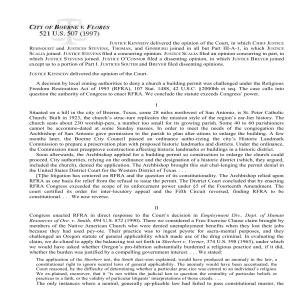

City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997) (The Religious

advertisement

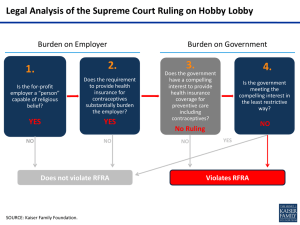

City of Boerne v. Flores, 521 U.S. 507 (1997) (The Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 was held unconstitutional on the grounds that the law went beyond Congress’ authority to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment, which is remedial only.) Summary prepared by John M. Mattox Succinct Summary The Catholic Archbishop of San Antonio applied for a building permit to enlarge a parish church, built in 1923, in Boerne, Texas. Under an ordinance that had recently been passed by the city council, the city’s Historic Landmark Commission had to preapprove construction affecting historic landmarks or buildings in the historic district. Relying on this ordinance, city officials denied the Archbishop’s application. The Archbishop challenged the denial under the Religious Freedom Restoration Act of 1993 (RFRA). The Court held that Congress’ enactment of RFRA was not a proper exercise of its enforcement power under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court explained it contradicted important principles that maintain the separation of powers framework and the federal-state balance. Contrasting RFRA with the Voting Rights Act of 1965—whose enactment the Court upheld as a legitimate use of Congress’ enforcement power under the Fourteenth Amendment— the Court explained that RFRA’s legislative record lacked examples of instances of generally applicable laws passed because of religious bigotry in the past 40 years. More problematic for the Court, however, was the fact that RFRA was out of proportion to the remedial power vested in Congress by the Fourteenth Amendment. Instead of responding to or preventing unconstitutional behavior, the Court viewed RFRA as attempting a substantive change in constitutional protections. In addition, RFRA was unconstitutional because it was not adapted to the wrong which the Fourteenth Amendment was intended to provide against. Facts of the Case St. Peter Catholic Church, located in Boerne, Texas—approximately 28 miles from San Antonio—was too small for its growing parish. Church leaders, therefore, undertook plans to enlarge that building, which had been built in 1923. Shortly thereafter, the Boerne City Council passed an ordinance authorizing the city’s Historic Landmark Commission to prepare a preservation plan with proposed landmarks and districts. Under the ordinance, the commission had to preapprove construction affecting historic landmarks or buildings in a historic district. After the ordinance was enacted, the Archbishop of San Antonio applied for a permit to enlarge St. Peter. City authorities, relying on the ordinance and the designation of an historic district, denied the permit. The Archbishop challenged the denial under RFRA in U.S. District Court. The District Court held that Congress had exceeded its authority under Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment in enacting RFRA. On an interlocutory appeal, the Fifth Circuit reversed. Issue Presented to the Court Boerne v. Flores Summary Page 1 The issue before the Court was whether Congress’ enactment of RFRA exceeded its power to “enforce” the guarantees in the Fourteenth Amendment by “appropriate legislation.” Finding and Conclusion RFRA was enacted as a direct response to the Court’s Employment Div., Dept. of Human Resources of Oregon v. Smith decision. Its stated purposes were to restore the compelling interest test as set forth in Sherbert v. Verner, 374 U.S. 398 (1963) and to guarantee its application in all cases where free exercise of religion is substantially burdened. RFRA prohibited “government” from “substantially burden[ing] a person’s exercise of religion even if the burden results from a rule of general applicability unless the government can demonstrate the burden ‘(1) is in furtherance of a compelling governmental interest; and (2) is the least restrictive means of furthering that compelling governmental interest.’” Id. at 515-516. Congress relied on its enforcement power in Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment to impose RFRA’s requirements on the States. The Court explained that while Congress’ enforcement power under Section 5 is broad, it is not unlimited. The Court stated: Congress’ power under § 5, however, extends only to enforcing the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court has described this power as remedial. The design of the Amendment and the text of § 5 are inconsistent with the suggestion that Congress has the power to decree the substance of the Fourteenth Amendment’s restrictions on the States. Legislation which alters the meaning of the Free Exercise Clause cannot be said to be enforcing the Clause. Congress does not enforce a constitutional right by changing what the right is. It has been given the power to enforce, not the power to determine what constitutes a constitutional violation. Were it not so, what Congress would be enforcing would no longer be, in any meaningful sense, the provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment. Id. at 519 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted). The Court undertook an extensive review of the Fourteenth Amendment’s history and its own jurisprudence and concluded that both confirm the remedial, rather than substantive nature of Congress’ Fourteenth Amendment enforcement power. The Court found that RFRA was not a proper exercise of the remedial enforcement power conferred by the Fourteenth Amendment. Indeed, it reasoned: . . . RFRA cannot be considered remedial, preventive legislation, if those terms are to have any meaning. RFRA is so out of proportion to a supposed remedial or preventive object that it cannot be understood as responsive to, or designed to prevent, unconstitutional behavior. It appears, instead, to attempt a substantive change in constitutional protections. Preventive measures prohibiting certain types of laws may be appropriate when there is reason to believe that many of the laws affected by the congressional enactment have a significant likelihood of being unconstitutional. Remedial legislation under § 5 should be adapted to the Boerne v. Flores Summary Page 2 mischief and wrong which the Fourteenth Amendment was intended to provide against. RFRA is not so confined. Id. at 532 (internal citations and quotation marks omitted). The Court further held that the “stringent test RFRA demands of state laws reflects a lack of proportionality or congruence between the means adopted and the legitimate end to be achieved.” Id. at 533. Based on these considerations, the Court concluded that RFRA “contradicts vital principles necessary to maintain separation of powers and the federal balance” and was an unconstitutional exercise of power. Boerne v. Flores Summary Page 3