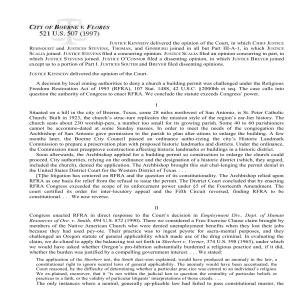

CITY OF BOERNE v. FLORES, 521 U.S. 507 (1997) JUDICIAL

advertisement

CITY OF BOERNE v. FLORES, 521 U.S. 507 (1997) JUDICIAL HISTORY: The Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA) of 1993 was held by the Supreme Court of the U.S. to be an excessive use of power under section: 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment of the United states Constitution. On appeal from the Fifth Circuit's reversal of a District Court's finding against Archbishop Flores, the Court granted Boerne's request for certiorari. Facts: Archbishop of San Antonio sued local zoning authorities for violating his rights under the RFRA of 1993, by denying him a permit to expand his church. Zoning authorities argued that the Archbishops church was located on a historic preservation district governed by an ordinance forbidding new construction, and that the RFRA was unconstitutional insofar as it sought to override the preservation ordinance. Issue: Did Congress exceed its Fourteenth Amendment enforcement powers by enacting the RFRA which, in part, subjected local ordinances to federal regulation. Did the RFRA is a proper exercise of Congress’ Section:5 power to “enforce” by “appropriate legislation” the constitutional guarantee that no state shall deprive any person of “life, liberty, or property without the due process of law” nor deny any person “equal protection of the laws?” Law and Rules: While preventive rules are sometimes appropriate remedial measures, there must be a congruence between the means used and the ends sought to be achieved. The appropriateness of remedial measures must be considered in light of the evil presented. Discussion/ Analysis: On review, the court held that Congress was afforded broad powers under the Enforcement Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. However, in most cases, the state laws to which RFRA applied were not ones motivated by religious bigotry and, thus, the RFRA was not considered remedial or preventative legislation. The court determined that the RFRA appeared to be an attempt to invoke substantive change in constitutional protections. Thus, the court held that the RFRA was unconstitutional because it allowed considerable Congressional intrusion into the states' general authority to regulate for the health and welfare of their citizens. Conclusion: Yes. Under the RFRA, the government is prohibited from "substantially burden[ing]" religion's free exercise unless it must do so to further a compelling government interest, and, even then, it may only impose the least restrictive burden. The Court held that while Congress may enact such legislation as the RFRA, in an attempt to prevent the abuse of religious freedoms, it may not determine the manner in which states enforce the substance of its legislative restrictions. Significance: This decision disavowed any power on Congress’ power to confer new substantive rights not derived from prior decisions of the Court interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment. Thus, this case is important because it illustrates that Congress does not have unlimited power to create new substantive rights. Rather, it must look to the Court’s interpretations of the Fourteenth Amendment to find such rights.