The Democratic Accountability of Business Improvement Districts

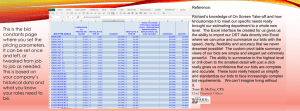

advertisement