PART ONE: First Things First: Beginnings in History, to 500 B

advertisement

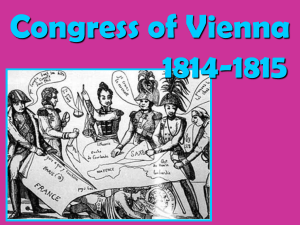

C HAP TER 22 Ideologies and Upheavals 1815–1850 CHAPTER LEARNING OBJECTIVES After reading and studying this chapter, students should be able to: • Explain how the victorious allies fashioned a general peace settlement, and how Metternich upheld a conservative European order. • Discuss the basic tenets of liberalism, nationalism, and socialism and identify groups most attracted by these ideologies. • Identify the major characteristics of the romantic movement, including some of the great romantic artists. • Analyze how liberal, national, and socialist forces challenged conservatism in Greece, Great Britain, and France after 1815. • Explain why revolutionaries triumphed briefly throughout most of Europe in 1848, only to fail almost completely. ANNOTATED CHAPTER OUTLINE The following annotated chapter outline will help you review the major topics covered in this chapter. I. 376 The Aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars A. The European Balance of Power 1. In 1814 the Quadruple Alliance of Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Great Britain finally defeated France and agreed to meet at the Congress of Vienna to fashion a general peace settlement. 2. The first Peace of Paris gave to France the boundaries it possessed in 1792, which were larger than those of 1789, and restored the Bourbon dynasty. 3. The Quadruple Alliance combined leniency toward France with strong defensive measures that included uniting the Low Countries under an expanded Dutch monarchy and increasing Prussian territory to act as a “sentinel on the Rhine.” 4. Klemens von Metternich and Robert Castlereagh, the foreign ministers of Austria and Great Britain, respectively, as well as their French counterpart, Charles Talleyrand, used a balance-of-power ideology to discourage aggression by any combination of states. 5. Napoleon undid this agreement briefly when he escaped from Elba and reignited his wars of expansion, but he was defeated at Waterloo in 1815. 6. The second Peace of Paris, concluded after Napoleon’s final defeat, was also C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS lenient with France, although this time France was required to pay an indemnity and to support an army of occupation for five years. 7. The Quadruple Alliance then agreed to meet periodically to discuss common interests and to guard the peace in Europe. 8. This European “congress system” lasted long into the nineteenth century and settled many international crises through international conferences and balance-ofpower diplomacy. B. Repressing the Revolutionary Spirit 1. Within their own countries, the leaders of the victorious states were much less flexible. 2. In a crusade against the ideas and politics of the dual revolution, the conservative leaders of Austria, Prussia, and Russia formed the Holy Alliance, which became a symbol of the repression of liberal and revolutionary movements all over Europe. 3. In 1820 revolutionaries succeeded in forcing the monarchs of Spain and the southern Italian kingdom of the Two Sicilies to grant liberal constitutions against their wills. 4. Metternich and Alexander I proclaimed the principle of active intervention to maintain all autocratic regimes. 5. Austrian forces then restored Ferdinand I to the throne of the Two Sicilies in 1821, while French armies in 1823 likewise restored the Spanish regime. 6. Metternich continued to battle against liberal political change, and until 1848 his system proved quite effective in central Europe, where his power was the greatest. 7. Metternich’s policies dominated the entire German Confederation, which comprised thirty-eight independent German states, including Prussia and Austria. 8. In 1819 Metternich had the German Confederation issue the infamous Carlsbad Decrees, which required the 377 thirty-eight German states to root out subversive ideas and which established a permanent committee to investigate and punish liberal or radical organizations. C. Metternich and Conservatism 1. Determined defender of the status quo, Prince Klemens von Metternich (1773– 1859) was an internationally oriented aristocrat who made a brilliant diplomatic career as Austria’s foreign minister from 1809 to 1848. 2. Metternich’s pessimistic view of human nature as prone to error, excess, and selfserving behavior led him to conclude that strong governments were necessary to protect society from the baser elements of human behavior. 3. Metternich defended his class and its rights and privileges with a clear conscience and at the same time blamed liberal middle-class revolutionaries for stirring up the lower classes. 4. Liberalism appeared doubly dangerous to Metternich because it generally went with national aspirations and a belief that each people, each national group, had a right to establish its own independent government and seek to fulfill its own destiny. 5. The multiethnic state Metternich served was both strong and weak—strong because of its large population and vast territories and weak because of its many and potentially dissatisfied nationalities that included Italians, Romanians, and various Slavic peoples, who were politically dominated by a German and Magyar (Hungarian) minority. 6. Metternich had to oppose liberalism and nationalism, for Austria was simply unable to accommodate these ideologies of the dual revolution. 7. In his efforts to hold back liberalism and nationalism Metternich was supported by the Russian Empire and, to a lesser extent, by the Ottoman Empire. 378 C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS 8. After 1815 both of these multinational absolutist states worked to preserve their respective traditional conservative orders. II. The Spread of Radical Ideas A. Liberalism and the Middle Class 1. In contrast to Metternich and conservatism, the new philosophies of liberalism, nationalism, and socialism started with an optimistic premise about human nature. 2. Liberalism—whose principal ideas were liberty and equality—demanded representative government as opposed to autocratic monarchy, and equality before the law as opposed to legally separate classes. 3. Opponents of liberalism criticized its economic principles, which called for unrestricted private enterprise and no government interference in the economy, a philosophy known as the doctrine of laissez faire. 4. In early nineteenth-century Britain this economic liberalism was embraced most enthusiastically by business groups and thus became a doctrine associated with business interests. 5. Labor unions were outlawed because they supposedly restricted free competition and the individual’s “right to work.” 6. As liberalism became increasingly identified with the middle class after 1815, some intellectuals and foes of conservatism felt that liberalism did not go nearly far enough. 7. These radicals called for universal voting rights, at least for males, and for democracy, and they were more willing than most liberals to endorse violent upheaval to achieve their goals. B. The Growing Appeal of Nationalism 1. Early advocates of nationalism were strongly influenced by Johann Gottfried von Herder, an eighteenth-century philosopher and historian who argued that 2. 3. 4. 5. 6. 7. 8. 9. each people had its own genius and its own cultural unity. In fact, in the early nineteenth century such cultural unity was more a dream than a reality, with an abundance of local dialects that kept peasants from nearby villages from understanding each other and historical memory that divided the inhabitants of various European states as much as it unified them. Despite these basic realities, sooner or later European nationalists usually sought to turn the cultural unity that they perceived into political reality. It was the political goal of making the territory of each people coincide with well-defined boundaries in an independent nation-state that made nationalism so explosive in central and eastern Europe after 1815. The rise of nationalism depended heavily on the development of complex industrial and urban society, which required much better communication between individuals and groups. Promoting the use of a standardized national language through mass education created at least a superficial cultural unity within many countries. Many scholars argue that nation-states emerged in the nineteenth century as “imagined communities” that sought to bind millions of strangers together around the abstract concept of an all-embracing national identity. Between 1815 and 1850 most people who believed in nationalism also believed in either liberalism or radical democratic republicanism. Liberals saw the people as the ultimate source of all government but agreed with nationalists that the benefits of selfgovernment would be possible only if the people were united by common traditions that transcended local interests and even class differences. C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS 10. Early nationalists usually believed that every nation, like every citizen, had the right to exist in freedom and to develop its character and spirit. 11. Yet early nationalism developed a strong sense of “we” and “they,” to which nationalists added two highly volatile ingredients: a sense of national mission and a sense of national superiority. C. French Utopian Socialism 1. Early French socialist thinkers saw the political revolution in France, the rise of laissez faire, and the emergence of modern industry as fomenting selfish individualism and splitting the community into isolated fragments. 2. They believed in economic planning and argued that the government should rationally organize the economy and not depend on destructive competition to do the job. 3. With an intense desire to help the poor, socialists preached economic equality among people and believed that private property should be strictly regulated by the government. 4. Count Henri de Saint-Simon (1760–1825) optimistically proclaimed that the key to progress was proper social organization in which leading scientists, engineers, and industrialists would carefully plan the economy and guide it forward by undertaking vast public works projects. 5. Charles Fourier (1772–1837) envisaged a socialist utopia of self-sufficient communities and advocated the total emancipation of women. 6. Louis Blanc (1811–1882) focused on practical improvements, and in his Organization of Work (1839) he urged workers to agitate for universal voting rights and to take control of the state peacefully. 7. In What Is Property? (1840) Pierre Joseph Proudhon (1809–1865) argued that property was profit that was stolen from 379 the worker, who was the source of all wealth. 8. The message of French utopian socialists interacted with the experiences of French urban workers, who became violently opposed to laissez-faire laws that denied workers the right to organize in guilds and unions. D. The Birth of Marxian Socialism 1. In 1848 Karl Marx (1818–1883) and Friedrich Engels (1820–1895) published The Communist Manifesto, which became the bible of socialism. 2. The atheistic young Marx had studied philosophy at the University of Berlin before turning to journalism and economics, and he had read extensively in French socialist thought before developing his own socialist ideas. 3. The interests of the middle class (the bourgeoisie) and those of the industrial working class (the proletariat) were inevitably opposed to each other, according to Marx. 4. Marx predicted that the ever-poorer proletariat, which was constantly growing in size and in class-consciousness, would conquer the bourgeoisie in a violent revolution. 5. Marx’s socialist ideas synthesized not only French utopian schemes but also English classical economics and German philosophy—the major intellectual currents of his day. 6. Marx’s theory of historical evolution was built on the philosophy of the German Georg Hegel (1770–1831), who believed that each age is characterized by a dominant set of ideas that produces opposing ideas and eventually a new synthesis. 7. Marx used this dialectic to explain the decline of agrarian feudalism and the rise of industrial capitalism while asserting that it was now the bourgeoisie’s turn to give way to the socialism of revolutionary workers. 380 C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS 8. Thus Marx pulled together powerful ideas and created one of the great secular religions out of the intellectual ferment of the early nineteenth century. III. The Romantic Movement A. Romanticism’s Tenets 1. The artistic change known as the romantic movement was in part a revolt against the emphasis on rationality, order, and restraint that characterized the Enlightenment and the controlled style of classicism. 2. Romanticism was characterized by a belief in emotional exuberance, unrestrained imagination, and spontaneity in both art and personal life. 3. Great individualists, the romantics believed the full development of one’s unique human potential to be the supreme purpose in life. 4. The romantics were enchanted by nature, and most saw modern industry as an ugly, brutal attack on their beloved nature and on the human personality. 5. In romanticism, the study of history was the key to a universe that was now perceived to be organic and dynamic, not mechanical and static as the Enlightenment thinkers had believed. 6. Historians such as Jules Michelet, who focused on the development of societies and human institutions, promoted the growth of national aspirations. B. Literature 1. Romanticism found its distinctive voice in a group of British poets led by William Wordsworth (1770–1850). 2. In 1798 Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772–1834) published their Lyrical Ballads, which was written in the language of ordinary speech and endowed simple subjects with the loftiest majesty. 3. Classicism remained strong in France until Germaine de Staël (1766–1817), in her study On Germany (1810), extolled the spontaneity and enthusiasm of German writers and thinkers. 4. Between 1820 and 1850, the romantic impulse broke through in the works of Lamartine, de Vigny, Dumas, George Sand, and Victor Hugo (1802–1885). 5. Hugo’s powerful novels, including Hunchback of Notre Dame (1831), exemplified the romantic fascination with fantastic characters, exotic historical settings, and human emotions. 6. Renouncing his early conservatism, Hugo equated freedom in literature with liberty in politics and society, a political evolution that was exactly the opposite of Wordsworth’s. 7. Amandine Aurore Lucie Dupin (1804– 1876), generally known by her pen name, George Sand, defied the narrow conventions of her time both by wearing men’s clothing and by writing on shockingly modern social themes. 8. In central and eastern Europe, literary romanticism and early nationalism often reinforced each other: The brothers Jacob and Wilhelm Grimm were particularly successful at rescuing German fairy tales from oblivion. 9. In the Slavic lands, romantics advanced the process of converting spoken peasant languages into modern written languages. 10. Aleksander Pushkin (1799–1837), the most influential of all Russian poets, used his lyric genius to mold the modern literary language. C. Art and Music 1. The great French romantic painter Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) was a master of dramatic, colorful scenes that stirred the emotions. 2. Notable romantic English painters included Joseph M. W. Turner (1775– 1851), who often depicted nature’s power and terror, and John Constable (1776– 1837), whose paintings depicted humans amid gentle Wordsworthian landscapes. C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS 3. Abandoning well-defined structures, the great romantic composers used a wide range of forms to create a thousand musical landscapes and evoke a host of powerful emotions. 4. The crashing chords evoking the surge of the masses in Chopin’s Revolutionary Etude and the bottomless despair of the funeral march in Beethoven’s Third Symphony plumbed the depths of human feeling. 5. Music became a sublime end in itself, expressing the endless yearning of the soul, and made cultural heroes of composers and musicians who evoked great emotional responses. 6. The most famous romantic composer, Ludwig van Beethoven (1770–1827), used contrasting themes and tones to produce dramatic conflict and inspiring resolutions. 7. Even though Beethoven began to lose his hearing at the peak of his fame and eventually became completely deaf, he continued to compose immortal music throughout his life. IV. Reforms and Revolutions Before 1848 A. National Liberation in Greece 1. Despite living under the domination of the Ottoman Turks since the fifteenth century, the Greeks had survived as a people, united by their language and the Greek Orthodox religion. 2. The rising nationalism of the nineteenth century led to the formation of secret societies and then to revolt in 1821, led by Alexander Ypsilanti, a Greek patriot and a general in the Russian army. 3. At first, the Great Powers were opposed to all revolution and refused to back Ypsilanti. 4. Yet many Europeans responded enthusiastically to the Greek national struggle, and as the Greeks battled on against the Turks they hoped for the support of European governments. 381 5. In 1827 Great Britain, France, and Russia yielded to popular demands at home and directed Turkey to accept an armistice. 6. When the Turks refused, the navies of these three powers trapped the Turkish fleet at Navarino and destroyed it. 7. Great Britain, France, and Russia finally declared Greece independent in 1830 and installed a German prince as king of the new country in 1832. B. Liberal Reform in Great Britain 1. Eighteenth-century British society had been both flexible and remarkably stable. 2. The common people had more than the usual opportunities of the preindustrial world, while basic civil rights for all were balanced by a tradition of deference to one’s social superiors. 3. Conflicts between the ruling class and laborers were sparked in 1815 when the landed aristocracy selfishly forced changes in the Corn Laws, with the result being that the importation of foreign grain was prohibited unless the price at home rose to improbable levels. 4. The revision of the Corn Laws during a time of widespread unemployment and postwar economic distress triggered protests and demonstrations by urban laborers. 5. The Tory government, completed controlled by the landed aristocracy, responded by temporarily suspending the traditional rights of peaceable assembly and habeas corpus. 6. Two years later, Parliament passed the infamous Six Acts, which placed controls on a heavily taxed press and practically eliminated all mass meetings. 7. In the 1820s, a less frightened Tory government moved in the direction of better urban administration, greater economic liberalism, civil equality for Catholics, and limited importation of foreign grain. 382 C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS 8. These actions encouraged the middle classes to press on for reform of Parliament so they could have a larger say in government. 9. The Whig Party had by tradition been more responsive to middle-class commercial and manufacturing interests and sponsored the Reform Bill of 1832. 10. A surge of popular support propelled the bill into law and moved politics in a democratic direction that allowed the House of Commons to emerge as the allimportant legislative body. 11. The new industrial areas of the country gained representation in the Commons, “rotten boroughs” were eliminated, and the number of voters increased by 50 percent to about 12 percent of adult men; thus a major reform had been achieved peacefully. 12. The principal radical program for continued reform was embodied in the “People’s Charter” of 1838 and the Chartist movement, which demanded universal male (but not female) suffrage. 13. In addition to calling for universal male suffrage, many working-class people joined with middle-class manufacturers in the Anti–Corn Law League, founded in Manchester in 1839. 14. When Ireland’s potato crop failed in 1845 and famine prices for food seemed likely in England, a handful of Tories joined with the Whigs to repeal the Corn Laws in 1846 and allow free imports of grain. 15. From that point on, the liberal doctrine of free trade became almost sacred dogma in Great Britain. 16. The Tories passed the Ten Hours Act of 1847, which limited the workday for women and young people in factories to ten hours, and they continued to champion legislation regulating factory conditions. 17. This healthy competition between a stillvigorous aristocracy and a strong middle class to gain the support of the working class was a crucial factor in Great Britain’s peaceful evolution. C. Ireland and the Great Famine 1. The people of Ireland, most of whom were Irish Catholics, did not benefit from the political competition in Britain but remained under the oppression of a tiny minority of Church of England Protestant landlords. 2. The condition of the Irish peasantry around 1800 was abominable, described by novelist Sir Walter Scott as “the extreme verge of human misery.” 3. Despite the terrible conditions, the population of Ireland continued to grow, from 3 million in 1725 to 8 million by 1840, a population explosion that was caused primarily by the extensive cultivation of the potato. 4. The decision to marry and have large families made sense for peasants: rural poverty was inescapable and better shared with a spouse, while a dutiful son or a loving daughter was an old person’s best hope of escaping destitution. 5. As population and potato dependency grew, conditions became more precarious, and potato crop failures in 1845, 1846, 1848, and 1851 resulted in the Great Famine, a period of widespread starvation and mass fever epidemics. 6. The British government was slow to act, and when it did, its relief efforts were tragically inadequate. 7. Moreover, the government continued to collect taxes, landlords demanded their rents, and tenants who could not pay were evicted. 8. The Great Famine shattered the pattern of Irish population growth: fully 1 million emigrants fled the famine between 1845 and 1851, and at least 1.5 million died or went unborn because of the disaster. 9. The Great Famine also intensified antiBritish feeling and promoted Irish nationalism, eventually leading to campaigns for Irish independence. C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS D. The Revolution of 1830 in France 1. Louis XVIII’s Constitutional Charter of 1814 was a basically liberal constitution that fully protected the economic and social gains of the middle class and the peasantry in the French Revolution, permitted great intellectual and artistic freedom, and created a parliament with upper and lower houses. 2. Louis XVIII’s charter was anything but democratic, however, allowing only about 100,000 of the wealthiest males out of a total population of 30 million to vote. 3. Nevertheless, the “notable people” who did vote came from a variety of backgrounds and included wealthy businessmen, war profiteers, successful professionals, ex-revolutionaries, and large landowners from the middle class and the old aristocracy. 4. Louis’s successor, Charles X (r. 1824– 1830), wanted to re-establish the old order in France but was blocked by the opposition of the deputies, so in 1830 he turned to military adventure in an effort to rally French nationalism and gain popular support. 5. In June 1830, in response to a longstanding dispute with Muslim Algeria, a French force of 37,000 crossed the Mediterranean and took the Algerian capital city of Algiers in three short weeks. 6. In 1831 tribes in the interior revolted and waged a fearsome war until 1847, when French armies finally subdued the country and expropriated large tracts of Muslim land. 7. Emboldened by the good news from Algeria, Charles repudiated the Constitutional Charter in July 1830, stripped much of the middle class of its voting rights, and censored the press. 8. After “three glorious days” of insurrection in the capital, the government collapsed, and Charles fled. 383 9. Then the upper middle class, which had fomented the revolt, seated Charles’s cousin, Louis Philippe, duke of Orléans, on the vacant throne. 10. Louis Philippe (r. 1830–1848) accepted the Constitutional Charter of 1814 and admitted that he was merely the “king of the French people.” 11. The situation in France remained fundamentally unchanged, however— there had been only a change in dynasty to protect the status quo for the upper middle class—and social reformers and the poor of Paris were bitterly disappointed. V. The Revolutions of 1848 A. A Democratic Republic in France 1. The political and social response to the economic crisis of the 1840s was unrest and protest, with “prerevolutionary” outbreaks all across Europe. 2. By the late 1840s, revolution in Europe was almost universally expected, but it took revolution in Paris—once again—to turn expectations into realities. 3. For eighteen years Louis Philippe’s “bourgeois monarchy” had been characterized by a glaring lack of social legislation and by politics dominated by corruption and selfish special interests. 4. The government’s stubborn refusal to consider electoral reform eventually touched off a popular revolt in Paris on February 22, 1848, when rebellious workers and students, armed with guns and dug in behind barricades, demanded a new government. 5. When Louis Philippe refused to order a full-scale attack by the regular army, the revolutionaries proclaimed a provisional republic, headed by a ten-man executive committee, and immediately drafted a constitution for France’s Second Republic. 6. They wanted a truly democratic republic and so gave the right to vote to every adult male while also freeing all slaves in French colonies, abolishing the death 384 C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS 7. 8. 9. 10. 11. 12. 13. 14. 15. penalty, and establishing a ten-hour workday in Paris. Profound differences within the revolutionary coalition in Paris reached a head in 1848 in the face of worsening depression and rising unemployment. Moderate liberal republicans, having conceded to popular forces on the issue of universal male suffrage, were willing to provide only temporary relief and were opposed to any further radical social measures. On the other hand, radical republicans and artisans hated the unrestrained competition of cutthroat capitalism and advocated a combination of strong craft unions and worker-owned businesses. The resulting compromise set up national workshops, which were soon to become little more than a vast program of pickand-shovel public works that satisfied no one. As the economic crisis worsened, the number enrolled in the workshops soared from 10,000 in March to 120,000 by June, with another 80,000 trying unsuccessfully to join. Alexis de Tocqueville (1805–1859), one of the newly elected members of the Constituent Assembly, observed that the socialist movement in Paris aroused the fierce hostility of France’s peasants, who owned land, and of the middle and upper classes. The clash of ideologies—of liberal capitalism and socialism—became a clash of classes and arms after the elections. Fearing that their socialist hopes were about to be dashed, artisans and unskilled workers invaded the Constituent Assembly on May 15 and tried to proclaim a new revolutionary state. As the workshops continued to fill and grow more radical, the fearful but powerful propertied classes in the Assembly dissolved the national workshops in Paris, giving the workers the choice of joining the army or going to workshops in the provinces. 16. The result was a spontaneous and violent uprising; barricades sprang up again in the narrow streets of Paris, and a terrible class war began. 17. After three terrible “June Days” of street fighting and the death or injury of more than ten thousand people, the republican army under General Louis Cavaignac stood triumphant in a sea of working-class blood and hatred. 18. In place of a generous democratic republic, the Constituent Assembly completed a constitution featuring a strong executive. 19. Louis Napoleon, nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte, won the election of December 1848, fulfilling the desire of the propertied classes for order at any cost and producing a semi-authoritarian regime. B. The Austrian Empire in 1848 1. The revolution in the Austrian Empire began in Hungary in 1848, where nationalistic Hungarians demanded national autonomy, full civil liberties, and universal suffrage. 2. When the monarchy in Vienna hesitated, Viennese students and workers took to the streets, while peasant disorders broke out in parts of the empire. 3. The Habsburg emperor Ferdinand I (r. 1835–1848) capitulated and promised reforms and a liberal constitution, while Metternich fled in disguise toward London. 4. The coalition of revolutionaries was not stable, however, and once the monarchy abolished serfdom, the newly free peasants lost interest in the political and social questions agitating the cities. 5. Meanwhile, the coalition of urban revolutionaries broke down along class lines over the issue of socialist workshops and universal voting rights for men. C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS 6. In March the Hungarian revolutionary leaders pushed through an extremely liberal, almost democratic, constitution, but they also sought to transform Hungary’s multitude of peoples into a unified and centralized Hungarian nation. 7. To the minority groups that formed half of the population—the Croats, Serbs, and Romanians—unification was unacceptable, as each group felt entitled to political autonomy and cultural independence. 8. Finally, the conservative aristocratic forces regained their nerve under the rallying call of the archduchess Sophia, Ferdinand’s sister-in-law, who insisted that Ferdinand abdicate in favor of her son, Francis Joseph. 9. On June 17, the army bombarded Prague and savagely crushed a working-class revolt. 10. At the end of October, the regular Austrian army attacked the student and working-class radicals barricaded in Vienna and retook the city at the cost of more than four thousand casualties. 11. After Francis Joseph (r. 1848–1916) was crowned emperor of Austria, Nicholas I of Russia (r. 1825–1855) sent 130,000 Russian troops into Hungary on June 6, 1849, and they subdued the country after bitter fighting. 12. For a number of years, the Habsburgs ruled Hungary as a conquered territory. C. Prussia and the Frankfurt Assembly 1. When the artisans and factory workers in Berlin joined temporarily with middleclass liberals in March 1848 in the struggle against the Prussian monarchy, the autocratic yet compassionate Frederick William IV (r. 1840–1861) vacillated and finally caved in. 2. On March 21, he promised to grant Prussia a liberal constitution and to merge Prussia into a new national German state. 385 3. When the workers issued a series of democratic and vaguely socialist demands that troubled their middle-class allies, a conservative clique gathered around the king to urge counter-revolution. 4. In May, a National Assembly convened in Frankfurt to write a German federal constitution, but the members of the Assembly were distracted by Denmark’s claims on the provinces of Schleswig and Holstein, which were inhabited primarily by Germans. 5. The National Assembly called on the Prussian army to respond, and Prussia subsequently began war with Denmark. 6. In March 1849, the National Assembly finally completed its drafting of a liberal constitution and elected King Frederick William of Prussia emperor of the new German national state. 7. Frederick William reasserted his royal authority, disbanded the Prussian Constituent Assembly, and granted his subjects a limited, essentially conservative constitution. 8. When Frederick William, who really wanted to be emperor but only on his own authoritarian terms, tried to get the small monarchs of Germany to elect him emperor, Austria balked. 9. Supported by Russia, Austria forced Prussia to renounce all its schemes of unification in late 1850, and the German Confederation was re-established. 10. Attempts to unite the Germans—first in a liberal national state and then in a conservative Prussian empire—had failed completely. CHAPTER QUESTIONS Following are answer guidelines for the Review Questions that appear in the textbook chapter, and answer guidelines for the chapter’s Map Activity, Visual Activity, Individuals in Society, Listening to the Past, and Living in the Past questions located in the Online Study Guide at bedfordstmartins.com/ 386 C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS mckaywest. For your convenience, the questions and answer guidelines are also available in the Computerized Test Bank. Review Questions 1. How did the victorious allies fashion a general peace settlement, and how did Metternich uphold a conservative European order? (p. 686) • In 1814 the victorious allied powers sought to restore peace and stability in Europe. The Quadruple Alliance—Russia, Prussia, Austria, and Great Britain—dealt moderately with France by giving it the boundaries it had possessed in 1792 and by not assigning any war reparations. The peace settlement also included strong defensive measures, resolved the various disputes among the Great Powers, and laid the foundations for beneficial international cooperation throughout much of the nineteenth century. Led by Metternich, the conservative powers used intervention and repression as they sought to prevent the spread of subversive ideas and radical changes in domestic politics. The formation of the Holy Alliance was the first step in this crusade against the ideas and politics of the dual revolution. 2. What were the basic tenets of liberalism, nationalism, and socialism, and what groups were most attracted to these ideologies? (p. 691) • After 1815 the ideologies of liberalism, nationalism, and socialism all developed to challenge the existing order in this period of early industrialization and rapid population growth. The principal ideas of the liberalism movement were equality and liberty, which were expressed in representative government, civil rights, and limited government regulation of the economy. Nationalism was based on the notion that each people had its own genius and cultural unity; to this was then added the idea that each people also deserved its own political entity and its own government. The key ideas of socialism were economic planning, greater economic equality, and the state regulation of property. All of these basic tenets in one way or another rejected conservatism, with its stress on tradition, hereditary monarchy and aristocracy, and an official church. Business groups and the middle class were attracted to liberalism; liberals and democrats were attracted to nationalism, and workers and utopian theorists were drawn to socialism. 3. What were the characteristics of the romantic movement, and who were some of the great romantic artists? (p. 697) • The romantic movement, breaking decisively with the dictates of classicism, reinforced the spirit of change and revolutionary anticipation. The romantic movement was characterized by a belief in self-expression, imagination, and spontaneity in art as well as in personal life. Among the most notable poets and writers Wordsworth, Hugo, and Pushkin stand out. So do two brilliant Frenchwomen, Germaine de Staël and Amadine Dupin, known by her pen name of George Sand. Famous romantic artists included Turner with his turbulent seascapes, Constable with his peaceful English countryside, and Delacroix with his exotic scenes. In music romantic composers, led by Beethoven, Liszt, and Chopin, plumbed the depths of human emotions and virtuoso performers became cultural heroes. 4. How after 1815 did liberal, national, and socialist forces challenge conservatism in Greece, Great Britain, and France? (p. 701) • Inspired by modern nationalism, Greek patriots rebelled against their Turkish rulers, and with the help of the European powers they won their national independence after a long struggle. In Great Britain the liberal challenge to the conservative order eventually led to fundamental reforms, as high tariffs on imported grain were reduced and then abolished, more men gained the right to vote with the Reform Act of 1832, and the factory workday for women and children was reduced to ten hours in 1847. In France, a three-day revolution in 1832 replaced the reactionary Charles X with the more moderate Louis Philippe, but little else changed. 5. Why in 1848 did revolution triumph briefly throughout most of Europe, and why did it fail almost completely? (p. 707) • In 1848 the increasing pressures of bad harvests, unemployment, rapid population growth, and a severe economic crisis exploded dramatically across Europe as they culminated in liberal and nationalistic revolutions. Monarchies panicked and crumbled in the face of popular uprisings and widespread opposition that cut across class lines, and the revolutionaries triumphed, first in France and then all across the continent. Yet very few revolutionary goals were realized. The moderate, nationalistic middle classes were unable to C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS consolidate their initial victories. Instead, they drew back when artisans, factory workers, and radical socialists rose up to present their own much more revolutionary demands. This retreat facilitated the efforts of dedicated aristocrats in central Europe to reassert their power. And it made possible the crushing of Parisian workers by a coalition of solid bourgeoisie and landowning peasantry in France. Thus the lofty ideals of a generation drowned in a sea of blood and disillusion. Map Activity Map 22.1: Europe in 1815 Analyzing the Map: Trace the political boundaries of each Great Power, and compare their geographical strengths and weaknesses. What territories did Prussia and Austria gain as a result of the war with Napoleon? • Russia: The Russian Empire extended from what was once the Kingdom of Poland in the west across all of northern Asia to the east. In the north Russia is bound by Finland and the Baltic Sea and in the south by the Black Sea. The empire’s northern and southern borders gave it access to important ports, like Riga and St. Petersburg. Not all of the borders were easily defensible natural borders, as with the part of Poland on the west of the Vistula River, which could be vulnerable to attack. • Prussia: Prussia was still centered on the city of Berlin, but had gained control over Saxony. It also had control over the region around Cologne, which bordered France. Prussia’s northern border was the Baltic Sea. To the south, Bohemia formed the border with the Austrians. This region was a strong emerging industrial state, but its borders were discontinuous. The Prussians also had access to the important port city of Danzig. Potential weaknesses for the Prussians were their Austrian and Russian borders, since there were no natural surroundings like rivers or oceans to help them defend these borders. • Austria: The Austrian Empire extended from Milan in the west, Galicia in the east, Bohemia in the north, to Hungary and Croatia in the south. This gave the Austrians major trading cities, like Venice, Prague, and Budapest, which generated wealth for the empire. The diverse populations over which the Austrians ruled were a constant problem for the 387 ruling Habsburg dynasty. The Hungarians, in particular, were a frequent source of civil unrest. • Great Britain: Great Britain was made up of the separate kingdoms of England, Scotland, Wales, and Ireland. As Great Britain consisted of two large islands, it shared no borders with the other Great Powers. This made it easier for them to defend their borders, and England based their military powers on their superior navy. They were, however, the smallest of the Great Powers and could not raise armies as large as those of the continental powers. • France: France was bordered by the Netherlands and Prussia in the north, Switzerland and Italy to the east, Spain to the south, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west. They also ruled the island of Corsica. These borders gave France access to both Atlantic and Mediterranean ports, which was beneficial for their world trade. They did not share borders with some of their traditional enemies, the Austrians and Russians; buffer states separated them from those powers. The disadvantage was that the Great Powers agreed to support those buffer states to prevent France from starting any wars. France was surrounded by states determined to keep them from expanding again. Connections: How did Prussia’s and Austria’s territorial gains contribute to the balance of power established at the Congress of Vienna? What other factors enabled the Great Powers to achieve such a long-lasting peace? • Balance of power: The Congress of Vienna created a ring of strong states around France, which reduced France’s power on the continent. France was not destroyed, however, for fear of making other powers too strong. The congress also created two strong powers in Central Europe, Prussia and Austria, who served to balance France’s power as well as each other’s. Russia remained a strong Eastern European power to check the strength of Austria and Prussia. • Long-lasting peace: Aside from creating strong European states, the Congress of Vienna created a settlement to the Napoleonic Wars that would guarantee many years of peace. The Great Powers agreed to periodic meetings to resolve future conflicts. They all agreed that revolutions had to be prevented at all costs, and agreed to suppress liberals and nationalists in their countries. They also promised not to give support to revolutionary movements in their rival’s territories. 388 C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS Visual Activity The Triumph of Democratic Republics Analyzing the Image: How many different flags can you count and/or identify? How would you characterize the types of people marching and the mood of the crowd? • Flags: There are a number of different flags in the crowd, but the most visible ones are the flags of France (red, white, blue), Germany (black, red, yellow), Italy (green, white, red), and Greece (blue and white). Further in the background, there appear to be four or five more flags, though they are too distant to determine which countries they might represent. • Mood: The mood of the crowd seems upbeat and happy. People are hugging each other, some are dancing, and others are raising their hats in celebration. Connections: What do the angels, Statue of Liberty, and discarded crowns suggest about the artist’s view of the events of 1848? Do you think this illustration was created before or after the collapse of the revolution in France? Why? • Symbolic images: The angels suggest a blessing has ensured the success of the revolutions, and the Statue of Liberty promises that equality will now rule. The discarded crowns clearly indicate that the monarchy is no longer needed. All three symbols strongly suggest that the artist viewed the early events of 1848 as a success for liberty and a blow to tyranny. • Before the collapse: It seems clear that the image was painted before the collapse of the revolution in France. The image is full of triumphant celebration over the deaths of monarchies and the success of republican equality. The painting would probably not be as joyous if it were painted after the revolution collapsed. abandon traditional rules and classical models in art and life. She believed that enthusiasm was the necessary ingredient in expressing creativity and reaching personal fulfillment. • Emotional intensity: Lives of famous Romantics were lived with great emotional intensity; suicide, duels, madness, and strange illnesses were not uncommon. Similarly, Staël’s life was one of emotional extremes; she suffered a mental breakdown at a young age, spent much of her adult life taking lovers, experimenting with opium, and attending great parties full of European intellectuals, and carried with her a sustained sense of melancholy, inspired by exile and disappointments in love, which characterized much of her written work. 2. Why did male critics often attack Staël? What did these criticisms tell us about gender relations in the early nineteenth century? • Gender in the early nineteenth century: In the early nineteenth century, writing was generally considered a male activity. Some of Staël’s critics were likely worried that her talent challenged the notion that women did not belong in a man’s world of serious thought and action, and created more serious competition for them. Even Staël’s supporters believed that her talent as a writer was simply an unusual accident. Staël’s experience shows that the early nineteenth century was still a world in which male chauvinism ruled. Listening to the Past Von Herder and Mazzini on the Development of Nationalism 1. How, according to Herder, did European nationalities evolve to create “the common spirit of Europe”? 1. In what ways did Germaine de Staël’s life and thought reflect basic elements of the romantic movement? • Intermingling: Herder believes that a key part of the development of “the common spirit of Europe” was the multitude of peoples and tribes who intermingled. Without such cultural blending, this common spirit could never have been awakened. • Christianity: Herder also believes that Christianity was key in creating this common spirit. He states that the introduction of Christianity unified Europe in a way that the Roman Empire could never do through force. • Emphasis on emotion: Much like the unconstrained Romantics, Staël urged people to 2. Why, according to Mazzini, should Italian workers support Italian unification? Individuals in Society Germaine de Staël C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS • Self-interest: Mazzini implores Italian workers to support Italian unification on behalf of their own self-interest. In order to change their unjust social conditions, Italian workers must appeal to a common consensus. Mazzini argues, however, that no consensus can exist unless a nation consisting of people similar in language, tendency, and tradition also exists. Otherwise, the worker’s pleas for reform will fall on deaf ears. 3. How are Herder and Mazzini’s views similar? How do they differ? • Similar: Both Herder and Mazzini believed that language determined nationality, and that each people had its own particular genius and traditions that should be preserved. • Different: Herder appealed to a common bond and ancestry among all peoples in Europe. While he advocated that unique traditions be preserved, he did not support the creation of political entities or nationstates. Mazzini, on the other hand, argues that the formation of nation-states is the most effective way to preserve these traditions. Living in the Past Revolutionary Experiences in 1848 1. Examine the French newspaper. What does it reveal about the rise of mass politics in 1848? • Greater involvement in politics: The triumphant image of the French newspaper, along with its title (The Public Safety), point to the idea that a great many people, particularly those from the lower class who had been alienated from political thought or discussion, were involved in the mass politics of 1848. The eight-fold increase in daily newspaper production allowed political ideas and news to reach more people. • Violent involvement in politics: The image from the newspaper, which shows people storming a barricade and carrying weapons, also suggests that mass politics in 1848 was not a nonviolent movement. Political disputes resulted in clashes between central governments and protestors and reformers. 2. The 1848 revolutions increased political activity, yet they were crushed. How does the scene of fighting in Frankfurt help to explain this outcome? 389 • Well-trained and well-armed armies: The street fighting in Frankfurt shows rows of disciplined, heavily armed soldiers facing off against an unruly mob crowded behind a makeshift barricade. The training and equipment advantage (like the heavy artillery mentioned in the feature) shown in the picture tells us that armies still under the control of the central government could crush almost any revolution, unless it was extremely wellorganized. 3. Consider Meissonier’s Memory of the Civil War. In what ways do societies transmit and revise their historical memories? • Historical memories: Though the feature states that Meissonier was a French soldier, his painting does not celebrate the destruction of the rebellion. Instead, it sadly reflects on the loss of life, shown through the ragged, bloody bodies painted on the city street. Societies in the nineteenth century would have transmitted or revised their historical memories through paintings, novels, or poems. Modern societies would use these methods, but would add photographs, film/television, or Web content as ways of preserving these memories. LECTURE STRATEGIES See also the maps and images for presentation in Additional Bedford/St. Martin’s Resources for Chapter 22, below. Lecture 1: Pursuing Equilibrium: European International Relations after 1815 War had punctuated Europe’s eighteenth century. The nineteenth century was far more peaceful, at least within the boundaries of Europe.After the disasters of the Napoleonic Wars, European states moved from an international system based on the principle of balance of power to one that emphasized equilibrium. It was a remarkably successful transformation, one that maintained European political stability for nearly a century. For students interested in international relations, this lecture provides an opportunity for a short tutorial on the history of diplomacy. Originating around 1500 in the Italian city-states, international diplomacy blossomed after the Treaty of Westphalia (1648). By the eighteenth century, the guiding European diplomatic principle was to maintain a balance of power, which (some historians argue) created a structure that promoted war rather than 390 C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS prevented it. Fiscal and military limitations, rather than diplomacy, were the main reasons why more wars did not occur in the eighteenth century. But the Napoleonic Wars began to forge a new international system. Recap the impact of the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars on Europe. Napoleon’s armies transformed war into a total affair, demanding the mobilization of whole populations and aiming to destroy armies rather than just occupy land. To ward off the French contagion, European nations forged a series of coalitions, including some unlikely alliances (e.g., Britain and Russia) that paved the way for more coalition building in the post-Napoleonic era. By 1813 the coalition partners had shifted their goals from warmaking to peacemaking and their diplomatic strategies from coercion to persuasion. The Congress of Vienna was pivotal in forging the new international system. Draw out the nuances of the agreement: key provisions included the congress system within the Concert of Europe; a system of intermediate bodies as buffers and spheres of influence; and the fencing off of Europe from external conflicts (i.e., Europeans could penetrate the rest of the world without having much effect on intra-European politics). Of course, inherent weaknesses continued: Britain tended toward isolationism; Austria-Hungary was threatened by nationalist movements; Prussia grew increasingly ambitious; and Russia was increasingly rigid. But the system held together relatively well, regardless. Sources: Paul W. Schroeder, The Transformation of European Politics, 1763–1848 (1994); F. R. Bridge and Roger Bullen, The Great Powers and the European States System, 1815–1914 (1980); T. Chapman, Congress of Vienna: Origins, Processes, Results (1998). Lecture 2: Competing for Legitimacy: Conservatism, Liberalism, and Socialism Political theory is not the most compelling topic for history students, but this lecture can be enlivened with references to vivid personalities and dramatic events. Emphasize the enduring nature of the questions raised in the post-1815 period: How best to create political and economic stability? What should be the balance between individual freedom and state authority? Begin with the conservative agenda. Claiming “legitimacy,” Conservatives believed the answers lay in long-established political, economic, and cultural systems: monarchy, aristocracy, and organized religion (illustrate this principle by showing students Heinrich Olivier’s The Holy Alliance [1815]). As the case study, Metternich is a fascinating individual who has left a vast correspondence revealing his political convictions. After explaining the conservative position, explore the threats to Metternich’s vision. German universities and student fraternities provide interesting case studies in resistance, as do the nationalist movements in Greece, Hungary, Italy, and elsewhere. Help students see Metternich’s system within a wider context of revolt and reform: in 1831– 1832, England was torn apart by riots in favor of the Reform Bill; the election of President Jackson in the United States signaled change; and South American struggled for independence from Spain—these all suggest that Metternich’s system was flowing against the tide. But urge students to resist the tyranny of hindsight and recognize that Metternich’s system was not necessarily doomed from the start, and not all monarchists were evildoers. Liberalism is perhaps the easiest of the three to explain, as students find it the most familiar, but make sure they have their definitions straight. Nineteenth-century liberalism is not the same as the “l-word” so readily tossed around by today’s political pundits. The life and commitments of John Stuart Mill, in partnership with his wife Harriet, can serve as one case study of liberalism (and allow you to include a discussion of feminism as one piece of the liberal creed). The British response to the Irish famine is another. Finally, because socialism is so misunderstood, it is important to explain it carefully and with enough detail so that students can understand its appeal, to so many, for such a long time. Show students that socialism’s early versions differed considerably from the Stalinist versions they might know. Marx, of course, deserves ample time, but so do other early socialists: Pierre Proudhon’s assertion that “Property Is Theft” bears close examination, as does Robert Owen’s experiments in social harmony. Norman Davies’s Europe: A History (1998) contains a very useful chart labeled “The Pedigree of Socialism,” which highlights socialism’s many variants. Sources: Albert S. Lindemann, A History of European Socialism (1983); Robert Gildea, Barricades and Borders: Europe 1800–1914 (1996); Henry A. Kissinger, A World Restored (1973); Paul Johnson, The Birth of the Modern (1991). Lecture 3: The Bohemian Revolt This topic is too good to skip. The artistic and literary responses to the dual revolution are a delight C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS to teach and often strangely relevant to students’ worlds. Begin with the basics. Introduce the broad historical context, exploring its birth within Enlightenment thought (Jean-Jacques Rousseau) and its growth during the French Revolution and Napoleonic Wars. Lay out the geography: it was particularly strong in Britain, France, and the Germany confederation. Explore its social dynamics: its adherents included both men and women and from a variety of class backgrounds. Then delve into the romantics’ key ideas and attitudes: exuberance, imagination, spontaneity, and strenuous living. One key idea was their rejection of bourgeois values. Gustav Flaubert signed his letters with the title “Bourgeoisophobus,” and claimed that hatred of the bourgeoisie was “the beginning of all virtue.” The romantics condemned the moneymaking bourgeoisie as dull, crass, conformist, and, worst of all, unheroic. They flocked to run-down neighborhoods, lived in garrets, wore beards and long hair, and adopted flamboyant dress. One might argue they were the first purveyors of a “lifestyle.” Give examples of how, in their art, poetry and music, the romantics often strove to shock: tell the story of how poet Gérard de Nerval took a lobster on a walk in the Tuileries gardens. The romantics wrote about suicide and sometimes committed it. They identified with the victims of the bourgeois order: the poor, criminals, those struggling for nationhood. Some elevated sex to an art form. Of course, a critique is also necessary. Many of the romantic artists were bourgeois themselves; they were cultivated and sophisticated individuals who were never as antimaterialist as their rhetoric suggested. But they celebrated creativity, rebellion, novelty, self-expression, anti-materialism, and heroism nonetheless. Turn the lecture into a holistic experience by sharing plenty of examples of the art, poetry, and music of the movement. If slides are available, the grandiose paintings of Theodore Gericault (The Raft of the Medusa [1819]) and Eugene Delacroix (Massacre at Chios [1824]) are not to be missed. Sources: Isaiah Berlin, The Roots of Romanticism (1999); Boris Ford, ed., The Romantic Age in Britain (1992); Cwisfa Lim, Romanticism: Dawn of a New Era (2002); Iain McCalman, The Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age (1999; available online by subscription). 391 COMMON MISCONCEPTIONS AND DIFFICULT TOPICS 1. Liberalism and the Corn Laws The premise of the Corn Laws is simple—they were import tariffs adopted in 1815 to protect British agriculture (in British lingo, corn refers to wheat, rye, and barley, not maize). But their application and effects are more difficult to understand. The laws prevented the importation of foreign-grown corn until domestically grown corn reached a certain price (initially £4 per quarter, with a quarter meaning a unit of eight bushels). Perhaps more challenging for students to understand is how the Corn Laws became a tool of class warfare. They were designed to protect large landowners, not the small tenant farmers, and to keep the price of grain—and therefore bread—high. In a defense of the Corn Laws, Benjamin Disraeli argued that their repeal would destroy the “territorial constitution” of Britain by empowering commercial interests. The greatest champion of repealing the Corn Laws, Prime Minister Sir Robert Peel, saw it more as a way heading off revolution than as an act of liberal economic reform. 2. Early Nationalism Given our familiarity with nationalism’s twentiethcentury versions, it is easy to misunderstand the origins and nature of nationalism in the nineteenth century. Nationalism was a doctrine invented in Europe during the Napoleonic Wars that asserted that humanity is naturally divided into nations, and that nations should form the bases of states and state power. Prior to this time, the monarch had most often embodied the nation (e.g., Louis XIV’s “l’etat, c’est moi”). The roots of nationalism can be found in the Enlightenment’s and the French Revolution’s emphasis on liberal democracy and fundamental human rights (i.e., nationalism as a doctrine of “popular sovereignty”), but as time passed nationalism increasingly became a tool for denying the right of national self-determination (to Africans, Asians, and revolutionary Europeans). Generally, nationalism can take two different forms: (1) nationalism as loyalty to an existing state (patriotism), or (2) nationalism as liberation—the desire to create a new state based on identities, whether religious, ethnic, cultural, or linguistic. 392 C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS Sources: Geoff Eley and Ronald Grigor Suny, eds., Becoming National: A Reader (1996); Eric Hobsbawm, Nations and Nationalism Since 1780 (1990); Elie Kedourie, Nationalism (1960). IN-CLASS ACTIVITIES Using Film and Television in the Classroom When it first appeared, Civilization: A Personal View by Lord Clark (1969) was labeled by one critic as “the definitive documentary series of the last fifty years” and “eternally significant.” Though now dated, it still offers gorgeous visuals and useful insights into the history of Western art, architecture, and philosophy. For the nineteenth century, try episode eleven (“The Worship of Nature”) on the glorification of nature as a creative force and spark behind the romantic movement. Other documentaries on the romantic movement include Simon Schama’s The Power of Art: Turner—Painting Up a Storm (2007, 50 min.) and the three-episode series The Romantics (Films for the Humanities and Social Sciences, 2006, 60 min. each), which uses creative reenactments to explore the lives and works of William Blake, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Wordsworth, Lord Byron, and Percy and Mary Shelley. Many feature-length films on the romantic movement seem to reflect the adage “don’t let the facts stand in the way of a good story.” The premise of the film Immortal Beloved (1994, 121 min.) is speculative—that Beethoven’s enduring love interest was his brother’s wife—and as one reviewer put it, the whole question is “less a great mystery than a minor curiosity.” But well-selected clips can help introduce this temperamental genius and his music to students. Look for the segment set against the Ninth Symphony. Other films about Beethoven can be found at http://www.lvbeethoven.com/Fictions/ FictionFilmsImmortalBeloved.html. Another option is Impromptu (1999, 107 min.), about the romance between Chopin and George Sand, but its preoccupation with sexual promiscuity suffers from historical anachronism and may disqualify it from classroom viewing. Or check out the classic Chopin biography, A Song to Remember (1945, 113 min.), but keep an open eye for historical errors. Paris continued to be at the center of the cultural and political movements of the age. Paris: 1830 (1997, 14 min.) introduces students to the monuments to France’s glory days (Arc de Triomphe, the Pantheon, and the Place de Concorde), as well as the romantic artists and musicians who made Paris their home, while Victor Hugo: Les Misérables (1997. 3 hrs. 48 min.) dramatizes Hugo’s novel and provides a riveting social portrait of midcentury Paris. (Both films are available from Films for the Humanities and Social Sciences.) Of course, you might also show students portions of Les Misérables (1998, 134 min.), which many mistakenly believe to be set in 1789 but is actually is set against the backdrop of the antimonarchist Paris uprising of June 1832. With its intrinsic drama, the Great Famine in Ireland is surprisingly unrepresented on screen. On the one hundred and fiftieth anniversary of the potato blight, the BBC produced a documentary The Great Irish Famine (1996), but if you use it, ask students to compare its tone and slant to that presented by other historians, such as Christine Kinealy and Cormac O’Grada. Part one of the acclaimed PBS series The Irish in America: Long Journey Home (1997, 86 min.) focuses on the emigration that resulted from the potato blight. Class Discussion Starters 1. What relationship does feminism have to other mid-century “isms” and ideologies? Modern feminism—a complex doctrine in itself— emerged from within various ideological traditions. While liberalism, with its emphasis on individual rights, is often recognized as the main source of feminism, socialist and nationalist movements also brought women’s interests forward. Guide students in a discussion of utopian socialists’ views of free love or Frederick Engels’ writings on the family. Point out women’s involvement in the nationalist movements of 1848, and remind students of one, often ignored “ism” that also shaped early feminism: evangelicalism. Sources: Jane Rendall, The Origins of Modern Feminism: Women in Britain, France, and the United States, 1780–1860 (1990); Bonnie Smith, Changing Lives: Women in European History Since 1700 (1989); Sue Morgan and Jacqueline deVries, eds., Women, Gender, and Religious Cultures in Britain, 1800–1940 (1910). 2. Why did the revolutions of 1848 fail? No simple response will suffice. Generally, you can point to divisions among the revolutionaries as the C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS reason for the downfall—for example, splits between bourgeois liberals and working-class street fighters— but to answer the question well, students must understand local variations. In Hungary, for example, anti-Jewish riots sparked by the prospect of Jewish enfranchisement, and Croatian opposition to Hungarian rule, were significant factors. The revolutions of 1848 demonstrated, once again, that it is easier to bring down a regime than to build one up. Historical Debates The plight of the Irish during the Great Famine rarely fails to capture the interest of students. Was the disaster inevitable or avoidable? Should the British have done more to relieve distress? If so, what could have been done differently? How did prevailing political and economic ideologies shape the responses? You might give students contrasting historical assessments and have them decide which is more convincing (F. S. L. Lyons, for example, called the initial response “prompt and relatively successful,” while others like historian Christine Kinealy are more critical). However, a debate staged with historical actors is more engaging (albeit timeconsuming) and can elicit nuances in the various historical responses. As you prepare students for the debate, urge them to remember the complexity of the Irish situation in the 1840s. As William Thackeray observed “To have an opinion about Ireland, one must begin by getting at the truth; and where is that to be had in the country? Rather, there are two truths, the Catholic truth and the Protestant truth….Belief is a party business” (Irish Sketch Book [1842].) Students will quickly learn that there were, in fact, more than two truths. For this debate to work, students will need a thorough knowledge of AngloIrish politics and society. Among Irish landlords, some behaved well (the Earl of Kingston spent half his annual income relieving distress), while others behaved badly (refusing to lower rents and evicting tenants). Irish tenant farmers also responded differently, depending on their region and relative prosperity. Similarly, attitudes among the British varied greatly, reflecting a range of perceptions and prejudices. Sometimes ideology was to blame for the ad hoc, haphazard, and ill-planned responses; at other times it was basic incompetence. Make sure the students draw out the ideological underpinnings where applicable and address how the ideas of Adam Smith, Thomas Malthus, and David Ricardo played a role. Students will have fun choosing parts: on the 393 British side, Prime Minister Robert Peel, Lord John Russell, Sir Charles Trevelyan, Lord Lieutenant of Ireland, Queen Victoria, and some Quakers; on the Irish side, Daniel O’Connell, John Mitchel (“Young Ireland”), Lord Mayor of Dublin, some landlords, and of course their tenant farmers. Sources: Helen Litton, The Irish Famine: An Illustrated History (2003); Christine Kinealy, A Death-Dealing Famine: The Great Hunger in Ireland (1997); Edward Lengel, The Irish Through British Eyes: Perceptions of Ireland in the Famine Era (2002); Cecil Woodham-Smith, The Great Hunger, 1945–49 (1991); various books by Cormac Ó Gráda. Using Primary Sources Excerpts are always an option, but the full-length versions of the era’s classics are well worth the investment of time. Three that work well are Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein; or, the Modern Prometheus (1818), Alexis de Tocqueville, Democracy in America (1835), and Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, The Communist Manifesto (1848). As students encounter these texts, give them background on the authors’ lives, views, and motivations. Discuss the forms of the texts, too: for example, both Tocqueville and Marx were writing polemic works— that is, writing to advocate causes. These texts were not, nor were they intended to be, balanced scholarly treatises. Polemic works usually promote an authors’ viewpoint and summarily dismiss opposing arguments. Because of this, you might invite students to “talk back” to these texts, making counterarguments with historical evidence. Cooperative Learning Activities 1. American Idol: The Romantics Music is such a potent tool for teaching history that it would be a shame not to engage students with the masterpieces of romantic music. One alternative to the “research and report” approach is a competition in the format of American Idol. Ask students to come to class as their chosen personas, introduce themselves (with some personal details), and then play a five- to ten-minute selection for a panel of “judges.” They might choose to be Frederic Chopin, Ludwig van Beethoven, Franz Liszt, Hector Berlioz, Johannes Brahms, Edvard Grieg, Clara Schumann, Pyotr Tchaikovsky, or another composer or 394 C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS performer from the period. The panel of judges can applaud, hiss, and ask questions about harmony, form, tonality, or something more personal. A student who comes as Chopin and plays an excerpt from the “Revolutionary Étude” (op. 10 no. 12), for example, should be prepared to explain that it was inspired by the Polish revolution of 1831. Sources: Alex Zukas, “Different Drummers: Using Music to Teach History,” Perspectives (September 1996). 2. Mapping the 1848 Revolutions Like 1989, the year 1848 brought enormously complex political changes. A series of liberal revolutions exploded around Europe, in France and Hungary, Milan and Sicily, and across the German states. Some clamored for liberal constitutions, others for nationhood, and still others for workers’ rights. But who can keep it all straight? Give students a blank map of Europe and ask them to map the revolts, indicating the central issues, key leaders, and major turning points and outcomes. Sources: Mike Rapport, 1848: Year of Revolution (2009); Jonathan Sperber, The European Revolutions, 1848–1851 (1994). Web Resources Delacroix (http://cgfa.sunsite.dk/delacroi/index.html) Edgar Allan Poe Museum (www.poemuseum.org) Encyclopedia of 1848 Revolutions (http://cscwww .cats.ohiou.edu/~Chastain) The History Place: Irish Potato Famine (www.historyplace.com/worldhistory/famine/ index.html) Interpreting the Irish Famine, 1845–1850 (www.xroads.virginia.edu/~hyper/sadlier/irish/ Famine.htm) The Nationalism Project (www.nationalismproject .org/) Utopian Socialism Archive (www.marxists.org/ subject/utopian) Victor Hugo Central (www.gavroche.org/vhugo) The Walter Scott Digital Archive (www.walterscott .lib.ed.ac.uk) William Wordsworth: The Complete Poetical Works (www.bartleby.com/145) Additional Bedford/St. Martin’s Resources for Chapter 22 Instructor’s Resource CD-ROM The chapter-specific resources on this disc are useful for presentation, handouts, and quizzing from within lecture presentations. The disc includes a chapter outline in PowerPoint format, multiple-choice questions in Word and PowerPoint format for use with the i>clicker classroom response system, as well as the following maps and images from the textbook, in both PowerPoint and jpeg formats: • The Triumph of Democratic Republics • Map 22.1: Europe in 1815 • Map 22.2: Peoples of the Habsburg Monarchy, 1815 • Spot Map 22.1: 1820 Revolts in Spain and Italy The PowerPoint chapter outlines with embedded images and maps are also available in the online instructor’s resource section of the book companion site at bedfordstmartins.com/mckaywest. These maps and selected images are also available in jpeg format from the Make History section of the book companion site. The Bedford Series in History and Culture Volumes from the Bedford Series in History and Culture can be packaged at a discount with A History of Western Society. Relevant titles for this chapter include: • European Romanticism: A Brief History with Documents, Warren Breckman, University of Pennsylvania • THE COMMUNIST MANIFESTO by Karl Marx and Frederick Engels with Related Documents, Edited with an Introduction by John E. Toews, University of Washington To view an updated list of series titles, visit bedfordstmartins.com/history/series. Online Study Guide at bedfordstmartins.com/mckaywest The Online Study Guide helps students review material from the textbook as well as practice historical skills. Each chapter contains assessment quizzes, short-answer and essay questions, and interactive activities accompanied by page references to encourage further study. The following map, visual, and document activities, based on textbook C HAPTER 22 • I DEOLOGIES AND U PHEAVALS activities and special features, are available in the Online Study Guide for this chapter as assignable quizzes: • Visual Activity: The Triumph of Democratic Republics • Map Activity: Map 22.1: Europe in 1815 395