Smith v. Allwright (1944) - voter discrimination S.S. Allwright, a TX

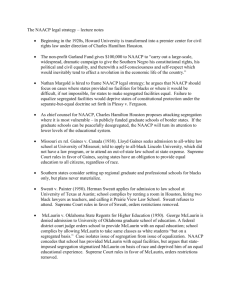

advertisement

Smith v. Allwright (1944) - voter discrimination S.S. Allwright, a TX county election official denied Lonnie E. Smith, a black man, the right to vote in the 1940 Texas Democratic primary after the TX Sup Ct classified the party a "voluntary association," who allowed only whites to participate in primary elections. The decision was based on the 1935 US Sup Ct finding in Grovey v. Townsend, that the fed gov had no authority over primaries, which were under the direction of private political parties. In an 8-1 decision the Court agreed with the argument presented by Smith’s attorney (Thurgood Marshall) and overruled its earlier finding in Grovey v. Townsend (1935) declaring restrictions against blacks unconstitutional. Even though the Democratic Party was a voluntary organization, because TX statutes governed the selection of county-level party leaders, the party conducted primary elections under state statutory authority, and state courts were given exclusive original jurisdiction over contested elections, guaranteed for blacks the right to vote in primaries. Allwright engaged in state action abridging Smith's right to vote because of his race. A state cannot "permit a private organization to practice racial discrimination" in elections, argued Justice Reed. The Smith decision is considered one of the major victories of the early Civil Rights movement. It was especially significant in the development of the public function concept, which views many activities as state actions even when performed by private actors. Texas Democrats tried to circumvent Smith by establishing the Jaybird Democratic Association, but the effort was invalidated in Terry v. Adams (1953), the last of the white primary cases. Morgan v. Virginia (1946) - segregation in interstate bus transportation. In the spring of 1946, Irene Morgan, a black woman, boarded a bus in VA to go to Baltimore, MD. Morgan was ordered to sit in the back of the bus, as VA state law required. She objected, saying since she was riding an interstate bus, VA law did not apply. Morgan was arrested and fined ten dollars. Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP took on the case arguing that because an 1877 Sup Ct decision ruled it was illegal for states to forbid segregation, it was likewise illegal for states to require it. The Sup Ct agreed saying: "As no state law can reach beyond its own border nor bar transportation of passengers across its boundaries, diverse seating requirements for the races in interstate journeys result. As there is no federal act dealing with the separation of races in interstate transportation, we must decide the validity of this Virginia statute on the challenge that it interferes with commerce, as a matter of balance between the exercise of the local police power and the need for national uniformity in the regulations for interstate travel. It seems clear to us that seating arrangements for the different races in interstate motor travel require a single, uniform rule to promote and protect national travel. Consequently, we hold the Virginia statute in controversy invalid." The Ct ruling did not impact segregated transportation within a state. Shelley v. Kraemer (1948) - Segregation and housing Kraemer and other white property owners governed by a restrictive covenant brought suit in IL state court seeking to block an African-Am family, the Shelleys, from owning property. Kraemer lost at trial, but on appeal the MO Sup Ct reversed the decision and ruled the covenant did not violate Shelleys' constitutional rights. The Shelleys appealed the case to the US Sup Ct. In a unanimous verdict, the Sup Ct ruled a court may not constitutionally enforce a “restrictive covenant” which prevented people of certain race from owning or occupying property arguing the Fourteenth Amendment prohibited discrimination by “State action.” “Although the contract itself was private, the plaintiff in the litigation had sought assistance of the State court in enforcing the contractual provisions. . . . . [A]ction of State courts and of judicial officers in their official capacities is to be regarded as action of the State within the meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment.” The Ct concluded: “W e have no doubt that there has been State action in these cases in the full and complete sense of the phrase. The undisputed facts disclose that petitioners were willing purchasers of properties upon which they desired to establish homes. The owners of the properties were willing sellers; and contracts of sale were accordingly consummated. It is clear that but for the active intervention of the State courts, supported by the full panoply of State power, petitioners would have been free to occupy the properties in question without restraint.” Accordingly, State judicial enforcement of restrictive covenants based on race denies equal protection of laws in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. Alger Hiss Case (1949) – Red Scare/espionage In August 1948, W hittaker Chambers, a former Communist appearing before the House Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), charged that Alger Hiss, president of the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, was a Communist spy. Chambers claimed that Hiss had belonged to the same espionage ring and had given him (Chambers) secret St Dept documents. Chambers later repeated these charges on "Meet the Press." Hiss, a Harvard-educated lawyer and a prominent W ashington figure, was responsible for Far East affairs in the St Dept and played a significant role in planning for and development of the United Nations. Hiss responded to Chambers's charges by suing Chambers for slander. Chambers subsequently produced copies of secret documents, saying they had been hidden in a pumpkin in a field near his farm. Since the statute of limitations for espionage had expired, the gov prosecuted Hiss for perjury. Hiss’ first trial ended in a hung jury; at the second Hiss was found guilty and sentenced to five years in prison. Julius & Ethel Rosenberg Case (1950) – Red Scare/espionage In 1950, the FBI arrested Julius Rosenberg and his wife Ethel. They were indicted for conspiracy to transmit classified military information to the Soviet Union. During the trial, the gov charged that in 1944 and 1945 the Rosenbergs had persuaded Ethel's brother, David Greenglass, an employee at the Los Alamos atomic bomb project, to provide them and a third person, Harry Gold, with top-secret data on nuclear weapons. Most evidence against the Rosenbergs came from Greenglass and his wife, Ruth. The Rosenbergs were found guilty in 1951 and sentenced to death. Morton Sobell, a codefendant, received a thirty year prison term, as did Harry Gold. David Greenglass was sentenced to fifteen years. Despite several appeals and pleas for executive clemency, the Rosenbergs were executed June 19, 1953. They became the first US civilians sentenced to death in an espionage trial. The case aroused much controversy. Many claimed the political climate made a fair trial impossible and the only seriously incriminating evidence came from a confessed spy. Others questioned the value of information transmitted and argued the death penalty was too severe. Communists in the US and abroad organized a campaign to save the Rosenbergs as did many liberals and religious leaders. Sweatt v Painter (1950) – discrimination The case involved a black man, Heman Marion Sweatt, who was refused admission to the University of Texas School of Law in 1946 on the grounds that the Texas State Constitution prohibited integrated education. At the time, no law school in Texas would admit blacks. The Texas trial court, instead of granting the plaintiff a writ of mandamus, continued the case for six months allowing the state time to create a law school only for blacks. The trial court decision was affirmed by the Ct of Civil Appeals and the TX Sup Ct denied writ of error on further appeal. Sweatt and the NAACP appealed to the US Sup Ct. Thurgood Marshall was one of two lawyers who presented Sweatt's case. In a unanimous decision, the Ct held that the Equal Protection Clause required that Sweatt be admitted to the university. The Court found that the "law school for Negroes," which was to have opened in 1947, would have been grossly unequal to the Univ of TX Law School. The Ct argued the separate school would be inferior in a number of areas, including faculty, course variety, library facilities, legal writing opportunities, and overall prestige. The Ct also found that the mere separation from the majority of law students harmed students' abilities to compete in the legal arena. The finding cited the following differences in facilities between the Univ of TX Law School and the separate law school for blacks. The Univ of TX Law school had 16 full-time and 3 part-time professors while the separate law school had only 5 full-time professors. In addition, the Univ of TX Law School had 850 students and a law library of 65,000 volumes, while the separate school had 23 students and a library of 16,500 volumes. McLaurin v OK State Board of Regents for Higher Education (1950) – discrimination McLaurin was a companion case to Sweatt v. Painter, which defined the separate but equal standard in graduate education in such a way as to be unattainable. George W . McLaurin was an Af Am OK citizen. Hoping to earn a doctorate in education, he applied for admission to graduate study at OK's all-white university at Norman. Initially denied admission on the basis of race, McLaurin was ordered admitted by a federal district court. Because OK law required that graduate instruction must be “upon a segregated basis,” McLaurin found himself enshrouded in the equivalent of a plastic bubble: in class, he sat in a separate row “reserved for Negroes”; in the library he studied at a separate desk; in the cafeteria he ate at a separate table. McLaurin sought relief from these measures by returning to the district court, and eventually appealing to the Sup Ct. The case was argued and decided simultaneously with the Sweatt case. In a brief and blunt ruling, the unanimous Sup Ct finding ordered an end to McLaurin's separate treatment. Such practices, justices observed, denied McLaurin “his personal and present rights to the equal protection of the laws” as required by the 14 th Amend; McLaurin “must receive the same treatment … as students of other races” Dennis et al. v. US (1951) – freedom of speech The case dealt with citizens' rights under the First Amendment to the Constitution. Eugene Dennis, General Secretary of the Communist Party, USA, was indicted for teaching, conspiring and organizing for the willful overthrow and destruction of the US gov by force and violence, under provisions of the Smith Act. In a 6-2 decision the Sup Ct on June 4, 1951, Ct ruled against Dennis. The court’s decision upheld the Smith Act (1940), citing the precedent set by Schenk v US and the concept of "clear and present danger" as a means of legally limiting free speech. Youngstown Sheet and Tube v Sawyer (1952) – Presidential powers The case arose from a labor dispute between Am steel companies and their employees over the terms of a collective bargaining agreement under negotiation in 1951. Employees wanted higher wages, but management protested that increases could only be met through drastic price hikes. Pres Truman opposed price hikes because the economy was already suffering from inflation. Truman also feared any disruption in domestic steel production would impede US war efforts in Korea and imperil the safety of military troops. In April 1952, Truman ordered seizure of the steel mills in order to forestall a strike which, he claimed, would seriously harm the nation. Although the Taft-Hartley Act gave the pres power to impose an eighty-day "cooling off" period when a strike was threatened, Truman refused to use the law, since he had opposed its passage in the first place. He also chose not to ask Cong for special legislation. Instead, he decided to take control of the companies under his emergency war powers as commander-in-chief. The steel companies did not deny the gov could take control in emergencies. Rather, they claimed the wrong branch of the gov had proceeded against them; in essence, they sued the pres on behalf of Cong on the basis that presidential action violated the constitutional doctrine of separation of powers. The Sup Ct found Truman had not acted pursuant to congressional authority. Prior to issuing the order, Truman gave Cong formal notice of the impending seizure. Neither house responded. The Ct also observed Cong had considered amending Taft-Hartley, to include a provision authorizing the seizure of steel mills in times of national crisis but rejected the idea. Furthermore, there was no other federal statutory authority from which presidential power to seize a private business could be implied. The Ct then addressed the pres's constitutional powers. Article II of the Const delegated certain enumerated powers to the executive branch. Unlike Article I, which gave Cong a broad grant of authority to make all laws "necessary and proper" in exercising its legislative function, Article II limited the authority of the executive branch to narrowly specified powers. The Court held (consistent with Article II) a pres may recommend enactment of a particular bill, veto objectionable legislation, and "faithfully execute" laws passed by both houses of Cong. As commander in chief, the pres was vested with ultimate responsibility for the nation's armed forces. However, the Ct emphasized, the pres had no constitutional authority outside the language contained within the Const. From a constitutional standpoint, Youngstown remains one of the "great" modern cases, in that it helped to redress balance of power among the three branches of gov, a balance severely distorted by enormous growth of the executive branch and its powers first during the Depression, then during the war and the subsequent postwar search for global security. Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954) - segregation and schools Linda Brown was denied admission to her local elementary school in Topeka because she was black. At the time, schools approached equality in terms of buildings, curricula, qualifications, and teacher salaries. Combined with several other cases, including Briggs v Elliott and Davis v County School Board of Prince Edward County Brown’s suit reached the Sup Ct. In a unanimous opinion issued by recently appointed Chief Justice Earl W arren, the Sup Ct broke with long tradition and overruled the “separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Ferguson, holding that despite equalization of schools by "objective" factors, intangible issues fostered and maintained inequality and racial segregation in public education and had a detrimental effect on minority children because it was interpreted as a sign of inferiority. In short, separate but equal was inherently unequal in the context of public education. Responding to legal and sociological arguments presented by NAACP lawyers led by Thurgood Marshall, the Ct stressed the “badge of inferiority” stamped on minority children by segregation hindered full development no matter how “equal” physical facilities might be.