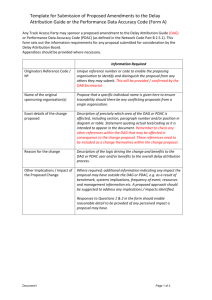

Defense Acquisition Guidebook - National Defense Industrial

advertisement