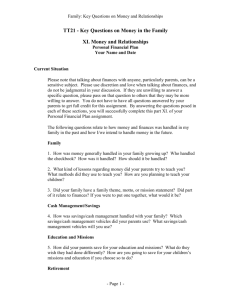

making financial decisions - The Money Carer Foundation

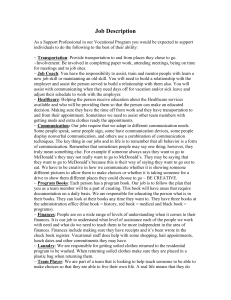

advertisement