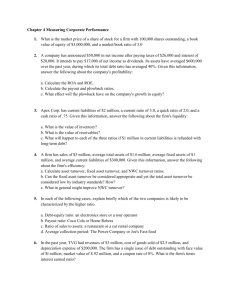

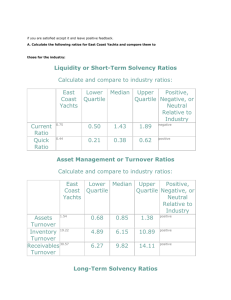

Wood-harvesting enterprise financing and investment

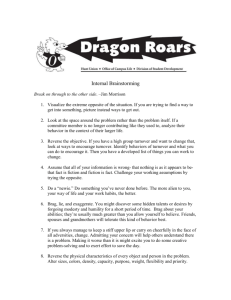

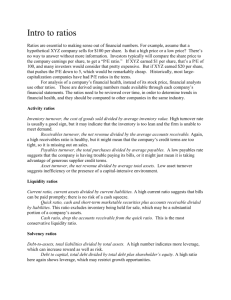

advertisement