboration with the sales channel QVC (Bramley, 2000). In the same way, this system has been developed by Worldgate Communications Inc., also in collaboration with the sales channel QVC, with the aim of introducing a new form of impulse buying in the sphere of e-commerce (Leonardi, 1999). It is predicted that in the short term, the television will be a direct response medium, with a significant change towards commercial advertising or programmes of the dot.com type, designed so it is possible to place orders straight away, request further information or visit the company’s websites (Bliwas, 2000; Card et al, 2000; Caswell, 2000; Clawson, 1999; Leonardi, 1999). In Spain, the first platform offering Internet services through the television was Quiero TV, with more than 80% of subscribers using this service (Gómez, 2001a). The offer ranged from several interactive television channels to services such as: e-mail accounts, mobile messaging, participation in forums, chats, food home delivery and shopping (books, music and electronics, insurance, bathroom fittings, etc.) (Marín and Marcelo, 2002). The concept Quiero Tv tried to transmit was that of participation, inviting all viewers to be an active part of the channels. However, currently, Quiero Tv no longer offers its services to the market, the main reason for its disappearance being its high risk business plans to compete with other pay-to-view channels. Outstanding, among others was the huge investment made both to capture customers and purchase contents which exceeded subscriber generated income by more than 100% (Noticias de Comunicación, 2002). september · december 2006 · esic market [39] 614 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping Internet-television convergence is becoming increasingly apparent (Carton, 2001; Dunphy, 2001; Kelling et al., 2000; Kenny y Marshall, 2000; Long, 2001; Robins, 2001; Serena, 2000), both in terms of technology and content (linn, 1999). However, despite the similitude between both media there are significant differences with respect to choice motivations and media use, giving rise therefore, to different benefits for each of them (Heeter, 2000; Kelling et al, 2000). In addition to the above, it is difficult to make these new services profitable and the television infrastructure itself is resistant to change, all motives which may mean that Internettelevision convergence is still some time away (Gómez, 2001b). 6. Barriers to the use of the teleshopping system Although everything seems to suggest that teleshopping will benefit from the development of cable and, digital communication networks, it should be noted that there are a series of barriers or obstacles to introducing product sales which may be a break on access and interest for companies. We refer to three main barriers: the cable operator, policies and costs. Firstly, it should be noted that cable operators, up to now, have not been very enthusiastic about commercial advertisements/programmes, since these operators have focussed mainly on obtaining income from subscribers rather than advertising, and are fairly sensitive to including it. Secondly, advertising programmes are not always considered positive, as they can lead the consumer to impulsive and/or compulsive buying of things which are really of no interest to him (Beatty and Ferrell, 1998; Christenson, Faber, De Zwaan, Raymond, Specker, Eckern, MacKenzie, Crosby and Mitchell, 1992; Cobb and Hoyer, 1986; Donthu and Gilliland, 1996; Faber, 1992; Faber, O’Guinn and Krych, 1987; O’Guinn and Faber, 1989; Ridsdale, 1993; Roberts, 1998; Rook, 1987; Rook and Fisher, 1995; Thomas and Quindry, 1999). Finally, the operators see commercial advertisements/programmes as a type of publicity and therefore, expect some type of compensation. Normally the operating station, in exchange for inserting an advertisement for free, [40] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping receives a percentage of the sales (usually 3-5%) generated by the orders transmitted by telephone or the interactive systems8. As with a conventional advertisement, it is also possible to buy an advertising slot to broadcast the advertisement/programme (Bragg, 1987; Cotriss, 1998; Daugard, 1996; Eicoff, 1995; Gómez, 1995; Mermigas, 2001; Quelch y Takeuchi, 1981; Ridsdale, 1993; Whitford, 1994). In the latter case, according to the duration of the telesales slot and the broadcasting time, the operator invoices the company which sells the products as though it were just another advertisement (Cotriss, 1998; Gómez, 1995). Low audience time slots are usually used to broadcast this type of programmes and this is therefore an important resource to mitigate the possible advertising crisis (Barrio and Nieto, 2003). Cable operators’ lack of interest, the negative view received by political agents and the costs generated by broadcasting the advertisements/programmes are some of the reasons why companies may abandon the idea of getting into the direct sales market through the television medium. 7. Conclusions Sales through the television medium is an interesting option for companies who want to expand their markets and diversify the offer of their products/services. This direct shopping formula, which appears as a complementary method to in-store sales, is currently undergoing significant development and is quite popular among consumers, boosting the importance of the television medium as a distribution and sales channel. The increase in the broadcasting of advertisements and/or sales programmes and the number of channels and companies which offer them, the appearance of exclusive, 24 hour a day shopping channels and the sale of products through certain programmes are, among others, aspects which show how important this shopping system is becoming. In addition, it must be noted that thanks to the liberalisation of telecommunications and the development of interactive television, the consumer is beginning to have access to a series of services hitherto unimagina- september · december 2006 · esic market 06 615 (8) This method of buying media in direct markets is known as “ Per order” (PO) or “Per-Inquiry” (PI) (Daugard, 1996; Eicoff, 1995). Some stations do not accept PI since, although the method guarantees a profit to the direct market, the medium may lose by receiving less money than if advertising had been paid for. In these cases the PI method gives way to the “cash library” where the station, before the direct market, benefits from the income, or the “guarantee purchase” method, where the direct market buys advertising space and the station guarantees a minimum number of orders (Eicoff, 1995). [41] 616 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping ble, including teleshopping. The development of interactivity will help the television to change from being a passive instrument to offering the televiewer the chance to participate in the content and therefore adopt a relatively active attitude to the television screen. Internet through television is an obvious example of the progress in this field and without doubt is one of the most interesting options for stimulating the use of this form of shopping. In less than 10 years time it is expected that the television will exceed the PC and most shopping transactions will take place through it, with a fully developed interactive television in both Europe and the United States (Barry, 2000; Cantwell, 2000; Card et al, 2000; Caswell, 2000; Lee and Lee, 1995; Strategis, 2000) By late 2000, interactive television was already present in almost 15 million households worldwide and for 2006, this figure is expected to reach over 240 million households. 8. References A3D (2003). Information about the company, in http://antena3directo.com ANDERSEN, A. (1999). “Nonstore retailing gains favour with consumer”. Chain Store Age, 75 (8), pp. 29a-32a. BARRETT, M. (1996). “Infomercial invasion”. Marketing, 4th April, pp. 21-23. BARRIO, J.; NIETO, G. (2003). La televisión y la televisión del futuro. Antena 3 television’s report. BARRY, D. (2000). “Report: Interactive TV to dominate European e-commerce”. In E-Commerce Times, 27th march, in http://www.ecommercetimes.com. BEATTY, S.E.; FERRELL, M.E. (1998). “Impulse buying: Modelling its precursors”. Journal of Retailing, 74 (2), pp. 169-191. BLAKE, K. (1996). “What’s wrong with infomercials?”. Consumers’ Research Magazine, 79(4), pp. 10-15. BLIWAS, R. (2000). “TV become direct response”. Advertising Age, 71(8), pp. 30-31. [42] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping 06 617 BRAGG, A. (1987). “TV’s shopping shows: Your next move?”. Sales and Marketing Management, 139 (5), pp. 84-89. BRAMLEY, D. (2000). “NDS: NDS delivers advanced interactive TV system for QVC the shopping channel”. MS Presswire, 16th february, pp. 1-2. CANTWELL, R. (2000). “Cable closes in on t-commerce dream”. Interactive Week, 7 (22), pp. 84-85. CARCASONA, A. (1994). “Cómo llevar a cabo una campaña de Televenta. Nuevos canales de distribución: la venta por televisión”. MK. Marketing y Ventas, 87 (december), pp. 40-42. CARD, D.; SINGER, C.; CASSAR, K.; LOIZIDES, L.: JOHNSON, M.; LEWIS, N.; YASSKIN, N.; PATEL, V. (2000). “Television. Interactive TV Projection”, Jupiter Research, 2 (15), in http://www.jup.com/home.jsp CARTON, K. (2001). “Internet and TV aren’t such strange bedfellows”. Electronic Media, 20 (32), pp. 9. CASTELLÓ, J. (2002): “El negocio de las teletiendas”, 20th december, in http://boletinbit.tv. CASWELL, S. (2000). “Digital TV: The future of e-commerce (Part IV)”. In E-Commerce Times, 23th march, in http://www.ecommercetimes.com CHILES, T. H.; MCMACKIN, J. F. (1996). “Integrating variable risk preferences, trust, and transaction cost economics”. Academy of Management Review, 21, pp. 73-99. CHRISTENSON, G.A.; FABER, R.J.; DEZWAAN, M.; RAYMOND, N.; SPECKER, S.; ECKERN, M.; MACKENZIE, T.B.; CROSBY, R.; MITCHELL, J. (1992). Compulsive buying: Descriptive characteristics and psychiatric comorbidity. Unpublished Manuscript, University of Minnesota. In Faber (1992). CIS (1997). En casa tenemos de todo. Estudios CIS nº 2218, july. Magazine 9. CLAWSON, T. (1999). “Thing you can do with a TV set (apart from watching tv)”. The Revolution TV Report, 16. Sponsored by NTL. COBB, C.J.; HOYER, W.D. (1986). “Planned versus impulse purchase behaviour”. Journal of Retailing, 62 (4), pp. 384-409. september · december 2006 · esic market [43] 618 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping COTRISS, D. (1998). “Is cable TV right for you?. Target Marketing, 21 (12), pp. 14. DANAHER, P.; GREEN, B.J. (1997). “A comparison of media factors that influence the effectiveness of direct response television advertising”. Journal of Interactive Marketing, 11 (2), pp. 46-58. DAUGARD, C. (1996). How to make big money on TV. Accessing the home shopping explosion behind the screens. United States of America: Upstart Publishing Company (a division of Dearborn Publishing group, Inc.) DE LA BALLINA, F.J.; GONZÁLEZ, F. (1993). “Los nuevos sistemas de venta: análisis de los programas de venta por televisión”. Revista Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa, 3 (2), pp. 103-116. DÍEZ DE CASTRO, E. (1997). Distribución Comercial (2ª edición). Madrid, Mc-Graw Hill. DONTHU, N.; GILLILAND, D. (1996). “Observations: The infomercial shopper”. Journal of Advertising Research, 36(2), pp. 69-76. DOWLING, M. (1997). “TV products star in catalogs”. Catalog Age, 14 (11), pp. 24-25. DUNPHY, L. (2001). “Companies help stations get on the Internet”, Electronic Media, 20 (1), pp. 36-37. EGM (2005): “Informe anual de la audiencia de televisión en el 2005”. Available in http://www.egm.es. EICOFF, A. (1995). Direct Marketing thought broadcast media: TV, radio, cable, infomercials, home shopping, and more. Chicago: NTC Business Books. EL PAÍS (1999). Anuario 1999. Equipamiento de los hogares españoles para el año 1998. ELDRIDGE, J.D. (1993). “Non-store retailing: Planning for a big future”. Chain Store Age, 69 (8), pp. 34A-36A. FABER, R.J. (1992). “Money change everything: Compulsive buying from a bio psychosocial perspective”. American Behavioural Scientist, 35(6), pp. 809-819. [44] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping 06 619 FABER, R.J; O’GUINN, T.C.; KRYCH, R. (1987). “Compulsive consumption”. En M. Wallendorf & P. Anderson (Eds), Advances in Consumer Research, pp. 132-135. Association for Consumer Research, Provo, UT. FOSTER, A. (1981). “Push-botton shopping-when will it happen?”. Retail and Distribution Management, (January-February), pp. 29-32. FREDERIKSEN, L. (1997). “Internet or infomercial: Which will turn your audience on?”. Marketing News, 31(2), pp. 15-16. GALENSKAS, S.M. (1997). “Interactive shopping on the Internet”. Direct Marketing, 60(4), pp. 50-51. GÓMEZ, E. (1995). “Televenta: distribución a través de la televisión”. Distribución y Consumo, 22 ( junio-julio), pp. 74-80. GÓMEZ, I. (2001a). “TV Interactiva en España (III): cable y digital terrestre pisando fuerte”, de 16th April, in http://www.baquia.com. – (2001b). “TV Interactiva en España”, MK Marketing y Ventas, 159 (junio), pp. 6-12. GRANT, A.E.; Guthrie, K.K.; Ball-Rokeach, S.J. (1991). “Television shopping: A Media System Dependency perspective”. Communication Research, 18 (6), pp. 773-798. HAWTHORNE, T.R. (1998a). “Opening doors to retail store”. Direct Marketing, 60 (9), pp. 48-51. – (1998b). “When & why to consider infomercials”. Target Marketing, 21(2), pp. 52-54. HEETER, C. (2000). “Interactivity in the context of designed experiences”. Journal of Interactive Advertising, 1 (1), in http://www.jiad.org. JAVENPAA, S.; TRACTINSKY, N.; SAARINEN, L.; VITALE, M. (1999). “Consumer trust in a Internet store: a cross cultural validation”, in http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol5/issue2/jarvenpaa.html. KAYE, T. (1999). “Got time on your hands?”. Television Broadcast, 22 (11), pp. 19-21. KELLING, K.; MCGOLDRICK, P.; FOWLER, D. (2000). “Social influences on the use of the television as a service and shopping delivery chan- september · december 2006 · esic market [45] 620 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping nels in the home: who holds the control?”. 29th EMAC Conference. 23-26 May, Rotterdam. KENNY, D.; MARSHALL, F. (2000). “Contextual Marketing the real business of the Internet”, Harvard Business Review, NovemberDecember, pp. 119-129. KORGAONKAR, P.; KARSON, E.; LUND, D. (2001). “Direct Marketing: A comparison of Hispanic and non-Hispanic perspectives”. International Journal of Advertising, 20 (1), pp. 25-47. LEE, B.; LEE, R.S. (1995). “How and why people watch TV: Implications for the future of interactive television”. Journal of Advertising Research, 35 (6), pp. 9-22. LEONARDI, K. (1999). “World gate and QVC link TV viewers to Internet shopping”. En revista E-Commerce Times, 25th January, in http://www.ecommercetimes.com. LEVY, M. R.; WEITZ, B.A. (1998). Retailing management (3rd ed.). Series in Marketing, Boston: Irwin/Mc Graw Hill. LINKE, E. (1992). “New home-shopping technologies”. Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, The OECD Observer, Paris 178 (October-November), pp. 17-20. LINN, C.A. (1999). “Online-service adoption likelihood”. Journal of Advertising Research, 39 (2), pp. 79-89. LOHCE, G.L.; SPILLER, P. (1998). “Electronic shopping”. Communications of the ACM, 41(7), pp. 81-97. LONG, C. (2001). “A look at ias through the TV screen”, Electronic News, 47 (4), pp.16-17. MARÍN, E.; MARCELO, J.F. (2002). “La televisión se vuelve interactiva: servicios de las nuevas plataformas digitales”. PC World, 183 (January), pp. 161-168. MARTI, J.; ZEILINGER, A. (1982). “Videotext in the high street”. Retail and Distribution Management, (September-October), pp. 21-26. MASKO, M. (1997). “What every brand manager needs to know about direct response television”. Brandweek, pp. 28-32. Supplement Infomercial 97 and Direct Response Television Sourcebook. [46] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping 06 621 MCKAY, J.; FLETCHER, K. (1988). “Consumers’ attitudes towards teleshopping”. The Quarterly Review of Marketing, 13 (3), pp. 1-7. MECD (Ministerio de Educación, Cultura y Deporte) (2002). Las cifras de la cultura en España. Estadísticas e indicadores. MÉNDEZ, C. (1993). “Televenta en España, ¿quién y cómo?”. Super Aral Linea, 2 (january), pp. 14-20. MERMIGAS, D. (2001). “Home shopping due for upgrade”. Electronic Media, 20 (6), pp. 23-25. MILLER, A.; ZAPOLIN, M. (1996). “Feeling at home on TV”. Boston Business Journal, 16(34), pp. 33-34. MIQUEL, S.; PARRA, F.; LHERMIE, C.; MIQUEL, M.J. (2006). (5ª ed.). Distribución Comercial. Madrid, Esic Editorial. NOTICIAS DE COMUNICACIÓN (2002). “ La TDT llegará a toda Europa antes de 2005”, de 4th juny, in http://www.liderdigital.com/noticias. NÚÑEZ, L. (2000). “Responsabilidad ética en el nuevo contexto de los medios audiovisuales”. La televisión como agente cultural, tomo I, pp. 1-14. UIMP, Valencia. O’Guinn, T.C.; Faber, R.J. (1989). “Compulsive buying: A phenomenological exploration”. Journal of Consumer Research, 16 (September), pp. 147-157. PAVITT, D. (1997). “Retailing and the super high street: the future of the electronic home shopping industry”. International Journal of Retail & Distribution Management, 25 (1), pp. 38-43. QUELCH, J.A.; TAKEUCHI, H. (1981). “No store Marketing: Fast track or slow?”. Harvard Business Review, 59 (4), pp. 75-84. RIDSDALE, P. (1993). “Enter QVC, but not as live as it hoped”. New Media Markets, 11(18), 23th September, pp. 5-6. ROBERTS, J.A. (1998). “Compulsive buying among college students: An investigation of its antecedents, consequences, and implications for public policy”. The Journal of Consumer Affairs, 32 (2), pp. 295-319. ROBINS, A. (2001). “Thinking outside the box”, Electronic News, 20 (15), pp.10. september · december 2006 · esic market [47] 622 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping ROGERS, E. M. (1982). Diffusion of innovations. New York: The Free Press. ROOK, D.W. (1987). “The buying impulse”. Journal of Consumer Research, 14 (September), pp. 189-199. ROOK, D.W.; FISHER, E.J. (1995). “Normative influences on impulsive buying behaviour”. Journal of Consumer Research, 22 (December), pp. 305-313. RUBEL, C. (1995). “Home shopping network targets young audience”. Marketing News, 29 (15), 17th july, pp. 13-15. SANZ, S. (2002). La venta por televisión. Propuesta de un modelo de relaciones con el medio televisivo. Unpublished Doctoral dissertation, University of Valencia. SANZ, S.; SÁNCHEZ, I. (2002a). “Perfil y motivos de compra del comprador televisivo español”. Best Papers Proceedings 2002. XVI Congreso Nacional y XII Congreso Hispano-Francés de la Asociación Europea de Dirección y Economía de la Empresa (AEDEM). Alicante. – (2002b). “Television Shopper Segmentation on Purchase Motives: The Spanish Teleshopper Case”, Multicultural Marketing Conference of the Academy Marketing Science, pp.811-826. Valencia. SEDISI (Asociación Española de Empresas de Tecnología de la Información) (2000). “Métrica de la sociedad de la información”, in http://www.internautas.org. SERENA, A. (2000). “Publicidad on-line o interactiva”, El publicista extra 2000, artículos de opinión sobre el futuro de la publicidad, pp. 142. SHERMACH, K. (1997). “Infomercials for Hispanics”. Marketing News, 31(6), pp. 1-2. SILVERMAN, G. (1995). “Planning and using infomercial campaigns effectively”. Direct Marketing, 58 (5), pp. 32-34. SKUMANICH, S.A.; KINTSFATHER, D.P. (1993). Television shopping: A mediated communications perspective. Paper presented at the annual conference of the Pennsylvania Sociological Society, Pittsburgh, PA. In Skumanich y Kintsfather (1998). [48] september · december 2006 · esic market development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping 06 623 – (1998). “Individual Media Dependency. Relations within television shopping programming: A causal model reviewed and revised”. Communication Research, 25 (2), pp. 200-219. SOLOMON, B. (1994). “TV shopping. Comes of age”. American Management Association, 83 (9), pp. 22-26. STEPHENS, D.L.; HILL, R.P.; BERGMAN, K. (1996). “Enhancing the consumer-product relationship: Lessons from the QVC home shopping Channel”. Journal of Business Research, 37 (3), pp. 193-200. STRATEGIS (2000). “El mercado interactivo de la TV sigue siendo complejo”, 23th October, in http://www.strategisgroup.com. SULLIVAN, S. (2000). “Shopping channels: Less of a hard sell”. Broadcasting & Cable, 130(49), pp. 86-90. SWAMINATHAN, V.; LEPKOWSKA-WHITE, E.; RAO, B. (1999). “Browsers or Buyers in Cyberspace?. An Investigation of Factors Influencing Electronic Exchange”, in http://www.ascusc.org/jcmc/vol5/issue2/ swaminathan.html TECHTRENDS (2000). “Los consumidores de EEUU se abren al comercio electrónico por televisión”, 28th December, in http://www.techtrends.com THOMAS, D.Q.; QUINDRY, J.C. (1999). “Exercise consumerism let the buyer beware”. Journal of Physical Education, Recreation & Dance, 68 (3), pp. 56-60. THOMPHSON, I. (1997). “New direct channels” In I. Thomphson (Eds), Home Shopping: The Revolution in Direct Sales, pp. 23-40. England: Financial Time and Media Decision. UNDERWOOD, E. (1993). “Why I’m a home shopper”. Brandweek, 19th April, pp. 22-26. – (1994). “Shopping hits home”. Mediaweek, 4 (34), pp. s26-s28. – (1996). “Is there a future for the TV mall?”. Brandweek, 37 (13), pp. 24-26. WEBSTER, N.C. (1997). “Marketers look to cable for direct-response ads”. Advertising Age, 68 (49), pp. S8-S10. WHITFORD, D. (1994). “TV or no TV”. Inc., 16 (6), pp. 63-67. september · december 2006 · esic market [49] 624 06 development of a sector with a bright future: teleshopping WICKS, J.L. (1991). “Varing commercialisation and clutter levels to enhance television airtime attractiveness in early fringe”. Journal of Media Economics, 4 (2), pp. 3-18. YORGEY, L.A. (1997). “Internet versus infomercial?. Target Marketing, 20 (7), pp. 20-22. [50] september · december 2006 · esic market