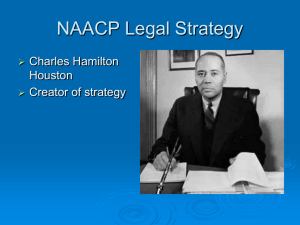

The NAACP legal strategy

advertisement

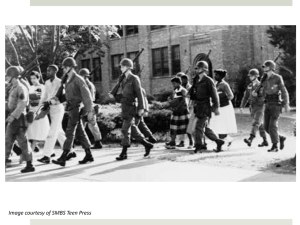

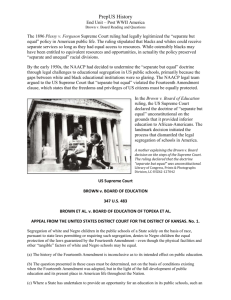

The NAACP legal strategy – lecture notes Beginning in the 1920s, Howard University is transformed into a premier center for civil rights law under direction of Charles Hamilton Houston. The non-profit Garland Fund gives $100,000 to NAACP to “carry out a large-scale, widespread, dramatic campaign to give the Southern Negro his constitutional rights, his political and civil equality, and therewith a self-consciousness and self-respect which would inevitably tend to effect a revolution in the economic life of the country.” Nathan Margold is hired to frame NAACP legal strategy; he argues that NAACP should focus on cases where states provided no facilities for blacks or where it would be difficult, if not impossible, for states to make segregated facilities equal. Failure to equalize segregated facilities would deprive states of constitutional protection under the separate-but-equal doctrine set forth in Plessy v. Ferguson. As chief counsel for NAACP, Charles Hamilton Houston proposes attacking segregation where it is most vulnerable – in publicly funded graduate schools of border states. If the graduate schools can be peacefully desegregated, the NAACP will turn its attention to lower levels of the educational system. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada (1938). Lloyd Gaines seeks admission to all-white law school at University of Missouri; told to apply to all-black Lincoln University, which did not have a law program, or to attend an out-of-state law school at state expense. Supreme Court rules in favor of Gaines, saying states have an obligation to provide equal education to all citizens, regardless of race. Southern states consider setting up regional graduate and professional schools for blacks only, but plans never materialize. Sweatt v. Painter (1950). Herman Sweatt applies for admission to law school at University of Texas at Austin; school complies by renting a room in Houston, hiring two black lawyers as teachers, and calling it Prairie View Law School. Sweatt refuses to attend. Supreme Court rules in favor of Sweatt, orders restrictions removed. McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents for Higher Education (1950). George McLaurin is denied admission to University of Oklahoma graduate school of education. A federal district court judge orders school to provide McLaurin with an equal education; school complies by allowing McLaurin to take same classes as white students “but on a segregated basis.” Case isolates issue of segregation from issue of equalization. NAACP concedes that school has provided McLaurin with equal facilities, but argues that stateimposed segregation stigmatized McLaurin on basis of race and deprived him of an equal educational experience. Supreme Court rules in favor of McLaurin, orders restrictions removed. Victories in Sweatt and McLaurin cases persuade NAACP Legal Defense Fund, led by Thurgood Marshall, to challenge constitutionality of separate-but-equal doctrine head-on. To make case that segregated schools were inherently unequal and that segregation conferred a “badge of inferiority” on black students, the NAACP introduced social scientific evidence. Kenneth Clark, a black psychologist, had devised a test using black and white dolls to measure the damage to black self-esteem caused by segregation. Most black children he tested in the South identified the black doll as inferior and said they liked the white doll better. In 1952, when the Supreme Court agrees to hear six segregation cases lumped together under Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas, there is no clear consensus for overturning Plessy. The death of Chief Justice Vinson and the appointment of Earl Warren to replace him turns the tide in favor a unanimous decision. On May 17, 1954, the Supreme Court announces its decision: “We conclude that in the field of public education, the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal.” The court does not say how it will enforce the ruling; instead, it invites all parties to submit briefs on how the ruling might be put into practice. On May 31, 1955, in a ruling known as Brown II, the Supreme Court orders local school boards to devise desegregation plans “with all deliberate speed,” granting federal district court judges wide latitude in deciding how fast was fast enough. In Virginia, the Byrd machine rallies Democratic Party opposition to desegregation under the banner of states’ rights. The Gray Commission, a state advisory panel appointed to study the implications of the Supreme Court ruling, recommends a series of measures designed to circumvent the order. In 1956, The Virginia General Assembly passes a package of “massive resistance” laws, including one provision to cut off state funding to any school that desegregates and another giving the Governor power to close any public school faced with an order to desegregate. Public schools are shut down in three Virginia cities (including Charlottesville) before the school-closing laws are invalidated by the Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals and a panel of federal judges in 1959. In 1956, James J. Kilpatrick, editor of the Richmond News-Leader, incorporates the nullification theory of John C. Calhoun into an updated states’ rights doctrine called “interposition.” The doctrine holds that a state has the right to “interpose” its sovereignty between the federal government and the people of the state if the people do not agree with the actions of the federal government. In effect, interposition would allow a state to nullify the power of the federal government until the states agreed to a constitutional amendment explicitly granting the power in question. By the end of 1956, five Southern states had passed interposition resolutions, though none invoked it. The cry of states’ rights finds its most militant expression in the Southern Manifesto, a declaration signed by nineteen southern senators and eighty-one representatives of Southern states. Issued in March 1956, the manifesto accuses the Supreme Court of substituting “naked power for established law.” It warns that the decision will destroy “the amicable relations between the white and the Negro races that have been created through ninety years of patience by the good people of both races.”