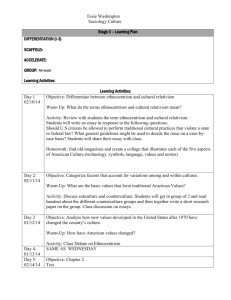

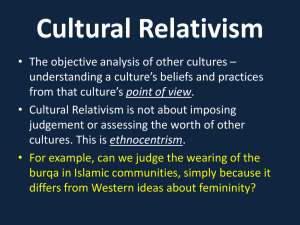

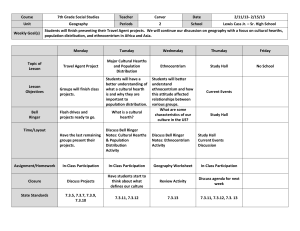

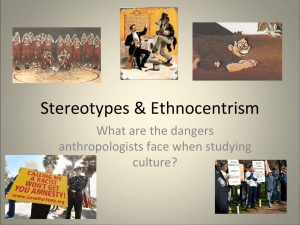

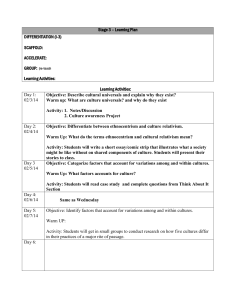

What's Wrong with Ethnocentrism?

advertisement