ethnocentrism and emancipatory ir theory

advertisement

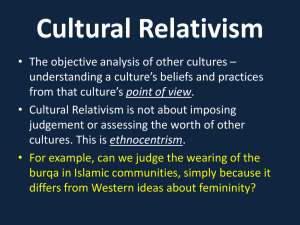

Chapter One ETHNOCENTRISM AND EMANCIPATORY IR THEORY* Amitav Acharya IR Theory as Alienation " I have been a st]-alzgei-irz a strange larzd" Bible, Exodus, 2:22; also found in Sophocles in Oedipus at Colonus " I , a str-a~zgerand a$-aid Irz a world I never- made" A.E. Houseman, Last Poenzs The first encounter of a culturally self-conscious non-Westerner with IR theory may be best captured in the Biblical (an ironic source for the purpose of this chapter) concept of alienation. Alienation hiis something to do with feeling estranged or lackina a sense of belonging. It results from many B sources. For Durkheim, allenation was rooted in -:he weakening of one's societal and religious tradition. Marx saw alienation as the product of the separation of the worker from the means of production. Freud viewed it as the effect of a separation between the conscious slid unconscious parts of mind. More generally, a random internet search of the concept produced the following definition: "estrangement from other people, society, or world, 'a blocking or dissociation of a person's fzelings' produced by a shallow and depersonalized society."' In IR theory, I argue, alienation afflicts those who find the great debates and theoretical breakthroughs of IR taking place with complete disregard for the totality of world culture and experience - especially of their own. The discipline called International Relations has seen endless contestations and compromises involving one school deconst~ucting,exposing, and seeking to overcome the imperfections, dominations, and exclusions of another. The early debates were known as 'inter-paradigmatic,' and pitted * 1 This chapter owes its inspiration to discussions in the IR Core Course in the Political Science Department at York University during the Fall of 1997. It owes a deep intellectual debt to the students in the course: 1-yler Amood, Gi Bin Hong, Matina Ka~ellas,Rodn?y Loeppky, Massoud Moin, and Deniz Roman. I remain solely responsible for the views expressed. Encarfa Online Concise Encyclopedia, http://encarta.rnsn.corn. the Idealists against the Realists, the behaviouralists against classical approachists, and pluralists against structuralists. More recent debates have been less grandiose, but equally vicious: between neo-liberals and neorealists over relative gains; between rationalists and constructivists over identity and interests; between positivists and post-positivists on epistemology and ontology. Whatever the outcomes of these debates and their implications for IR theory-building, one thing is missing from the picture: a concern with the persisting ethnocentrism of the field and the willingness of theorists to deal with it beyond a most superficial sort of acknowledgement. The aim of this chapter, written from the perspective of someone who has become more interested in IR theory after overcoming a great deal of initial reluctance, is not to start a new debate, and certainly not another inter-paradigm debate. Rather, the chapter's intent is to underscore this critical flaw in the discipline, and urge on the view that the theoretical debates in IR should not just be about a 'search for thinking space,' but also about overcoming alienation. IR Theory, Social Anthropology, and the Problem of Centrism Among the social science disciplines, anthropologists have a particular fascination with centrism. Contemporary IR theorists might see their own field as more glamorous, dealing with peace, power, and hegemony, while anthropologists are left to deal with 'primitive cultures.' But, IR theory lags behind Anthropology in acknowledging its centrism. Levi-Strauss's critique of the category 'barbarian' has no equivalent in Intelnational Relations. The subject of ethnocentrism does not figure in the interparadigm debate, and it is a measure of the extent of the issue's neglect that there has been only one really serious scholarly attempt to examine the phenomenon in International Relations, Ken Booth's Strategy a n d Ethi~oce~ztl-ism, published in 1979.' While the problem of ethnocentrism in IR is similar to that in Anthropology or Sociology (indeed, Ken Booth's pioneering study borrowed definitions from these fields), there is an important element which is special to IR. The anthropologist's definition of ethnocentrism is non-exclusionary. If anything, an anthropologist, no matter how ethnocentric he/she may be. will not be influenced by it to the extent that he/she will simply ignore phenomena that do not conform to hisher mental framework. Indeed, the business of anthropologists is to investigate any unusual phenomena; 'primitive societies or societies that are culturally different from one's own are studied with great interest precisely because of that commitment. In IR, howeyer, such curiosity is noticeably lacking. Therefore ethnocentrism in IR takes on an added dimension. In'IR, ethnocentrism creates the basis for exclusion and ignorance. 7 2 Ken Booth, Strategy and Ethnocentrism (London: Croom Helm, 1979). All forms of centrism require the creation of the notion of the outside. As a social practice, ethnocentrism starts with the marking off of others as nonmembers. It is produced and reproduced by the dcnial of the identity of others. Ethnocentrism is closely llnked to territoi-iality, defined by The Social Scie~zceE~zcyclopediaas "bounded spaces ir:. the exercise of power and influence" which indicates a "differential access to people and things."" To understand the multiple dimensions of ethnocentrism, w e turn to the following sources: The Dictio17a1-)% ofAnthr-opology:"universal tendenc). to judge or interpret other cultures according to the criteria of one's own ~ u l t u r e . " ~ I~ztel-~zational Encyclopedia of the Social Scielzces: "attitude that 'one's way of life is to be preferred to all others."15 Macnzillarz Dictionary of Alzthr-opology:"the habit or tendency to judge or interpret other cultures according to the criteria of one's own ~ u l t u r e . " ~ The Macnzilla~z Stziderzt E~zcyclopedia of Sociologv: "the tendency to evaluate matters by reference to the values shared in the subject's own ethnic group as if that group were the centre of e~erything."~ The Cor~ciseOxford Dictionary of Sociology: "the practice of studying and making judgments about other societies in tenns of one's own cultural assumptions or bias. Ethnocentrism often suggests that the way something is done in other societies is inferior to t:le way it is done in one's own s o c i e t ~ . " ~ Ken Booth (Strategy arzd Ethnoce1zt1-isnz):the inabil [ty to "see the world through the eyes of a different national or ethnic group: it is the inability to put aside one's own cultural attitudes and imaginatively recreate the world from the perspective of those belonging to a different group."9 Ken Booth identifies three meanings of ethnocentrism: (1) as a term to describe feelings of group centrality and superior it:^; (2) as a technical term to describe faulty methodology in social sciences; and, (3) as a synonym for being "culture-bound."lo Adam Kuper and Jessica Kuper, eds., The Social Science Encyclopeclia, 2nd ed. (London: Routledge, 1996). 4 Thomas Barfield, ed., The Dictionary of Anthropology (Cambridge: Blzckwell, 1997). 5 David Bidney, "Culture," in David Sills, ed., International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences, vo1.3 (London: Macrnillan Company and the Free Press, 1968), p.546. 6 Charlotte Seymour-Smith, ed., Macmillan Dictionary of Anthropology (London: Macmillan Reference Books, 1986), p.97. 7 Michael Mann, ed., The Macmillan Student Encyclopedia of Sociology (London: Macmillan, 1983). 8 Gordon Marshall, ed., The Concise Oxford Dictionary of Sociology (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1994), p.158. 9 Booth, op. cit., p.15. 10 Ibid. 3 Ethnocentrism in IR presents itself in many forms and dimensions. I will list three main forms here, and these are closely related. The first, and perhaps most commonplace tendency, is to simply ignore the non-Western other. It means not bothering to know about the experience of the other. In a chapter entitled "Theory of World Politics" in his 1989 book, Inter-izatiorzal Zr?stitz~tiorzsarzd State Power-,Robert Keohane, a leading IR theorist, penned the following confession: An unfortunate limitation of this chapter is that its scope is restricted to work published in English, principally in the United States. I recognize that this reflects the Americanocentrism of scholarship in the United States, and I regret it. But I am not sufficiently well-read in works published elsewhere ro comment intelligently on them." In acknowledging his limitations, Keohane pointed to the "distinctively American stamp that has been placed on the international relations field." Other examples of ethnocentrism abound and are not the least bit confined to mainstream theories such as neo-realism and neo-liberalism. It should surprise no one familiar with the discipline that one of the most influential books on multilateralism to emerge in recent years, edited by John Ruggie, does not contain a single chapter dealing with multilateralism in the Third World (NATO and CSCE are duly accounted for, however) or between the exclusion of the non-West is equally North and the South.1-e pronounced in Security Studies, as Security Studies as a discipline developed primarily as a study of American national security and the 'central East-West strategic balance' with scant attention to regional security issues in the Third World.13 The celebration of the Cold War as a 'long peace,' rooted in Waltz's neorealist assertion that bipolar international systems are more 'stable' than multipolar ones, takes us to another level of blindness.14 Such generalizations may seem particularly absurd to those with a modicum of sympathy for the victims of Korea, Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iran-Iraq, and the India-Pakistani conflicts, not to mention the victims themselves. While Keohane at least provided an honest acknowledgement, most other theorists, including many of the post-modem, post-structuralist critics of 11 Robert Keohane, "Theory of World Politics: Structural Realism and Beyond," in Robert 0 . Keohane, ed., lnternational Institutions and State Powec Essays in lnternational Relations Theory (Boulder: Westview Press. 1989), n.1, p.67. 12 John Gerard Ruggie, Multilateralism Matters: The Theory and Praxis of An Institutional Form (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993). 13 Amitav Acharya, "The Periphery as the Core: The Third World and Security Studies," in Keith Krause and Michael Williams, eds., Critical Security Studies: Concepts and Cases (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), pp.299-327. 14 On the 'long peace' argument, see John Lewis Gaddis, "The Long Peace: Elements of Stability in the Post-War lnternational System," lnternational Security. 10:4 (Spring 1986); On the 'stability' of bipolarity, see, Kenneth N. Waltz, "The Stability of the Bipolar World," Daedalus, 93:3 (1964), and Kenneth Waltz, Theory of lnternational Politics (Reading: Addison Wesley, 1979). 'mainstream' scholars llke Keohane, simply do not bother with confessions, even as they celebrate dissidence in IR theory and claim to engage in developing an emancipatory discourse that would liberate and empower the marginalised scholars of the discipline. A second manifestation of ethnocentrism in IR is the tendency to view world politics from the prism of one's own national 01. 'bloc' experience and perspective, or what anthropologists may see as "the tendency to assess other cultures in terms of one's own culture." One ol' the clearest examples of this tendency can be found in the treatment of Third World conflicts in Cold War Security Studies. Consider the following. observation on these conflicts, made not by an IR scholar, but by a trainc:d anthropologist who certainly has the ability to recognise ethnocentrism when he sees it: In discussions of collective violence and security in he Third World, the local-level concerns that motivate less powerful nations and local groups tend to fall from view. Instead, a privileged position is accorded to the interests and interpretations of the superpowers, and diplomatic and military initiatives are treated from the perspeclive of ideological, political, and economic superpower contests.15 Analysing a well-known Rand Corporation study O F U.S. involvement in Third World conflicts,16the writer found that American involvement in the Third World was considered "almost entirely from the perspective of military concerns." Moreover, the study treated rhe U.S. involvement "primarily in relation to the Soviet Union, for the rnost part ignoring the specific interests and concerns of Third World countries and groups." The writer concludes that this study was characterized by a "preoccupation with East-West relations, to the exclusion of numerous regional concerns around the world."'7 Such modes of thinlung and analysis would be forgiven had they been innocent and inconsequential, and had they not contrj buted to greater levels of violence in the Third World. The refusal of Vrestern strategists and policy-makers to recognize regional conflicts in the 'fiird World except as a 'side-show' to the great game of the superpowers ensured not only grave distortions in the understanding of the causes artd remedies of these conflicts, but might also have had the more pemiciclus effect of rendering these struggles more 'permissible.'l8 15 Robert Rubinstein, "Collective Violence and Common Security," ir Tim Ingold, ed., Companion Encyclopedia to Anthropology (London: Routledge, 1994), pp.983-100,3. 16 Stephen Hosmer, Constraints on U.S. Strategy in Third World Conflicts (Santa Monica: Rand Corporation, 1985). 17 Rubinstein, op. cit. 18 On the 'permissibility' of Third World conflicts and their role as a way of ',letting off steam" in superpower tensions, see: Mohammed Ayoob, "Regional Security and the Third World," in Mohammed Ayoob, ed., Regional Secur~tyin the Third World (London: Croom Helm, 1986). 6 Acharya Being theoretical in IR not only means to contest and compromise, but also to condescend. Thus, a t h d form of the ethnocentrism afflicting the field is the tendency to view the non-West's experiences as 'inferior.' Remember Robert Gilpin's assertion that free trade is imposed by a "superior society."l9 This assertion formed a key basis of the hegemonic stability theory according to which a hegemon - a Western hegemon to be sure - is needed to provide collective goods for the whole of manlund, including the uncivilized people of the Third World who may not recognize the benefits of 'free trade' because of their dependence on Western economies. To be sure, nobody has gone so far as to label Third World practices as 'barbarian' or 'primitive.' Yet, IR equivalents of these anthropological categories do exist. The most famous project to study war, the 'Correlates of War' project at the University of Michigan, led by Singer and Small, used criteria for defining war which excluded imperial and colonial wars because of the "inadequate political status of their participants." As a consequence, while the project's data set for interstate wars from 1816 to the then-present (1972) involving "nation-states" was definitive, the data for "extra-systemic" wars - i.e., imperial and colonial wars - remained, as Vasquez observes, "woefully incomplete for non-national entities...usually the victims in this historical period." Vasquez concludes: The discrepancy in the quality of these data sets may be seen as part of the historical legacy of Western imperialism and racism that simply did not regard non-Western groups as civilized or as human beings equal to whites. It is not unfair to assume that such attitudes played some role in accounting for the fact that Western nations did not bother to record in any systematic way the fatalities sustained by non-national groupings in imperial wars of conquest or pacification.20 The tendency among deterrence theorists to insist on 'rationality' as a precondition for the applicability of their theoretical constructs goes with another crucial assumption: that Third World leaders are unfit to possess such weapons. This view is held not just by many Western nuclear strategists, but as Hugh Gusterson's ethnog-aphic study of Lawrence Livermore Laboratory confirms, by American nuclear scientists and weapon designers as well." The criteria of rationality also separate the more contemporary 'rogue states' from those, presumably civilized and trustworthy, owners of the weapons of mass destruction. IR theorists concerned with rationality deny the possibility that nuclear weapons can be safely acquired and managed by Third World countries. K. Subhramanyam, an Lndian strategist, has called this tendency "racist.'c' 19 Robert Gilpin, War and Change in World Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1981), p.129, cited in Isabelle Grunberg, "Exploring the Myth of Hegemonic Stability," International Organization, 44:4 (Autumn 1990), p.447; For a critique of the ethnocentric bias of the hegemonic stability theory, see: Grunberg, pp.444-448. 20 John Vasquez, The War Puzzle (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), p.27. 21 Hugh Gusterson, "Nuclear Weapons and the Other in the Western Imagination," Cultural Anthropology, 14:1, pp.lll-143. 22 K. Subhramanyam, "Export Controls and the North-South Controversy," Washington Quarterly (Spring 1393). Ethnocentrism and Emancipatory IR Theory 7 Explaining Ethnocentrism: The Foundational Myths, the 'Columbus Syndrome,' and the Production of Knowledge The very idea of theory in IR contributes to ethnocentrism. Theory after all is a search for coherence; a narrower ontology obviously serves the ends of theory. The search for theoretical coherence often outweighs the quest for emancipation and cosmopolitanism. And the two may be antithetical. "If coherence within international relations is finally a product of AngloAmerican nurturing, disciplinary and cosmopolitan ideals may never be reali~ed."'~ Beyond this, there are other factors, having to do with power, the 'Columbus Syndrome,' foundational myths, and the process of going theoretical for the non-Westerner. Tlze Distl-ibutiolz of Power. and tlze PI-oductioi?of Knowledge Writing a review of the development of the field since it was "founded" by David Davies, "a wealthy Liberal MP in Wales," Ken Booth wondered: "what ...would the subject look like today...if the subject's origins had derived from the life and work of an admirable black, feminist, medic, shechief of the Z U ~ U S The . " ~ very ~ fact that Booth is one of the very few among IR's leading lights to even contemplate this question is in itself an indication of the extent of the problem. The questions he raises are interesting, but the conclusion he reaches is disheartening. The fact that the field of IR was founded by David Davies rather than the Zulu chief is, going by Booth's perspective, no accident, because it reflected, and continues to reflect, the correlation between the distribution of power and production of knowledge in the contemporary world order. In this world, it is the materially powerful that dictate the terms of theory-building. I have a slight disagreement with Booth. The issue is not that there has been no IR theory which is'derived from the experience of admirable or not so admirable natives of the non-West. The fact is that there have always been places in the world where what may be considered 'international relations,' or the 'affairs of the world at large' have always been seen and conceived in terms markedly different from those underlying Western scholarship. The apparently inscrutable Brahmins, and the profoundly self-centric Chinese. can claim as interesting and, from their own vantage-points, 'accurate' theories of world affairs as can Morgenthau, Waltz, and the other Western gurus of IR theory.' But the problem is that only the latter are so recognized. And this may have something to do with the 'Columbus Syndrome. ' 23 William Olson and Nicholas Onuf, "The Growth of a Discipline," in Steve Smith, ed., International Relations: British and American Perspectives (New York: Blackwell, 1985), p.18. 24 Ken Booth, "75 Years On: Rewriting the Subject's Past - Reinventing its Future," in Steve Smith, Ken Booth, and Marysia Zalewski, eds., International Theory: Postivism and Beyond (Cambridge: Camb~.idyeUi~ive~siiy Fress, i3363, p.330. 8 Acharya The 'Colunzbus Sylzdronze' A startling anthropological discovery in a place called Clovis in New Mexico, USA, provides an appropriate backdrop for reflection on the origins of International Relations theory. At Clovis, researchers looking for evidence of the first humans in the New World discovered artifacts that date back 11,000 years. The real significance of this discovery was not the rekindling of the debate about who the first Americans really were. Rather, it was the inception of the "Clovis police," described by the Ecorzonzist as "those who attempt to stamp out the heretical idea that mankind is long established in the Americas," well before "fourteen hundred and ninety two, [when] Columbus sailed the ocean blue."'5 For an IR scholar fed up with the refusal of the discipline to acknowledge the ideas and contributions of non-Western sources of international thought, the debate about the identity of the first Americans is akin to the question 'who were the first theorists?' I am not indicting Western scholars of International Relations, especially those who call themselves theorists, as variants of the Clovis police, out to trample on any notion that International Relations theory might have originated outside of the Anglo-Saxon world. Yet, there is a discomforting similarity between the Clovis police and the community of IR scholars who rule the discipline through their ideas and instruments (such as journals, editorship of prestigious monograph series, and positions which enable them to recruit students and provide grants). While International Relations may no longer be regarded as an 'American social science' (though it very much remains a 'Western social science'), the theoretical literature provides scant recognition and regard for theorists and theoretical insights from non-Western backgrounds. While the introduc~oryhistorical chapters of many textbooks on IR, dealing with the evolution of the international system, may these days include a section on China or India, and a few quotes from Kautilya or Confucius or Sun Tzu, this recognition of non-Western contributions stops as one moves to the discussion of more contemporary issues such as power, interdependence, and hegemony. Here, the overwhelming majority of theorists are Western, mostly American. It is as if, when it comes to International Relations, nothing of substance or significance has ever been said by anyone who grew up in Calcutta or Ulan Bator, Jakarta or Nairobi. There are exceptions to be sure, and references to Gandhi in sections dealing with peace studies, or to Fanon in discourses on dependency may be found. But, the implicit message seems to be that without Western theorists and the Western experience, we would not have a discipline of International Relations. 25 'The First Americans," The Economist, 21 February 1998, p.79. Ethnocentrism and Emancipatory IR Theory 9 Fo~lrzdatioizalMytlzs This is by no means a novel complaint. International theorists sometimes do recognize problems of ethnocentrism and occasionally lament it, but seldom do they try to overcome it in their own writings. Banal and objectionable as these examples may be, ethnocentrism in IR is hardly surprising. We have a discipline whose foundational myth dates the origins of the 'modem international system,' hence the source of much theorizing about international relations, to the magical year of 1648, the Peace of Westphalia. We are constantly reminded that the modem international system is the European states-system writ large, that the world we live in today consists of nothing other than the expansion and universalization of European international society. Yet, can 1648 mark the beginning of international relations any more than 1492 represents the 'discovery' of America by Christopher Columbus? For someone who grew up in the villages and towns of India, Indonesia, or China, the predominance of Thucydides, Machiavelli, Morgenthau, Kant, Gramsci, and Foucault in the writings of a field whose scope is supposed to encompass herlhis own native land must be profoundly alienating. Moreover, as Morgenthau and Thomson put it in 1954, "the subject matter of international politics is struggle for power among sovereign nations."'6 If this be so, then those countries which are yet to be sovereign, or are barely sovereign, or have had too little power to matter in the "struggle for power among sovereign nations" are naturally to be regarded as the objects, rather than the subject-matter of IR. Their struggles are often left for the students of Comparative Politics to analyze and study - while IR focuses on the more profound and consequential matters involving the West. Similarly, the supposedly foundational concepts of IR, such as anarchy and sovereignty, deny the possibility that political communities might have existed in the past, and may continue to exist in parts of the world, that do not resemble the Westphalian state. Goiizg Theol-etical:A Treaclzei-ous Jourizey Theo~yin International Relations serves many ends. For rationalists, it is about explaining and predicting state behaviour and international events. For critical theorists, the purpose of theory is to uncover domination. For anti-positivists, theory is about searching for 'thinking space.' But theory can also be about discovery of self. The project of going theoretical is about a journey in self-discovery. A student of International Relations in Ravenshaw College, Orissa is likely to know very little about the inter-paradigm debate. He or she is even less likely to have heard about French post-structuralism or Western post- 26 Cited in Olson and Onuf, op. cit., p.5. 10 Acharya modernism. He or she is more likely to have read the worldviews of Gandhi or Nehru than Foucault. Yet International Relations theory claims to represent us all. In elaboration, I return to, and repeat, my initial focus on alienation. Alienation occurs when one stands outside of the lore of the discipline, unable to comprehend or even relate to its foundational myths. Alienation sets in when one's own conceptions of how the world is conceived, organized, and managed finds no place in the prevailing orthodoxy of IR o r among those who seek to challenge it. Alienation occurs when one is asked to view the world through a Waltzian, Gramscian, or Foucaldian prism instead of a Gandhian or Fanonian one. When alienation grows, disorientation sets in. Facing alienation, one course of action is to turn oneself into an intellectual anarchist, rejecting everything, as long as this turn does not compromise one's grades. This is a short step to embracing area studies, studying events and trends about one's country or region of origin. Another way is to jump wholeheartedly into the source of alienation and take in the ancient wisdom of alien lands as quickly and in as short a time as possible, for theory is not just a requirement for survival, it is also a source of status. Without theory, one is likely to be ridiculed and isolated in one's own academic environment. Unfamiliarity with Waltz, Keohane, or Foucault is a deadly sin which will not only spoil social evenings at graduate parties, but sink career hopes, as well. But deciding to be theoretical is not enough. One has to be 'correct' in one's theoretical predisposition. Going theoretical is an act of political choice. One may hope that there is something natural about why one chooses a particular theory. But in reality, this is rarely the case, I suspect. Theory, like fashion, is generation- and time-specific. It is also spacebound. Theory is chosen not because it appeals to one's natural instincts, but because it best fits one's social and material circumstances. Going theoretical is by itself hardly an act of emancipation. One must be aware of two countervailing tendencies: devotion and aversion. Devotion applies both to the 'gatekeepers' and the 'gatecrashers' (to be discussed below). Despite all this lip-service to methodological pluralism, the 'gatecrashers' of the discipline remain as much devoted to their respective and peculiar epistemological, methodological, and linguistic pastures as the so-called 'gatekeepers.' A second and related tendency is aversion. The target of aversion is not only the atheoretical - or anti-theoretical - type but also the theory-minded from a rival school. The so-called honest intellectual debate between 'gatekeepers' and 'gatecrashers' is more often likely to be a fatal shootout aimed at destroying peace of mind and sometimes careers. IR theorists are among the worst hypocrites when it Ethnocentrism and Ernancipatory IR Theory 11 comes to honouring the self-professed commitment to keep intellectual animosities separate from personal ones. The two are closely linked. 'Gatekeepers' and 'Gatecrasher-s' If the high priests of Realism and liberalism are to be called the 'doorkeepers' or 'gatekeepers' of the discipline, then those who question their authority and orthodoxy may be called 'gatecrashers.' The 'gatecrashers' are a diverse lot, but share one thing in common: resistance to exclusion and a commitment to emancipation. But the metatheoretical debates and preoccupations of IR scholars devote so much time and energy to fighting exclusion that they have tended to neglect the issue of emancipation. For example, the concept of national security has been attacked mercilessly for its exclusionary bias; yet few pause to ask whether broadening the scope of security discourse to cover environment, migration, and drugs is an emancipatory act in itself. Security and emancipation do not mix well. Securitizing non-military, non-war phenomena is merely a way of restricting discourse and finding new ways of domination. By emancipatory theory, I mean theories that not only seek to expand the horizons of IR, and resist exclusion of certain social groups (e.g., women) and issues (e.g., the environment), but also those which resist all forms of centrism, including ethnocentrism. Moreover, the aversion of the 'gatecrashers' to anything remotely resembling policy has the unfortunate consequence of engendering a lack of interest in advancing the cause of emancipation. An emancipatory theory of IR, in my view, must go beyond a critique of epistemological and methodological assumptions of conventional IR theory and establish its claim to praxis. The real debates about IR theory should not just, or primarily, be about 'thinking space,' but about strategies and agendas that promote a transformation of world order. What is the record of the 'gatecrashers' with respect to ethnocentrism? Let us look at four major bodies of work, recognizing, however, an element of overlap between these categories. 1. The Third World PI-edicai7zerzt. One category of work seeks to establish how IR concepts, for example those involving security or foreign policy, derived largely from the West do not fit the non-West. Such work is not necessarily based on assertions about cultural uniqueness of the Third World. Rather, this body of literature, with major contributions from Mohammed Ayoob and Barry Buzan, identifies a specific Third World 'predicament,' in which the security concerns of states and regimes focus not so much on protection of sovereignty and territorial integrity from external threats, but on the preservation of regime security and political stability from internal threats. Another aspect of this category of work has 12 Acharya been the attempt to build models of foreign policy and security that fit the conditions of the Third World. As the Cold War drew to a close, this body of literature did make a significant contribution in addressing the ethnocentrism of Security Studies, especially in the sense of the neglect of the non-West and developing conceptual tools for security analysis from the experience of the non-West, instead of simply using standard Western categories. On the other hand, such writings do tend toward over-generalization, given the problematic nature of the very notion of a 'Third World' even before the end of the Cold War. Not only are the various constituents of the Third World, or South, too diverse to permit definitive generalizations about a common security predicament, but the distinction between the First World and the Third World can be rather arbitrary, since social and political conditions that constitute the more recent notion of 'human security' exist everywhere, even in the West. Neither is the specification of a Third World security predicament necessarily emancipatory. 'Subaltern Realism,' a-term coined by Mohammed Ayoob, is a relevant example here.27 Subaltern Realism in Security Studies seeks to incorporate the security concerns of "the weak and of inferior rank." But its emancipatory claims may be limited by its focus on the security of the Westphalian state.28 2. U~ziver.salIrztel-natio~~al S o c i e ~ This . body of literature revolves around the important claim that many of the so-called 'modem' and supposedly Western concepts of IR, such as the state, balance of power, hegemony, anarchy, and so on, predate Westphalia and transcend Europe. It assumes of the universality of international society. Adam Watson's The El~olutior~ I~ztel-rzatio~zal Society best exemplifies this type of work.29 There is an element of irony here, since Watson belongs to a theoretical tradition labeled as the 'English School,' one of whose key figures, the late Hedley Bull, did more than most to popularize the apparently uncomplicated view that it was the European state-system that enlarged itself into a "universal international society" in the process of colonialism and decolonization.30 He did so by looking into the Westphalian norms of sovereignty and territorial integrity, with little attention to the pre-colonial political concepts that might have persisted and worked to severely distort the Westphalian overlay so as to deny the possibility of a universal international system. 27 Mohamed Ayoob, "Defining Security: A Subaltern Realist Perspective," in Keith Krause and Michael Williams, eds., Critical Security Studies: Concepts and Cases (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1997), pp.121-146. 28 Tyler Attwood, "Security Studies and the Third World," unpublished paper, York University, Department of Political Science, Fall 1997, pp.3-5; Massoud Moin, "Redefining Security and the Inter-Paradigm Debate," unpublished paper, York University, Department of Political Science, Fall 1997, p.2. 29 Adam Watson, The Evolution of lnternational Society: A Comparative Historical Analysis (London: Routledge, 1992). 30 See Bull's contributions in Hedley Bull and Adam Watson, eds., The Expansion of International Societv (Oxtord: Clarendon Press, 1985). Ethnocentrism and Emancipatory IR Theory 13 Nonetheless, what emerges from this literature is significant. If modem international relations was shaped by a struggle between the principles of empire and anarchy in which the latter prevailed, then its roots must be seen to lie not just in the Westphalian settlement, but in the struggles of ancient China (The Warring States) and India (the Maurya era). The Asian experience could thus be seen as throwing up a number of supposedly 'modern' ideas about IR (such as balance of power, sovereignty, and collective security) long before they were evident in the European context. If one goes by this logic, then IR theorists seeking to find alternative political forms to the Westphalian state should consider the period in India under the Mauryas. Those looking for the foundations of the secular conceptions of the state might consider Mauryan Prime Minister Kautilya's argument that the true aim of power is not to please the gods, but to attain the happiness of the state (including its people). Similarly, one of the foundational debates in IR theory, the so-called Realist-liberal debate, ought to begin not from the Wilsonian critique of the European balance of power system, but from the contestation of ideas during the Warring States Period in China which featured a much more powerful and pluralistic debate (both in the intellectual arena and in the battlefield) involving the Dao (anarchic pacifism), Confucian (pro-hegemony based on the concept of the mandate of heaven, but with moral restraints on the ruler's domestic and foreign policy), Mo-zi (anarchic but not pacifist like Dao, pioneered the doctrine of defensive war to counter offensive hegemonism and the concept of armed neutrality), and the Legalists (pro-hegemony with a strong advocacy of offensive military power without the Confucian moral restraint). But a key problem with this work is its underlying assumption that the historical heritage of the non-West can be searched and studied in terms of categories that are derived from the West itself. More often than not, the search for a universal international society degenerates into a search for categories from the abundance of non-Western experience that either parallel or 'pre-replicate' the ideal-types of Western statecraft. As such it offers only a limited challenge to the problem of ethnocentrism in IR theory. Moreover, such work has its own problem of 'centrism'; it is often Indo-, Sino-, or Egypto-centric. The historical experience of Africa and South America has merited little attention. Part of the reason for this may have to do with the focus of such work on instruments of 'statecraft' associated with large and powerful empires. Ironically enough, political and social systems that fell short of enlpirehood do not figure in the search for the historical antecedents of a 'universal international society.' 3. Cr-itical IR Theory. Almost by definition, this is a very broad canvas, which contributes to the vagueness and mystique surrounding the label itself. Critical IR theory includes such diverse threads as Marxism, neoMarxism, Gramscian approaches (Robert Cox is a major figure in these 14 Acharya approaches), feminism (Cynthia Enloe, Christine Sylvester, V. Spike Peterson), and post-modemism (Jim George, Michael Shapiro, R.B.J. Walker, Richard Ashley, James Der Derian). If there is one thing that binds these together, it would be a collective challenge to the dominance of Realist and liberal perspectives on international relations. Take for example, the approaches of critical IR theories to security. Underlying most is a shared view that the state, instead of being a provider of security, can be a threat to people's security. Critical IR theories profess a normative concern with global security as opposed to the security of the nation-state or the inter-state system. They challenge the narrow focus of mainstream Security Studies on issues of war and military force, and resist the exclusion of issues of race, gender, ethnicity, and other forms of identity in the discourse of Security Studies. Post-modern and post-structural theories resort to deconstruction and discourse analysis in order to expose the deliberate construction of national security threats by the ruling elite to maintain regime security and justify military budgets. Critical IR theories take a broad view of security, including the fate of the biosphere and population movements linked to globalization. Multilateralism is a preferred approach to managing insecurity, but this is not the multilateralism among states, but a broader and more inclusive notion of multilateralism involving social movements and civil society. Feminist scholarship has done much to address the problem of ethnocentrism in IR. Not oilly are many of its leading lights and most original thinkers working on the non-West, they are actually from the nonWest. Moreover, feminist perspectives have made important contributions in not only exposing the exclusionary nature of IR theorizing, but also in offering pathways in respect of how this can be overcome. But one should not assume a convergence of views between Western and Third World feminist scholars; the disagreements and conflicts which exist between them in praxis are also reflected in theory. Feminist thinlung and praxis in Botswana do not necessarily fit into the categories and constructs of Western feminist appr0aches.3~ If feminism has done most to address the ethnocentrism of IR theory, postmodernism has probably done the least. To be sure, the very idea of modernity which it contests is profoundly anti-emancipatory to the nonWest. The very fact that the dividing line between modernity and its 'post condition is traced to the Enlightenment is significant here. The achievements of post-modernity are being claimed on the basis of an historically-specific development that is essentially European. Moreover, post-modemist and post-structuralist approaches to IR might have liberated us from the excessive rationalism of the Enlightenment, but they have never 7 31 Alex Mogwe, "Human Rights in Botswana: Feminism, Oppression, and 'Integration'," Alternatives, 19 (1994), pp.189-193. Ethnocentrism and Emancipatory IR Theory 15 come to terms with the fact that many areas of the non-West have been so marginalized in the historical processes of colonialism and neo-colonialism (itself a product of Enlightenment) that for some non-Western states and societies at least, what passes for 'modernity,' including a commitment to illtellectual and policy rationalism, is a legitimate but still-elusive aspiration. Moreover, an argument can be made that in IR theory, the post-modern challenge to ethnocentrism is set by the need to counter the Anglo and Anglo-American with the help of the Franco. Missing from this is the nonWest, the non-Anglo-American and the non-Francophile. When Der Derian uses the term Anglocentrism to characterize Jeremy Bentham's context when he became the first to use the term 'international,' or the "AngloAmerican discipline of international relations," he is concerned with the goal of countering it with "continental philosophical incursions," especially those plotted by neologistic Francofiles.3' But ironically enough, a few of the critics of the post-modern project themselves have fallen into the same trap. Of particular relevance here is postcolonial theory, which seeks to dismantle all binary distinctions between West and the rest, such as that between First World-Third World, North-South, and centre and periphery to "reveal societies globally in the complex heterogeneity and contingency."33 Gayatri Spivak began by challenging Foucault for treating "Europe as a self-enclosed and selfgenerating entity, by neglecting the central role of imperialism in the very making of Europe."34 Edward Said has made similar criticisms, accusing Foucault of neglecting not only European imperialism, but also resistance to imperialism outside of Europe. But postcolonialism cannot be regarded as an authentic attempt to counter ethnocentrism, because postcolonial discourses, as Arif Dirlik points out, are intended "to achieve an authentic globalisation of cultural discourses by the extension globally of the intellectual concerns and orientations originating at the central sites of Euro-American cultural criticism."35 Thus, postcolonialism seeks "not to produce fresh knowledges about what was until recently called the Third World but to re-structure existing bodies of knowledge into the poststructuralist paradigms and to occupy sites of cultural production outside the Euro-American zones by globalising concerns and orientations originating at the central sites of Euro-American cultural production."36 32 James Der Derian, "The Boundaries of Knowledge and Power in International Relations," in James Der Derian and Michael Shapiro, eds., International/lntertextual Relations: Postmodern Readings of World Politics (Lexington: Lexington Books, 1989), pp.7-9. 33 Arif Dirlik, 'The Postcolonial Aura: Third World Criticism in the Age of Global Capitalism," Critical Inquiry (Winter 1994), p.329. 34 Aijaz Ahmad, "Postcolonial Theory and the 'Post'-Condition," in Leo Panitch, ed., Ruthless Criticism of all that Exists, The Socialist Register 1997 (London: Merlin Press, 1997), p.374. 35 Dirlik, op. cit., p.329. 36 Ahmad. op. cit.. p.368. 16 Acharya Gramscian approaches, especially the work of Robert Cox, have made a far more sincere attempt to go beyond their European heritage. Cox's early work on IR theory and his more recent work on civilizations stand out in their attempts to consciously (self-consciously?) draw upon and incorporate the thinking of Ibn Khadun.37 His critique of globalization focuses on the marginalization of labour and destruction of the environment in both the West and the non-West.38 Yet, the Gramscian notion of hegemony as a single overarching framework for analyzing and explaining world events is problematic because of its potential to ignore or marginalize social, cultural, and economic structures and agencies which are locally produced and may not relate well to an historical-materialist explanation based on the dominance of global production processes. For example, one may well explain economic liberalization in India or human rights abuses in China in terms of globally dominant ideas and material structures; but the influence of important local historical and inter-subjective factors could be lost in the process. How much of the latter should inform the former? Within Gramscian perspectives, the non-West exists only as the object, rather than subject, of a hegemonic world order. The thoughts and approaches of the non-West 'local' are conditioned primarily by the ideas and material instruments of the Western and hegemonic 'global.' This runs the risk not only of re-legitimizing the oppressive ethnocentrism of IR theory, but also of marginalizing the emancipatory strategies of the multitude of non-Western voices. The normatively appealing visions of a 'global civil society' promoted by critical theorists, including neoGramscians, which link together social movements around the globe, are a case in point as they blur crucial material and inter-subjective distinctions between the West and the non-West.39 4. Retzir-12of Cz~ltzir-e and Iderztity. The 'return of culture and identity' to IR theory has been the subject of much joy and celebration. It is hardly necessary to revisit the debate regarding the necessity of considering culture and identity questions in IR theory. However, it must be kept in mind that this exclusion had always been more true of Western scholarship than of non-recognized IR scholars in the non-West. A scholar from the non-West was always more llkely to accept culture and identity as the basis of IR discourse, rather than the models and abstractions of problem-solving and critical Western theory. 37 Robert Cox, Approaches to World Order (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1996). 38 Robert Cox, "Production and Security," in David Dewitt, David Haglund and John Kirton, eds., Building a New Global Order Emerging Trends in International Security (Toronto: Oxford University Press, 1993). 39 An interesting example could be found in the Asia Pacific human rights NGO gathering in Bangkok prior to the UN Conference on Human Rights in Vienna in 1993. There, the NGO community produced two drafts of a final declaration. The initial draft, containing the'views of Western NGOs, was contested by Chandra Muzzafar, a leading Malaysian human rights scholar and activist, who felt compelled to rlic?r;re.. ?!it!? !!?o Wes!e:: ?!GC?pe:spec:i~;a on whai sP,oulu" be h i i e . Ethnocentrism and Emancipatory IR Theory 17 Thus, to say that culture matters in explaining international relations adds to our perspective only if one compares it with the unbelievable lightness of rationalist Western IR theory. Against this backdrop, the return of culture and identity should be happy news to those fighting ethnocentrism in IR. After all, questions about culture necessarily call for a recognition of a diversity of experiences and encounters in the world in which we live. Getting one's identity recognized could mean breaking out of the margins. Yet, such celebrations may lead us in directions that may result in oppression and further marginalization. The emancipatory claims of culture and identity approaches deserve closer scrutiny. Theories that accept culture and identity as legitimate points of discourse are of a broad variety: state-centric, society-centric, and post-structuralist. Not all culture-based explanations of IR look to society for their explanatory power. Wendt, a constructivist, and Katzenstein, a cultural institutionalist, remain wedded to a state-centric project. For them, bringing in issues of culture and identity has meant exploring the identity of the state. The emancipatory potential of culturelidentity discourses lies in the recognition of the margin, the representation of the object, and the empowerment of the weak. But here post-structuralist perspectives on culture and identity do not entirely overcome the problem of ethnocentrism. David Campbell's influential and popular work explains the foreign policy of the U.S. as an identity-inscribing process, but as Rodney Loeppky points out, it is "ill-equipped to ascertain certain unique aspects of identityformation in states subjected to the foreign policy of an outside power such as the United States."40 The dynamic of identity formation among Western actors is different from that among non-Western actors because in the case of the latter, the identity of states - in everything from its citizens to its political structure - may be partly an effect of outside penetration. "Under such a process, the identity of the 'other' is formulated in a manner which reaffirms, and often strictly reinforces, the dominant selflother environment within which it operates."41 While Campbell assumes that the American state can have an unlimited capacity to enact politically "useful" policies in its identity-generating historical processes, it is hard to accept that this sort of capacity could exist in the Third World. Ironically, therefore, Campbell's work can do with a little dose of Ayoob-like effort to differentiate between the West and non-West, including the differences in state capacity and the very specific socio-political cohesion of the latter. 40 Rodney Loeppky, "Identity Analysis and Non-Western Foreign Policies," unpublished paper, York University, Department of Political Science, Fall 1997, p.1. 41 /bid.. p.6. 18 Acharya There can be no safe assumption that a cultural approach is emancipatory, or that to ask questions about identity involves more than fighting the narrow positivist bias of neo-realism and neo-liberalism. Culture and identity are not categories that always lend themselves to emancipatory projects. Culture is inherently boundary-minded, and identity easily fits into a project of exclusion. This happens not only in the hands of states, but also in those of social movements and of various other representatives of the margins. One example of the negation of universality by arguments from a cultural standpoint is easily found in the universalist-relativist clash over human rights. Governments in Asia today question the universality of human rights and consider the Universal Declaration on Human Rights as an instrument created by the West reflecting its own particular values and identity. But this may be a call by authoritarian rulers invoking culture to survive in office. Moreover, one should be mindful of the use of culture and identity by Western governments and analysts in dealing with the so-called 'ethnic conflicts' in the Third World. Here, culture provides a ready-made and relatively unproblematic framework for analyzing violence in the Third World, as something of an ahistoric and 'inevitable' phenomenon. Focusing on culture and identity means shifting attention away from other, possibly more salient causes of ethnic warfare, including issues of socioeconomic development, marginalization, and North-South inequities for which blame must be shared by both the West and the non-West.4' Conclusion In their well-known, if dated, survey of the field, William Olson and Nicholas Onuf hoped to see "the ideal of a cosmopolitan discipline in which adepts from many cultures enrich the discourse of International Relations with all the world's ways of seeing and knowing." But they also warned that globalization of IR may well indicate "the successful diffusion of the Anglo-American cognitive style and professional stance rather than the absorption of alien modes of thought."43 This is exactly what has happened and continues to be the problem. The belated and ongoing efforts by the community of IR scholars to 'globalize' their discipline have merely entailed the drafting of more Third World scholars into the field that continues to be defined and dominated by Western categories and concepts. This chapter has sought to highlight the need for some urgency in addressing the problem and to render the discipline truly universal by recognizing and incorporating the ideas and the experiences of the non-West. Ethnocentrism is one of the most pernicious forms of exclusion in IR theory. It is also one of the foremost challenges for the emancipatory project, with which the field has yet to fully come to terms. 42 Matina Karvellas, "International Relations and Inter-Discipline: Redefinition without Recourse" unpublished paper, York University, Department of Political Science, Fall 1997, pp.7-8. 4 1 Olson and Onuf, op. cit., p.18.