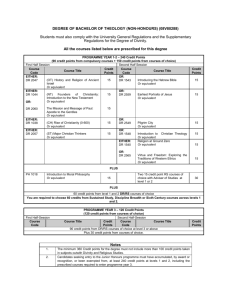

Annotated Glossary

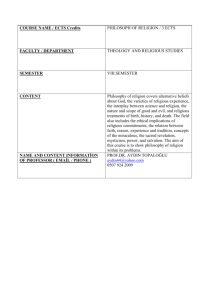

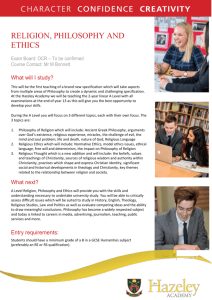

advertisement