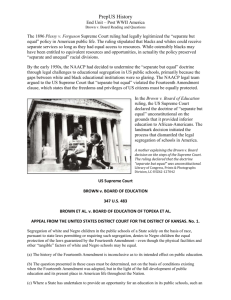

THE STATE ACTION DOCTRINE AND THE PRINCIPLE OF

advertisement