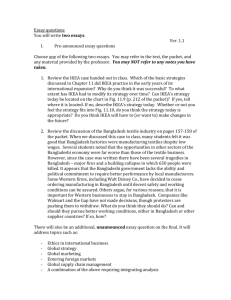

Corporate Social Responsibility at IKEA

advertisement