Maine-religious-liberty-bill-background-Revised

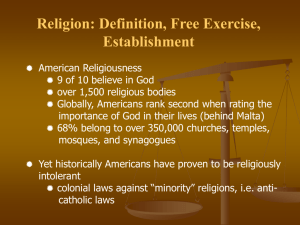

advertisement

Maine Religious Liberty Bill Background and Summary The religious liberty bill proposed by Senator Burns is considered a Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA).The primary goal of this bill is to prohibit the Maine government from burdening Mainers’ free exercise of religion without strong justification. This type of bill is not unique to Maine. In 1993, Congress passed a federal RFRA and, as of October 2013, at least 18 other states have passed their own RFRAs. The following is a brief history of RFRAs that will hopefully provide some historical background. For the first 150 years of American history, the U.S. Supreme Court had few occasions to rule on religious liberty cases (whether it was establishment clause cases or free exercise clause cases). This began to change in the latter half of the twentieth century. In 1963, a case came before the U.S. Supreme Court in which a Seventh-Day Adventist claimed that South Carolina’s unemployment compensation law violated her free exercise of religion. In the case, Sherbert v. Verner, the U.S. Supreme Court announced a test by which it would judge the validity of laws burdening the free exercise of religion. Under this test, a law substantially burdening the free exercise of religion would only be valid if the law: 1. served a compelling state interest and 2. was accomplished by the least restrictive means possible Any law not meeting the above criteria would be struck down as an unconstitutional infringement upon the free exercise of religion. This stringent test is often called the “compelling interest test” or the Sherbert rule. In the 1990 case Employment Division v. Smith, the U.S. Supreme Court abandoned the compelling interest test, opting instead for a much more lenient standard by which to evaluate laws burdening the free exercise of religion. Under the new standard, a law burdening the free exercise of religion would be considered Constitutional if it: 1. was neutral toward religion and 2. generally applicable to all persons The standard ruled down by Smith made it much easier for the government to infringe upon religious liberty. Many laws that burdened religion could easily be considered “neutral” and “generally applicable.” The response to Smith was fierce. At the time, the Harvard Law Review argued that the Smith decision “eviscerated” and “gutted” much of the First Amendment’s protection for the free exercise of religion. A large, politically-diverse coalition, including such groups as the ACLU and the Christian Legal Society, opposed the Court’s ruling and pushed Congress to respond. In 1993, Congress passed the federal Religious Freedom Restoration Act (RFRA), which restored the compelling-interest standard to claims concerning the free exercise of religion. This law applied to the federal government and to the states. In 1997, however, the U.S. Supreme Court declared, in the case City of Boerne v. Flores, that the application of the RFRA to the states was unconstitutional. Consequently, the federal RFRA still applies to the federal government, but not to the states. In the wake of the Smith and Boerne cases, many states passed their owns RFRAs, restoring the compelling interest standard in evaluating state and local laws that burden (or substantially burden) the free exercise of religion. The aim of the proposed religious liberty bill for Maine is the same as other state RFRAs- to prevent the government from being able to easily infringe upon citizens’ right to freely exercise their religion. Specifically, the bill would do the following: 1. Restore the compelling interest test and guarantee its application in all cases where the exercise of religion is burdened by state action, and 2. Provide a claim or defense to a person or persons whose exercise of religion is burdened by state action